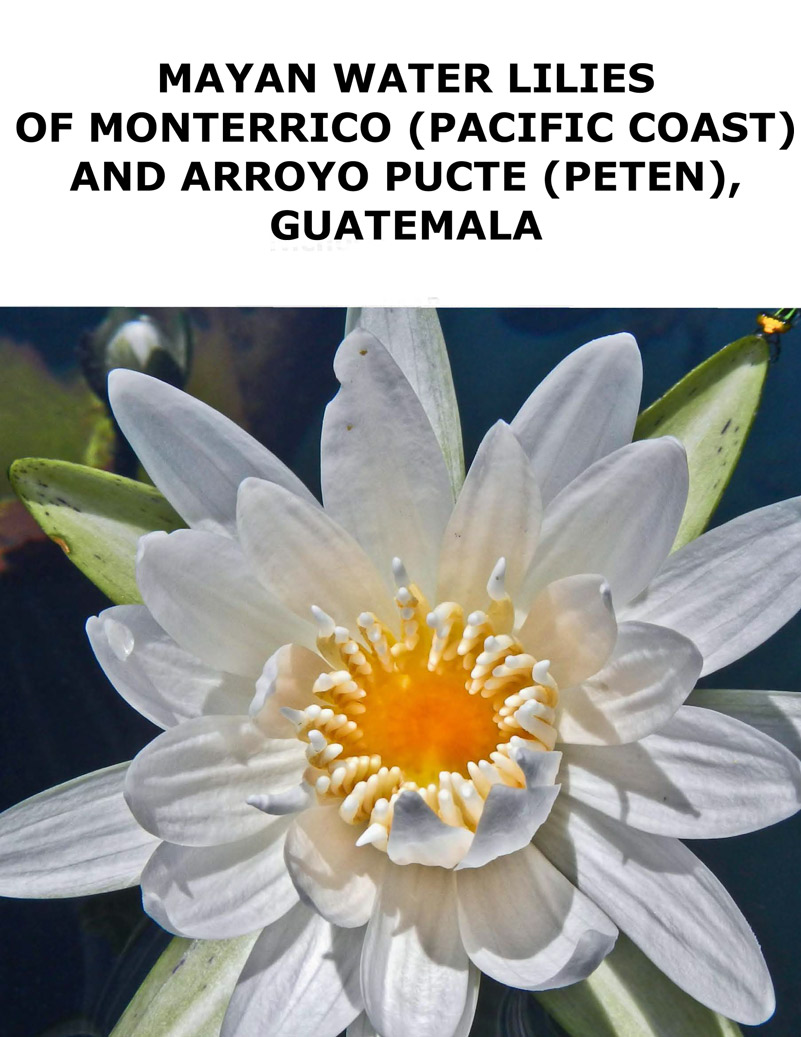

The Chiquimulilla canal, a canal created by the local towns-people of the Pacific Coast of Guatemala, became a beautiful mix of ecosystems over the course of one hundred years! Any canal is defined as an artificial waterway that is constructed to allow the passing of boats, or to change its path in order to use it for anthropogenic activities such as agriculture. The Chiquimulilla canal isn’t any different from others in terms of its definition; what makes this canal so special is its history and the beautiful biodiversity that was collected over the passing of time, including the formation of intriguing mangrove forests.

A canal created by local merchants that became a mangrove forest with singular biodiversity

During the early 1800s, merchants all over the Guatemalan Pacific Coast struggled to make commerce with nearby towns and cities. Back then, a limited number of roads could be traveled by merchants, and the motor vehicles we know and use today wouldn’t arrive until almost a century later to the region. This resulted in a lot of food and produce being wasted, or in the loss of the farmers’ hard work and livelihood. According to the author Eduardo Pineda Pivaral, who tells this story in his first-person monograph, it was Chiquimulilla’s Major Lázaro Sales who encouraged all the merchants from the region to help build a canal that merged the several ditches that already existed near the Puerto de San José (which was Guatemala’s main pacific port at the time). Motivated by the possibility of commerce between several towns and cities, men and women from all over the region gathered with hoes, machetes and axes to start building the canal on a beautiful morning of January, 1886.

The exhaustive construction work lasted months, and people would put up camps to spend the night and then continue working in the morning. As one can imagine, the life-threatening aspects of this feat were several, including mosquito transmitted disease; poisonous and carnivorous wild-life; and muddy, quicksand-like areas. Families helped from a distance as well, sending natural and ethnobotanical remedies for disease like malaria or food-poisoning, snake-bites and severe sunburn. After a while, this work was noticed by politicians all over the country, who began contributing with permits, remedies and resources to the creation of the canal alongside the local people. This canal is still one of the main sources of income for many Guatemalan families, due to different activities like tourism, fishing, research and agriculture. It connects several cities and towns across the Departments of Jutiapa, Santa Rosa and Escuintla, and it has gathered a very interesting biodiversity and ecological importance.

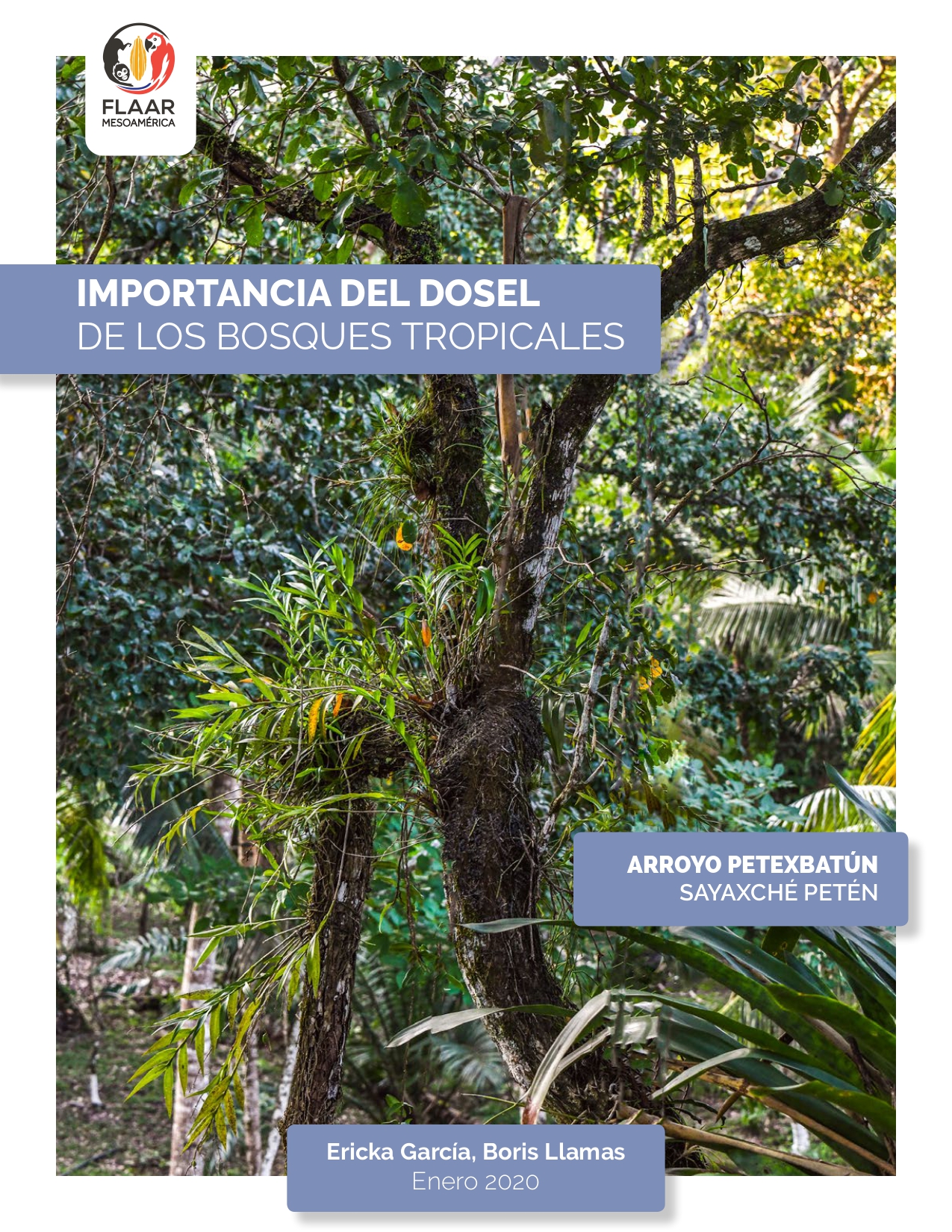

Biodiversity of the Mangle forest

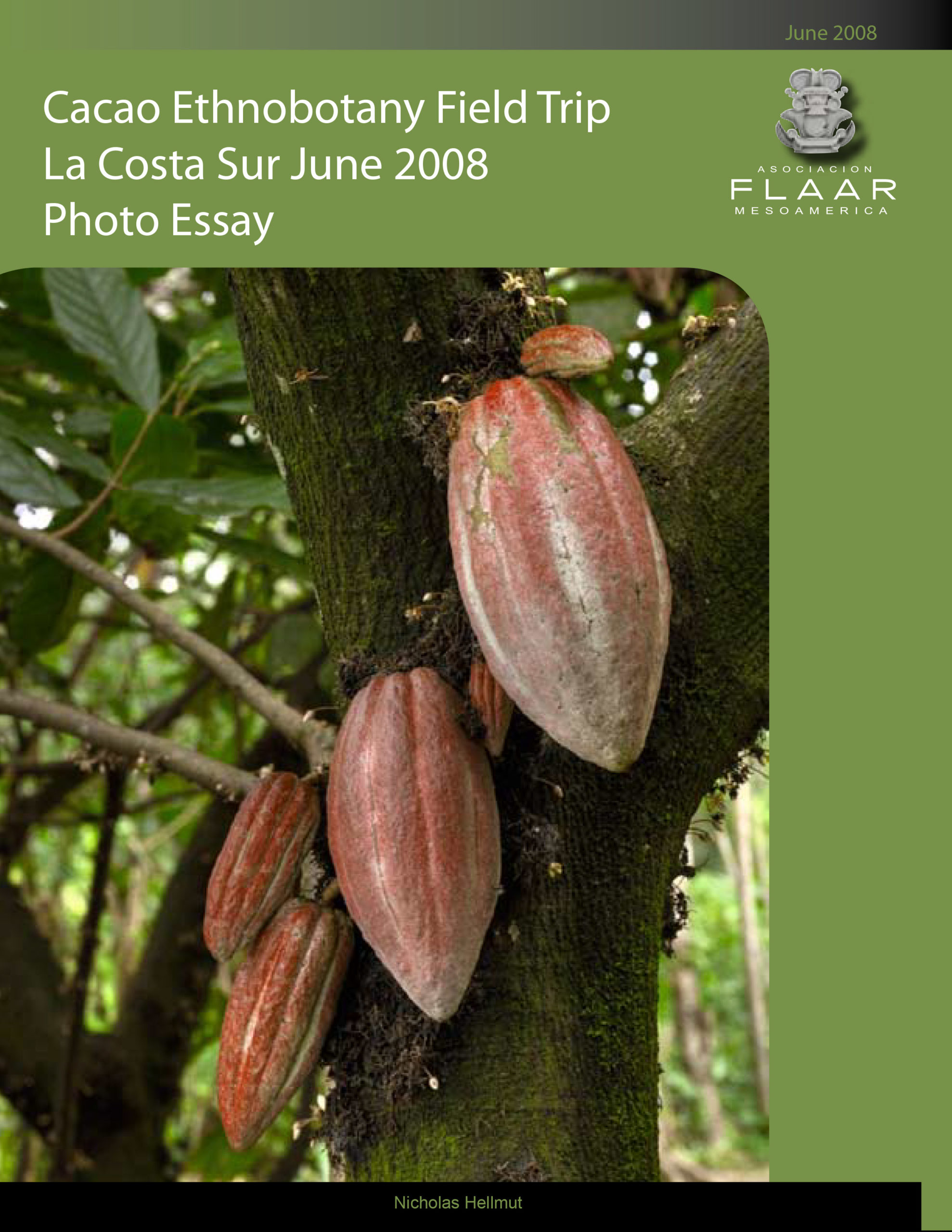

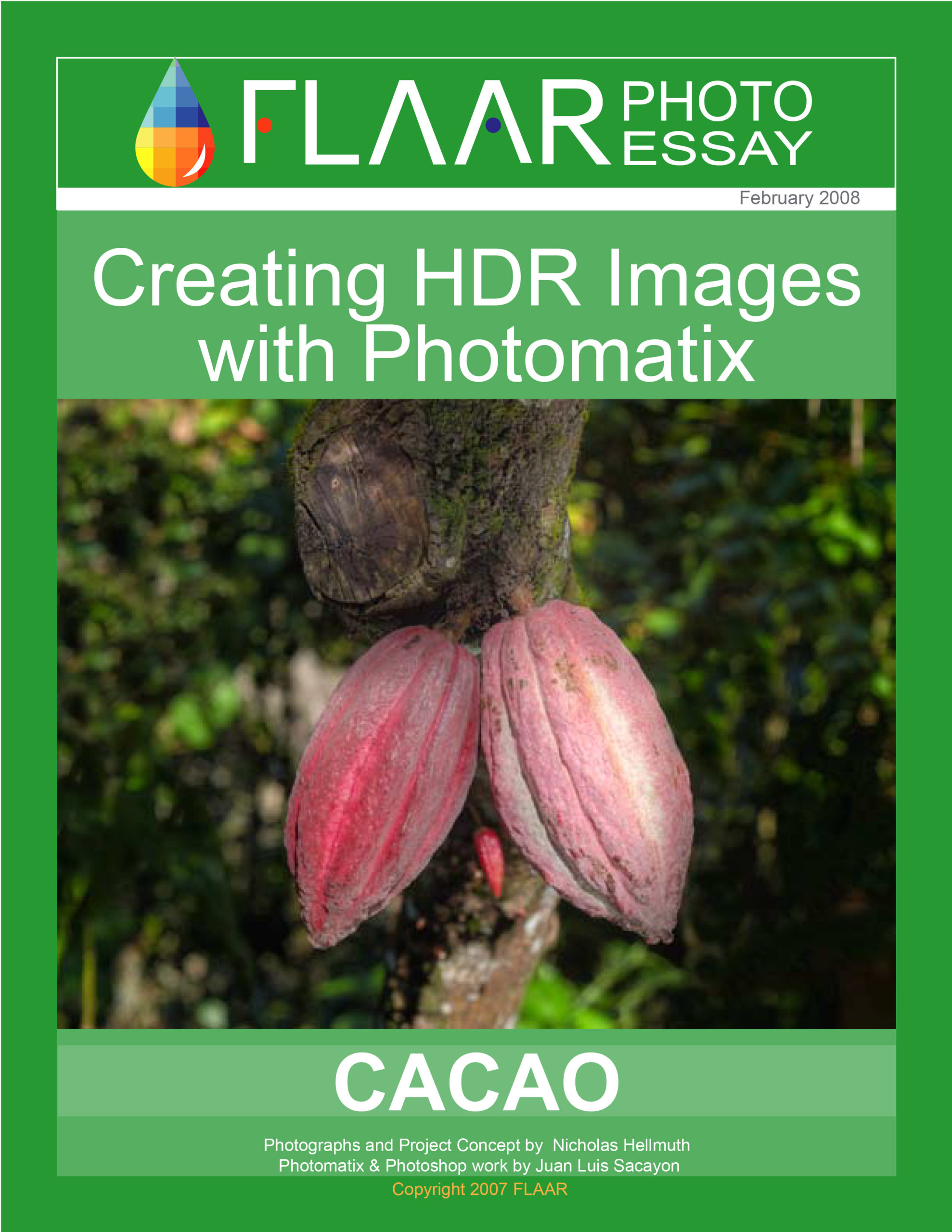

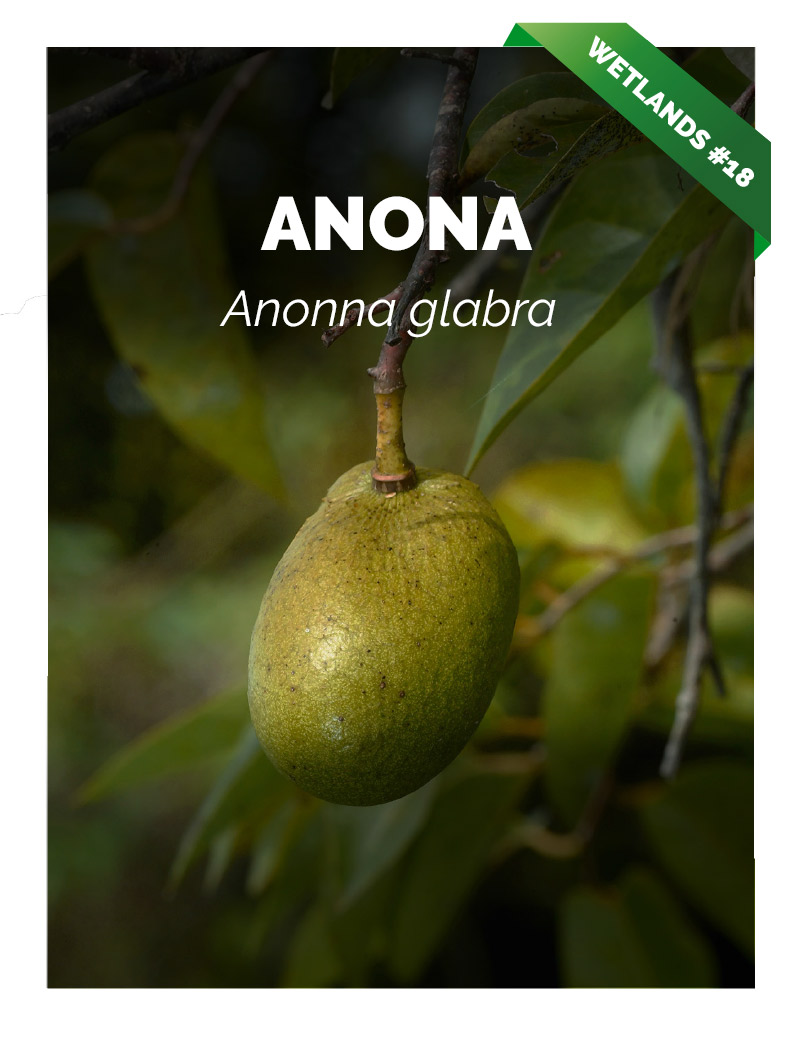

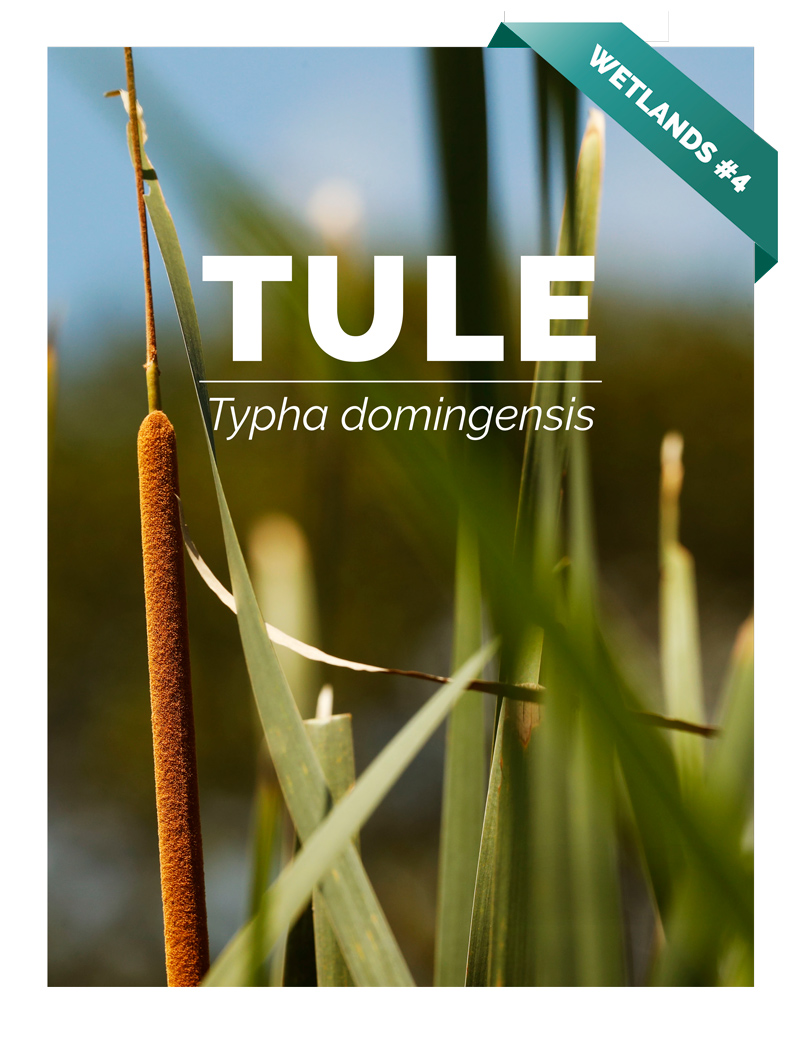

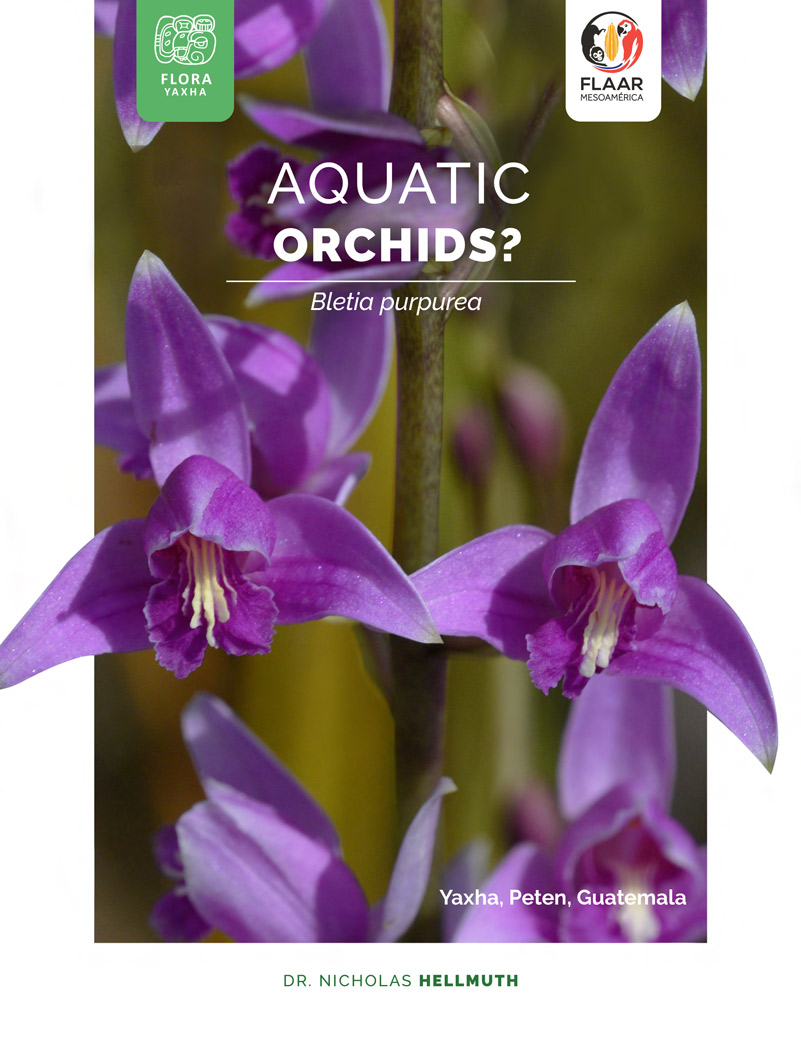

Over the years, the Chiquimulilla Canal has formed a mixture of ecosystems that are home to dozens of different species, including the stellar species of this post, the Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Reptiles and mammals are often found; in fact, beautiful species of sea turtles, like the Parlamas (Lepidochelys olivacea) and the green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), use these shores as nesting areas. In fact, there is a part of the canal which is its own estuarine canal called La Poza del Nance, that is a very important feeding zone for several species of turtles. Many studies and efforts are being focused on this area due to its importance to the overall canal's biodiversity.

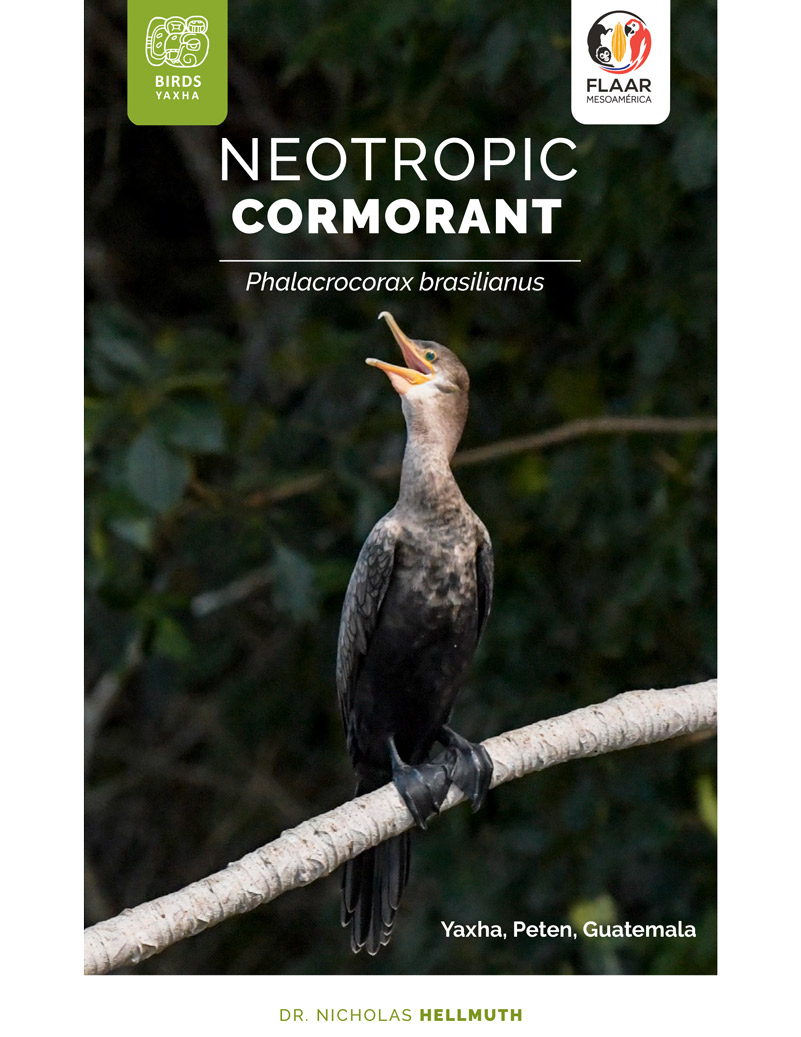

Also, over fifty reported species of fish can be found throughout the canal, not to mention crustaceans and molluscs who share these spaces with them. These ecosystems have also become vital for the routes of several species of migrant birds such as the white pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) and the scissor-tailed flycatcher (Tyrannus forficatus). In addition to being the home of these native, endangered or community-forming species, the mangrove forest also represents a protective boundary against storms and flooding; it prevents erosion, and it aids in the absorption of carbon dioxide and production of oxygen released to the atmosphere. The existence of ecosystems like these hold the life and well-being of hundreds of species, including fish, birds, mammals, reptiles, crustaceans, plants, fungi, and of course, us humans.

Photography by: Victor Mendoza, FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 16, 2021. Canal de Chiquimulilla, Guatemala.

Nevertheless, blinded by greed to the natural beauty of the canal, a fast and boundless agricultural and stock farming development has already destroyed many of these ecosystems and has threatened many of its species. As of today, the only remaining forests with significant coverage are the Red Mangrove forests of the coasts, and even these are facing several adverse conditions. Chiquimulilla Canal's mangrove forests are currently under a series of threats, including unregulated deforestation, pollution, climate change, wildfires and, as mentioned before, the presence of different types of farming. In spite of being part of Guatemala’s Protected Areas since 1999, and the many conservational efforts that have been made over the years, currently the massive expansion of industrial sugarcane production in the area is the main concern to its integrity as an ecosystem.

Mangrove forest ecosystems have been proven to be highly productive and resilient, but they aren't indestructible and need careful conservational management. The preservation of these ecosystems is necessary in all the possible levels. Conservation efforts can have many faces and no effort is too small. From ecologically conscious tourism, to studying and documenting the flora and fauna of the region; working with the neighboring communities in order to inform and conscientize; studying the ecology of the remaining forests to elaborate better conservational programs; or the passing and respecting of the laws that seek to preserve the natural integrity of the canal's ecosystems; all efforts, tiny and huge, are called for.

Understanding and respecting these ecosystems’ importance is already a big first step, and in FLAAR we hope that this article can help the interested minds to take that initial stride. Our main goal in FLAAR is to use research and high-quality photographs as our contribution to the World’s Knowledge about Mesoamerica’s rich and complex biodiversity, cultural heritage and ancient wisdom. Hidden in the middle of wetlands, jungles, savannas and hundreds of mixed and singular ecosystems, we have been able to capture this native beauty through the lens. We wish to show this history and these sceneries to all of those who may be as perplexed as we are, as well as for the future researchers and avid conservationists who may be looking for a paradise just like this to care for, study and protect.

Photography by: María Alejandra Gutiérrez, FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 16, 2021. Chiquimulilla Canal, Guatemala.

Photography by: Victor Mendoza, FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 2021. Chiquimulilla Canal, Guatemala.

Photography by: FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 16, 2021. Chiquimulilla Canal, Guatemala.

Photography by: FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 16, 2021. Chiquimulilla Canal, Guatemala.

Photography by: María Alejandra Gutiérrez, FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 16, 2021. Chiquimulilla Canal, Guatemala.

Photography by: Nicholas Hellmuth, FLAAR Mesoamerica, Jan. 16, 2021. Mangrove Forest, Chiquimulilla Canal, Guatemala.

Cited References:

- 2022

- Canal de Chiquimulilla en Guatemala. Notas Para Aprender Sobre Guatemala - Guatemala.com.

Available online: https://aprende.guatemala.com/historia/geografia/c

anal-de-chiquimulilla-enguatemala/#:~:text=Origen%20de%20su%

,iniciativa%20de%20hacer%20ese%20paso

- 1999

- Acciones curriculares de las escuelas primarias del municipio de Taxisco, Santa Rosa, en relación al deterioro del bosque manglar. Thesis- USAC. 24 pages.

- 2011

- Diagnóstico del Estado Actual del Recurso Manglar y Consumo Familiar de Mangle en el Área de Usos Múltiples Hawaii, Chiquimulilla, Santa Rosa, Guatemala. ARCAS (Asociación Rescate y Conservación de Vida Silvestre) with the financial support of the FAO-PFN-INAB. Chiquimulilla, Santa Rosa, Guatemala.

- 1969

- Monografía Santa Cruz, Canal de Chiquimulilla. Editorial Tipografía Nacional. 502 pages.

Posted March 7, 2023

Written by Alejandra Valenzuela