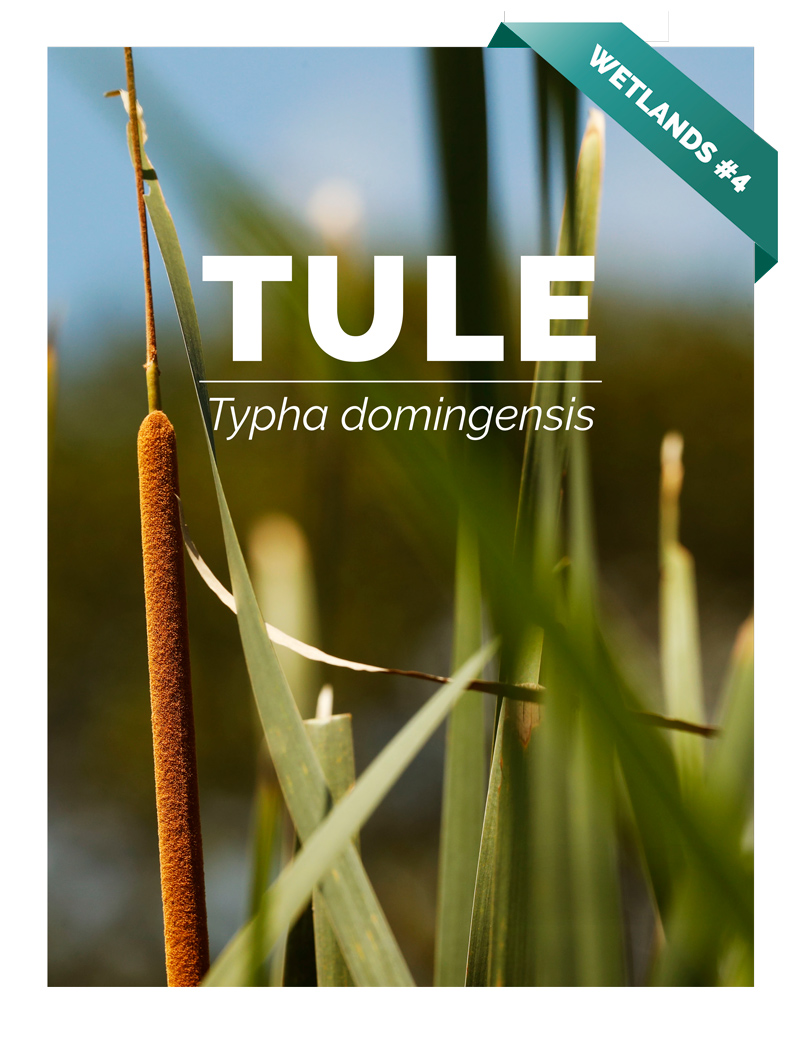

Dual Projects: Study of all trees of Bombacaceae family & study of natural beauty of flowers of plants used for traditional Maya smoking

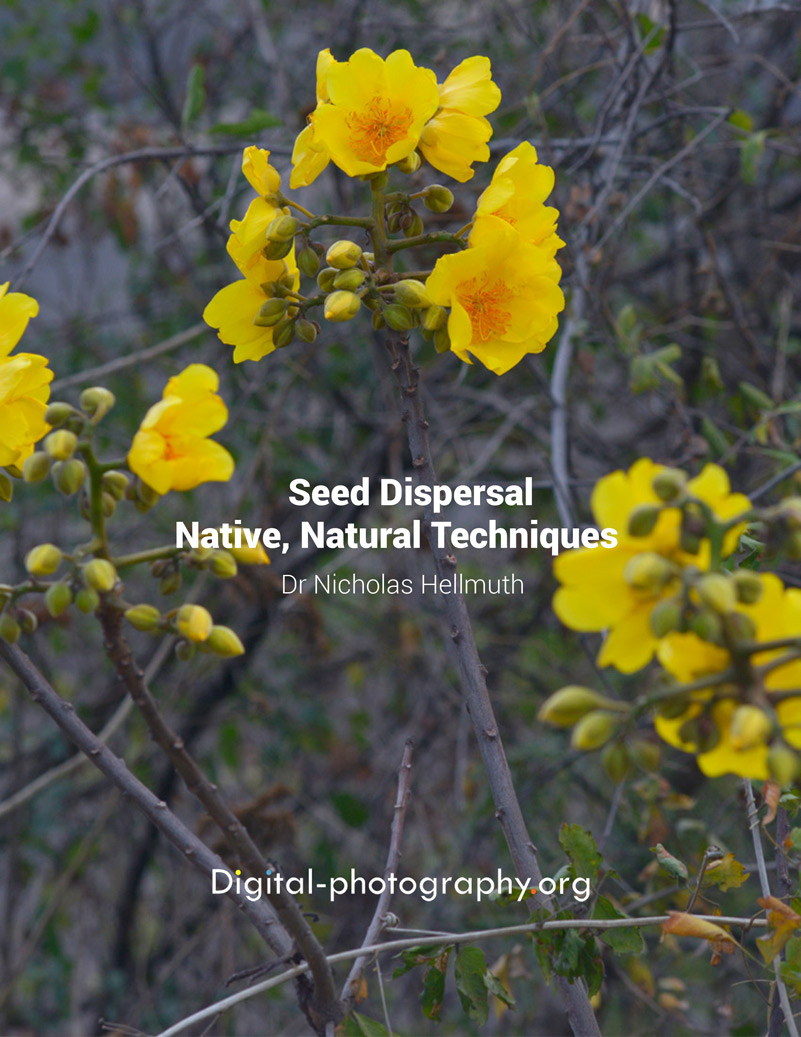

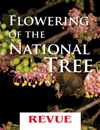

Since the giant Ceiba pentandra tree is the national tree of Guatemala today, and was the primary “World Tree” of the Maya and Aztec a thousand years ago, I have become interested in learning about all other tree species related to the family Bombacaceae. Bernoullia flammea is a member of this family with unusual flowers.

It took three years to locate the tree (because we are looking for a total of 400 Maya-related trees and plants). Now we know precisely there all the best examples are: many in Tikal and two outstanding specimens two hours drive south.

During the process of studying Bernoullia flammea tree I learned that the seeds may be edible. One other web site suggests that two known and respected ethnobotanists, Rob Montgomery and anthropologist Brett Blosser had stated “The seeds are smoked by the Guatemalan people living in the area around the spectacular Mayan ruins of Tikal.” Since this tree has remarkable orange-red flowers I began to do more research because I am curious what plants the Maya smoked, what plants the Maya used to flavor their incense (which is also smoke). And I have discovered that some of the same plants that were smoked were used as spices or condiments for beverages or food.

The comments by Montgomery and Blosser were important because no botanical article or monograph lists Bernoullia flammea as being smoked (but over 50% of the other plants on my list of plants which the Maya smoked are probably missing from most monographs on smoking, and definitely missing from most books on Maya agriculture.

Local Name(s) for Bernoullia flammea Olivier

Locally in El Peten the tree called Amapola blanca (many trees have this name in Mesoamerica, including Pseudobombax ellipticum); also spelled mapola. Although Bernoullia flammea is a relative of the Ceiba of Guatemala, there are no spines whatsoever on the trunk of Bernoullia flammea.

Botanists also list ala de cucaracha, but this name is not widely used in El Peten.

You can expect additional names in K’ekchi, Yucatec Maya, Lacandon Maya, and potentially in Mopan. The tree is unexpected in the Highlands, but does grow on the other side of the volcanic chain across central Guatemala, in the Costa Sur (whose original pre-Columbian languages have mostly not survived).

We aspire to have funding for an organized linguistic list of each tree for each language. In the meantime we can report: Cante, pojote and Uacut.

Itza: chunté

Itza: aj chäk ch’ulte’ (Atran et al. 2004:191)

Yucatec Maya: wakut, uacut

“Chiapas” (does not specify which language, Chol or Lacandon?): cosanté (:24) But turns out it is Tzeltal (Pagaza and Fernández 2004:77) but from the zona Lacandona. It is unclear whether this is Tzeltal awareness of Lowland trees, or a word in the Lacandon Maya language (Lacandon is a close relative of Yucatec Maya and thus also a relative of the Itza language).

It would be helpful to track down the Mopan, Chol, and Chorti Mayan words for this tree.

Major botanical monographs, as recent as 2008, still clearly list Bernoullia flammea as a member of the family Bombacaceae (Parker 2008:100). I am fully aware of the changes in the last several years to rearrange the placement under the family Malvacea.

But the flower, to a lay person, is not similar in size, shape, or color whatsoever to any tree of the under the family Malvaceae or really even the Bombacaceae (now subfamily Bombacoideae since Bombacaceae has been put under the family Malvaceae).

Our interest is to find the trees when they flower and provide to botanists really high resolution photos of the flowers, plus to alert botanists for where they can easily find this tree. It took me several years to find the flowering examples in El Chal, for example. But now we can help botanists by letting them know precisely where the trees are situated.

Why is this tree called amapola?

In the Spanish language, especially in Latin America, a word in Spanish can have multiple meanings. A single word can refer to several completely different trees:

- Pochote: Pseudobombax ellipticum and several other trees.

- Palo de lagarto: many trees with rough bark or crocodile-like spines.

- Amapola: Bernoullia flammea, Tabebuia rosea, Pachira aquatica, and Pseudobombax ellipticum (http://ucr.ucr.edu).

You also notice that any single tree can have several conflicting common names (depends on who you ask, what area of the country, what is the local language, etc).

Plus, not every book or web site is aware of all the names. The UCR.edu web site is very helpful but has zero trees listed under “pochote” which is one of the more common names in several areas of Guatemala for different trees. Since I have lived in Guatemala for decades and as I am out in the field at least every six weeks, I have plenty of discussions with local people in Peten, Izabal, and Alta Verapaz, plus the Costa Sur.

That web site also did not reveal a single tree with the name “lagarto” yet this is not only a common name in Guatemala, it is also crucial for understanding the Crocodile Trees of Izapa stelae (Chiapas) and Early Classic ceramic art (which I discuss in my PhD dissertation). Nonetheless that web site , Árboles Tropicales Comunes del Area Maya:, is helpful in other aspects.

Bernoullia flammea is not listed by Wilson in his PhD on ethnobotany of the K’ekchi.

This 1972 dissertation does not include Bernoullia flammea. Parker does not list Alta Verapaz either. But considering the range of Bernoullia flammea in Mexico, I would expect Bernoullia flammea at least somewhere in Alta Verapaz. This question is mainly in the interest of finding the K’ekchi Mayan word for this tree.

Otherwise we have primarily the Yucatec Maya and Itza (Yucatec Maya in Peten).

Locations for where to find Bernoullia flammea

This tree is best known from Peten, Guatemala, but is also found in the Costa Sur of Guatemala. So clearly the tree prefers seasonally rainy climate. Bernoullia flammea is also found in Mexico, including in the Rio de las Balsas drainage (Pagaza and Fernández 2004) and in Jalisco, Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Veracruz. Surprisingly they suggest it can grow in a habitat of an altitude up to 1500 meters (Ibid:78). If you spend several hours looking at technical botanical reports by UNAM you learn that the tree is also found in Colima Padilla et al. 2006:282). So today the range is significantly better known than in the years of Standley and Steyermark (1940’s and 1950’s).

Although not expected in the Central Mexican home of the Teotihuacan, Toltec or Aztec, they had trading routes to every State of Mexico where the tree does occur. These imperial courts could afford to bring in whatever plant product from anywhere in Mesoamerica.

Phenology, Flowering time for Bernoullia flammea

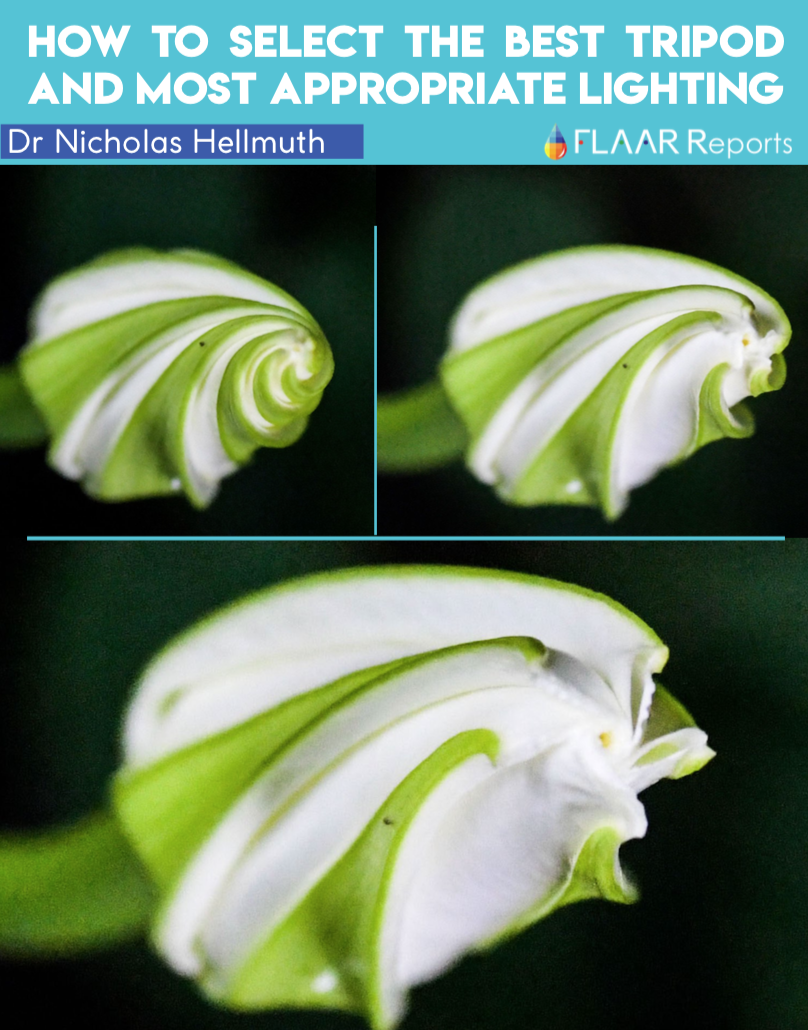

The first time I noticed this tree flowering in recent years was the during spring, 2012. I saw one tree near Temple III and another near Temple I of Tikal. The tree near Temple III was so high that until we have funding for a 600mm prime lens it is not realistic to attempt to get photos of the flowers from the ground. But we took snapshots of a few of the fallen flowers on the ground. Only later, when I was back in my office (a long way from the tree in Tikal!), did I realize these were flowers of a member of the Bombacaceae family.

So we waited an e ntire year until we estimated the tree was flowering again, and made the one-week round trip field trip to photograph all the Bernoullia flammea in the central part of Tikal. Except for two trees they were all either too high or too far away even for a 400mm lens. A 600mm lens is just under $13,000, but this is the only way to achieve professional quality photos of a flower this high up in a tall tree. A tele-extender helps (with a 400mm lens) but our 100-400 tele-zoom together with a 1.4x tele-extender can be beaten by the quality of a 600mm Canon prime lens. We are familiar with Sigma lenses; Canon is generally regarded as better.

Flowering time will be different in each country, and even in different parts of the country. But we did notice that in Peten, in mid-March, every Bernoullia flammea tree was in full flower. But only in one area were there seed pods. For a Bombacaceae it can take up to several months for a seed pod to mature and open.

Seed pod vaguely reminds me of pods of Ceiba and Pseudobombax

Only the seed pod is vaguely reminiscent of other genera from the Bombacaceae.

I saw no silk in the pods; the seeds are winged, in rows. Each seed overlaps its neighbor below. None of the trees at Tikal had noticeable pods whatsoever. But the group of two trees along the highway near El Chal had lots of pods (in the tree and already fallen to the ground). The seeds are obviously intended to drop (like half-helicopters) from above, but one of the pods still had at least five seeds.

The seed pods are significantly wider and more than twice the length of any ceiba pod. Normally we dedicate time to study the entire sequence of growth: from bud to flower to green seed to final seed. But these trees are so tall that we can’t photograph any of this. Only one tree at Tikal can you touch the flowers (without a ladder). Another you can see straight in front if you climb the back of Maler’s Palace.

On the last day we did find a branch of another tree (in the Central Acropolis) where you could study the sequence of flowering, but I estimate you would need to be there weeks to experience (and record) the full sequence. All the other trees are the equivalent of 4 stories tall (a ceiba tree can be over 10 stories tall; some are much higher).

Since there were no noticeable fruits anywhere at Tikal, it would be worthwhile for a botanist to visit the grove of Bernoullia flammea near El Chal, El Peten (perhaps 45 minutes before Machaquila-Poptun area), on the east side of the main paved highway, a hundred meters before the town of El Chal starts.

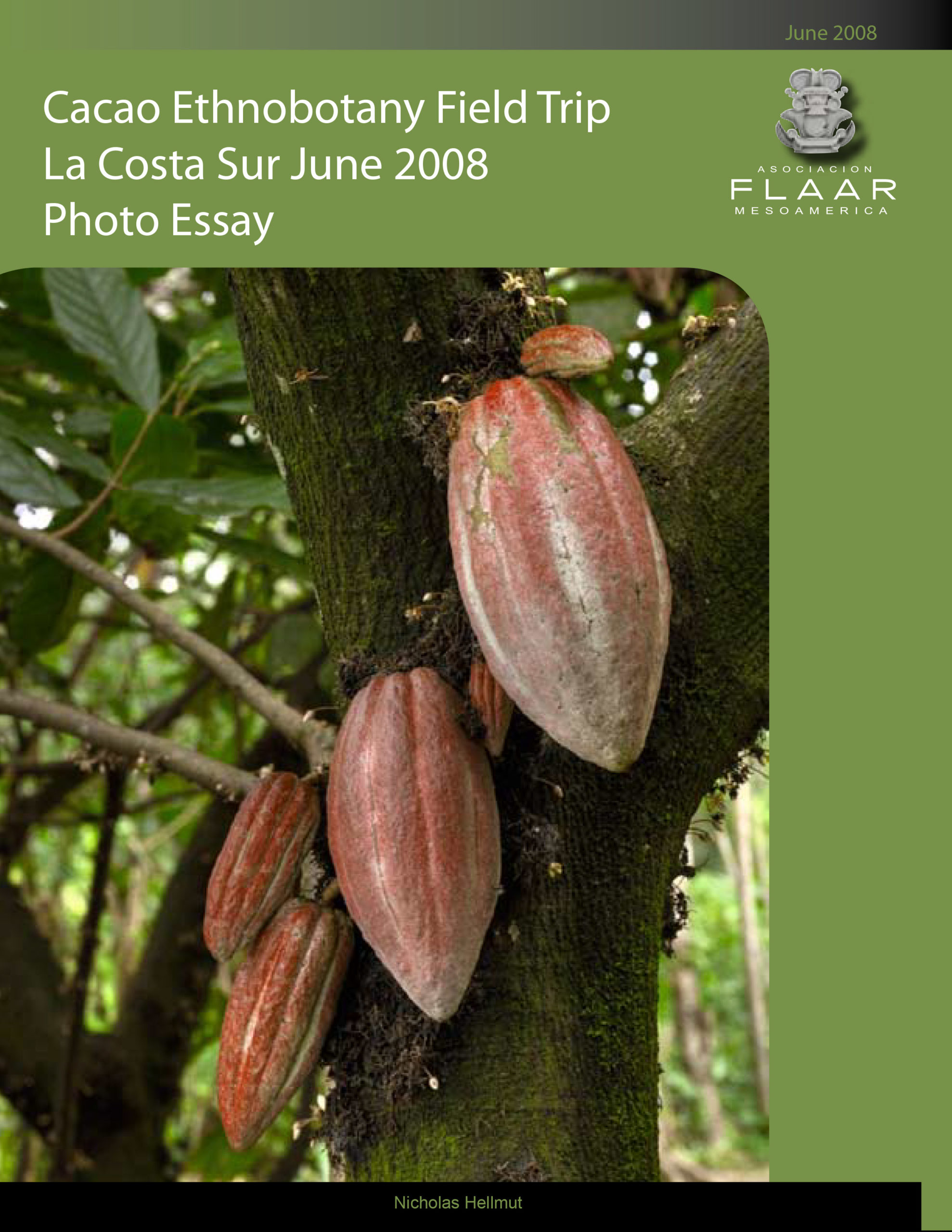

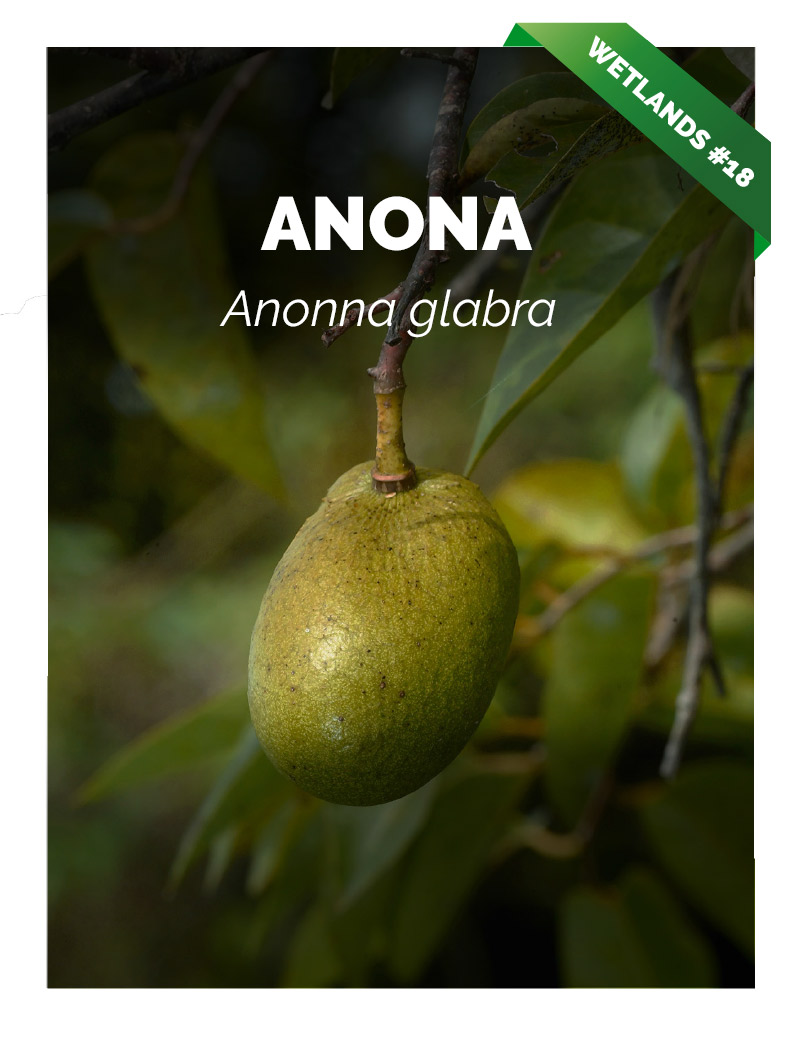

Fruit is almost pseudo-cacao size, even with flutes

Fruits and seeds of tropical trees of Mexico are nicely listed in the moography specifically on this topic (seeds and fruits) by Rodriguez et al (2009:24). There is no information given on use whatsoever. He indicates the pods can be up to 30 cm long. The three pods I measured from near El Chal, El Peten were:

- 21 cm for one.

- 19.7 cm for another.

- 19.2 cm for another.

All three we collected from the ground, with the permission of the property owner.

I am speaking of the aldea of El Chal: not the archaeological site. I have never been to that site. We do our research primarily alongside highways. This way we can cover more eco-systems.

The person who owns the property on which the trees are located has a store across the street from the gas station. There is a worker’s house near the two trees. The people were helpful to allow us to visit their property and do the photography. It was dusk and we had a long way to drive that evening.

Observations by botanists (Standley et al.) on Bernoullia flammea

Bernoullia flammea Oliver. Mapola. Collected at several localities; Oaxaca to Guatemala and Honduras. A large tree as much as 30 meters high, with a trunk 90 cm. in diameter; leaflets 5-6, oblong-oblanceolate, 10-22 cm. long, acuminate, glabrous; inflorescence bright fire-red; calyx 1 cm. long; petals recurved; stamen tube long-exserted; fruit brown, ellipsoid, woody, 20 cm. long. (Standley and Record 1936:248, Vol XII.

The following is from Flora of Guaemala, Vol. 24, Part VI:

BERNOULLIA Oliver

Large trees, almost glabrous but with sparse pubescence of small stellate hairs; leaves long-petiolate, digitately compound, the leaflets membranaceous, petiolulate, entire; flowers small for the family, in many-flowered cymes, second upon the branches, pedicellate; calyx campanulate, shortly 5-lobate, the lobes deltoid, valvate in bud; petals 5, adnate to the stamen tube, oblong, longer than the calyx, longitudinally veined, revolute at the apex; stamen column exserted, laterally cleft almost to the middle, antheriferous at the apex; anthers 15-20, sessile, 2-celled, the cells linear, longitudinally dehiscent; ovary ovoid, glabrous, 5-celled, the cells many-ovulate; style elongate, glabrous; fruit ligneous, oblongellipsoid, acutely 5-angulate, 5-valvate; seeds with a broad thin wing.

The genus probably consists of a single species. Another species described recently from Brazil is suspected to be generically distinct.

Bernoullia flammea Oliver in Hook. Icon. PI. 12: 62. pis. 1169, 1170. 1873. Uacut (Peten); Cante; Ala de cucaracha.

Type collected at Ixtacapa, Suchitepe"quez, Bernoullia 553. Occasional in the rather dry (during the winter months) forest of the higher plains and lower foothills of Retalhuleu (San Felipe and elsewhere) and Suchitepequez; Peten. Oaxaca; British Honduras; Atlantic coast region of Honduras.

A large or medium-sized tree, sometimes 30 meters tall with a trunk a meter in diameter, the bark brown, the trunk tall, the crown somewhat depressed and spreading; leaflets usually 5-6, sometimes only 3, oblong-oblanceolate, 10-22 cm. long, acute or acuminate, cuneate-attenuate to the base, thin, green, almost or quite glabrous; whole inflorescence bright red or orange-red, sparsely puberulent, the flowers long-pedicellate; calyx 1 cm. long, shallowly lobate; petals recurved; stamen tube long-exserted, the anthers clustered at its apex; fruit very hard, attenuate to each end, about 20 cm. long, glabrous within; seeds, including the long wing, about 5 cm. long.

Called "mapola" in British Honduras (a corruption of "amapola"); known in Oaxaca as "palo calabaza" and "palo de perdiz." The wood is described as soft and spongy. We have seen very few individuals of this species. It is said to be common in the vicinity of San Sebastian, Retalhuleu, but we have seen only a few trees apparently planted in the fincas, and of only medium size. The trees are leafless during at least the latter part of the dry season and are said to open their flowers at the beginning of the rainy season. The bright red flowers are very showy. The seeds are stated to be edible. (Standley and Steyermark 1949:387-388).

From what they say I would estimate that they did not in fact actually see a Bernoullia flammea tree flowering. My estimate is because the more correct statement, based on having experienced them blooming now two years in a row, would be

“The trees flower when mostly leafless; the flowering time is at the height of the dry season, March and April. They flower weeks (if not more) before the start of the rainy season.

The flowers vary from greenish orange, to orange red, to deep red, depending on how fresh or how old they are, and which part of the flower you are talking about.”

Concluding remarks on Bernoullia flammea as potentially smoked by the ancient Maya

Most reports on pre-Columbian smoking talk primarily about tobacco. My research is to document that “smoking” involved over a dozen other plants. In other words, smoking was a standard feature of prehispanic culture for thousands of years.

Secondly, the Maya used more than pipes: they also used cigars. The polychrome funerary vase which I discovered in 1965, deep in a royal crypt under pyramid Str. 5D-73 at Tikal, shows a man smoking what looks more like a cigar than a pipe.

Third, the Maya enjoyed smoking. The man with the cigar is very happy.

Fourth: other aspects of our project will document that the Maya also used snuff and logically may have chewed or otherwise ingested tobacco in their mouth. It is also widely assumed that the Classic Maya received tobacco in other manners. When I give lectures on this subject around the world I politely remind the audience that the Maya ingested tobacco in every oriface of their body except their ears!

But what is my primary interest is to show that today, in our modern word, we can get pleasure from experiencing the flowers. Indeed many of these trees can be raised in Florida, California, Italy, Spain, Middle East, and Asia.

Lots of things in life cause cancer; tobacco is not the only cause (I do not smoke myself) but I raise tobacco plants because the flowers are attractive. Plus I prefer to enjoy flowers that are more innovative than geraniums!

Introductory bibliography on Bernoullia flammea

- 2004

- Plants of the Petén Itza’ Maya. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan Memoirs, Number 38. 248 pages.

- 1998

- “Bombacaceae”. Flora de Veracruz, 107. Instituto de Ecología, AC. Xalapa, Ver.

- 2006

- Use forms, management and commercialization of “pochote” Ceiba aesculifolia (H.B. & K.) Britten & Baker f. subsp. parvifolia (Rose) P.E. Gibbs & Semir (Bombacaceae) in the Tehuacán Valley, Central Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, Volume 67, Issue 1, October 2006, Pages 15-35

- 2000

- Flora del Bajio y de regions adyacentes. Fascículo 90.

- 2006

- Riqueza y biogeografía de la flora arbórea del estado de Colima, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 77: 271-295.

- 2001

- La familia Bombacaceae en la Cuenca del Rio Balsas, Mexico. Polibotanica, agosto, num 017, pp 71-102. Institutio Politenico National, Mexico D.F.

- 2009

- Frutos y semillas de Árboles tropicales de Mexico. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat), Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INE-Semarnat). 119 pages.

- 1936

- The Forests and Flora of British Honduras. Publication 350, Botanical Series Vol. XII, Field Museum of Natural History.

- 1949

- Flora of Guatemala.. Fieldiana Botany, Vol. 24, Part VI. Chicago Natural History Museum. 440 pages

- 1972

- A Highland Maya People and their Habitat: The Natural History, Demography and Economy of the K’ekchi’. PhD dissertation, Dept of Geography, University of Oregon. 475 pages.

Has excellent line drawings of each pertinent Bombacaceae.

Available on-line.

Plus there are a dozen technical botanical reports, articles not monographs, especially for Mexican areas outside the Maya core. If you Google Bernoullia flammea you will find enough technical articles to keep you busy for several days.

First posted April 1, 2013.