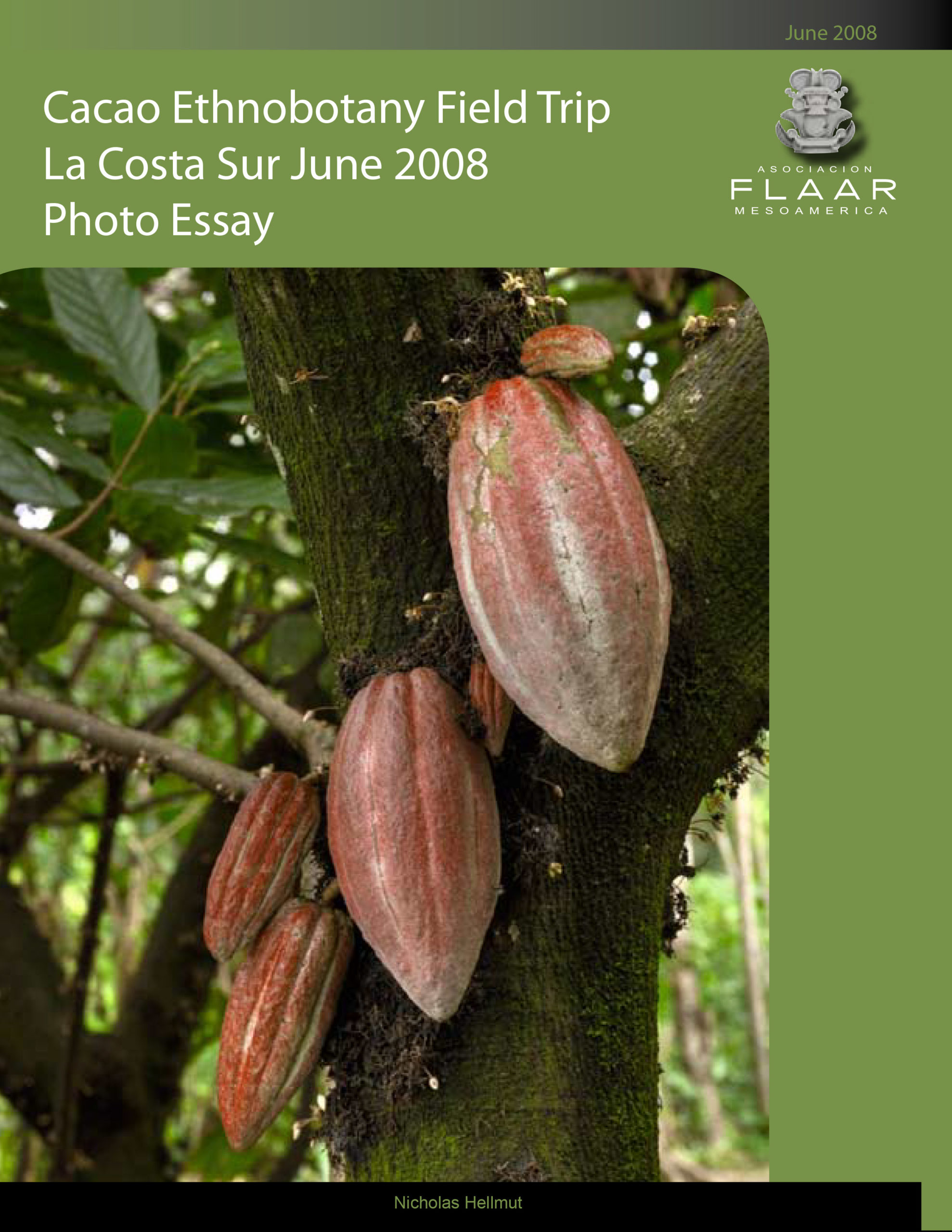

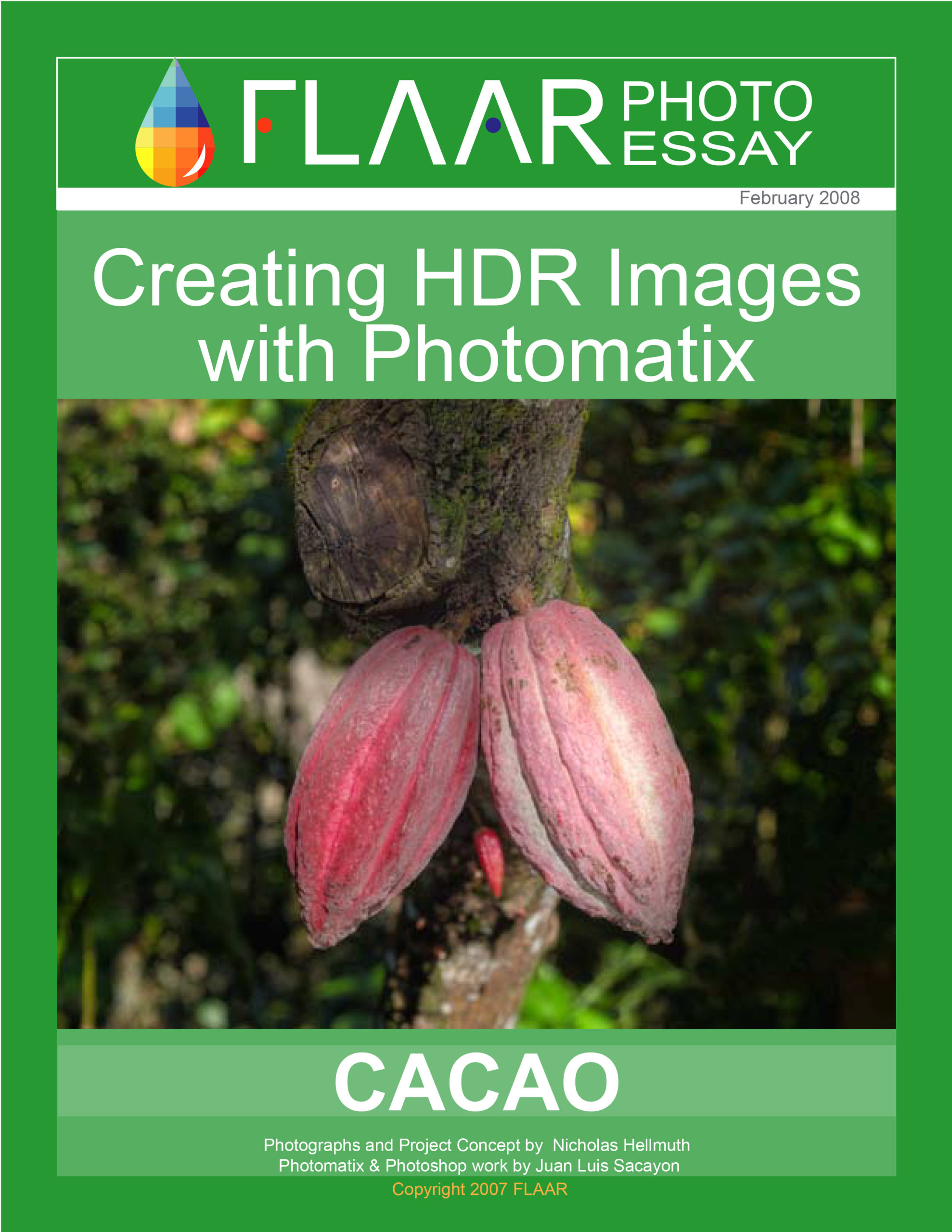

Every year we search for the trees, bushes, and plants whose seeds or flowers or bark was used to flavor pre-Columbian precusor to chocolate a thousand years ago. Some of the flavorings are easy to find:

Achiote is grown throughout Alta Verapaz and Peten. This is an easy to recognize plant and is in every market.

Allspice, pimenta gorda, grows all over El Peten, Alta Verapaz, and Izabal; and elsewhere. Easy to find (though a challenge to locate when flowering). But we finally found a tree flowing at the Parque Nacional Tikal last week.

Marigold is a common garden flower and also used for cemetaries. It was a traditional flavoring for many foods in Maya culture a thousand years ago. Actually it is one of the most commonly used flowers in pre-Columbian spices (even for tobacco).

Cassia grandis, bucut, is everywhere throughout Peten, Izabal, Verapaz and even in dry areas near Guatemala City. Once you recognize what the tree flower and seed pod look like it is easy to find.

Chile chocolate is in most markets of Mayan-speaking villages. Out of the hundreds of varieties of chiles in Mesoamerica, this is the one most commonly used to flavor cacao for the Aztec and Maya.

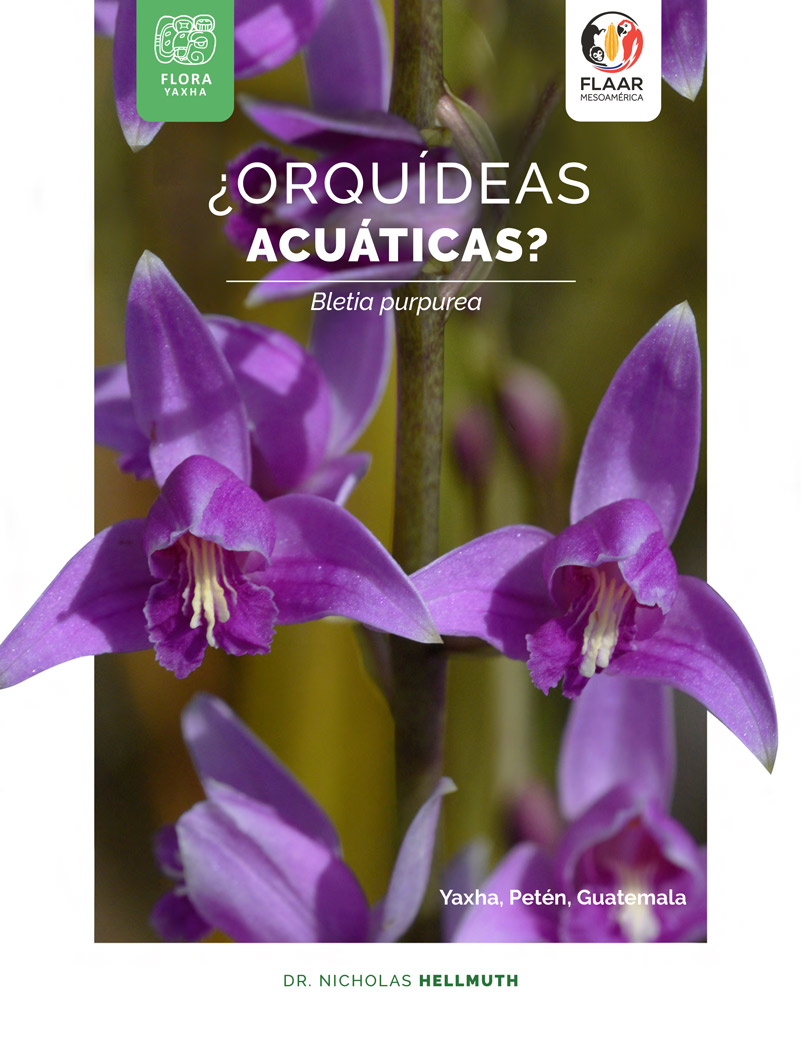

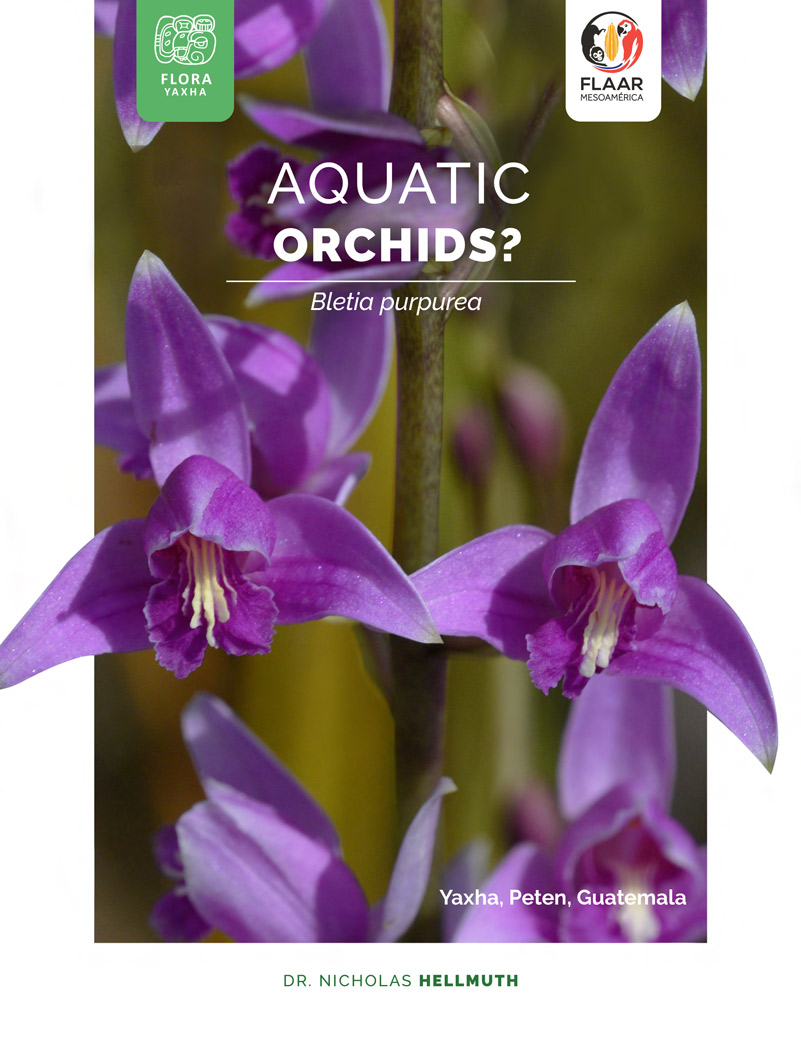

Vanilla is easy to find as a vine, but so far very tough to reach the orchards when they are actually in flower. So we totally lack photos of vanilla orchids in flower. We prefer to do our own photography since we have 21 megabyte and now a 36 megabyte digital camera, professional studio lighting (portable, so we can take it anywhere in Guatemala), and we also have special macro lenses and lighting for macro photography.

Sapote (zapote) seeds are easy to find and are still sold in local markets for flavoring chocolate.

Other flavors for pre-Columbian chocolate we have not yet been able to find:

Clerodendrum ligustrinum, Istim-te, itzimte. No one can tell us anything about this tree. But is is a species clearly listed in all monographs on the botany of Guatemala.

Cymbopetalum penduliflorum, muc, ear flower, orejuela. Last year was common as medicine in many local Mayan markets. This year totally absent from the two main K’ekchi Mayan markets of Coban, Alta Verapaz, and not one person can tell us where to find a tree.

Magnolia mexicana, Talauma mexicana. Not a Lowland plant, so even more difficult to find. Listed as for Huehuetenango. The recent hail storms (early April 2013) probably destroyed most flowering bushes in that Highland area of Guatemala

Smilax species. Sasparilla; have not found this yet in Guatemala. But we will be driving to the Costa Sur to inspect an ethnobotanical finca to see if he has this plant. There are several species of potential interest.

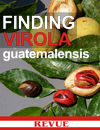

Virola guatemalensis, cacao volador. Nobody could tell us where to find this tree. We found a related species by total accident when we went to study an allspice tree in an orchard. One of our more observent staff members noticed that the fruits of another tree were almost identical to the photos we had on our WANTED list.

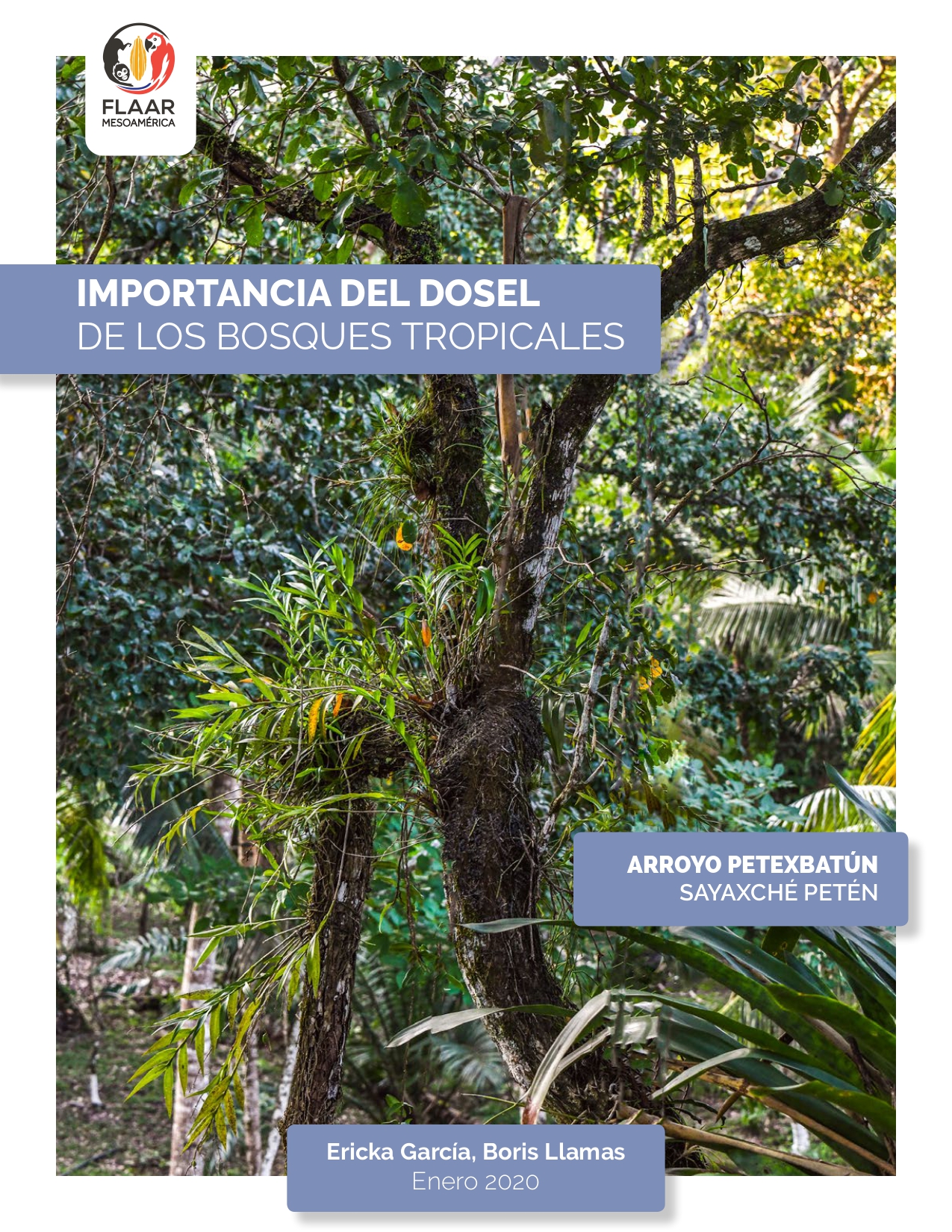

Here are the fruits and leaves (Departamento of Izabal, Guatemala)

A branch of Virola guatemalensis, nutmeg, with fruits and leaves.

Whole and halved fruits of a plant, whether Virola guatemalensis or Myristica fragrans.

These fruits are from a tree growing near Puerto Barrios. Since there are no flowers it is a challenge to figure out whether these are nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) or Virola species.

Virola guatemalensis is an example of a tree which is very difficult to find.

With the help of Dwight Carter, founder of Frutas del Mundo, near Rio Dulce, Izabal, Guatemala, it was possible to visit a friend of his who had a tree with an almost identical fruit to Virola guatemalensis. This other fruit farm was near Puerto Barrios, Izabal.

Although I am not trained as a botanist, I have worked with plants long enough to understand a bit about the basics of classification. So I understand why Pseudobombax ellipticum, Pachira aquatica, and Ceiba aesculifolia are members of related species (formerly Bombacaceae, now sub-family Bombacoideae). You can see the relationship with your own eyes: just look at their flowers and leaves.

Yet Virola guatemalensis and Myristica fragans look (to a lay person) almost identical. The nut inside the fruit has the most remarkable red “claw” clinging all around the surface. It looks like the plant comes from a foreign planet. So it is curious to me why they are totally different species (one is from Asia, the other from Latin America, so they have developed separately for millions of years perhaps. Ironic that they still look almost identical (the leaf of Virola is longer, so I am sure if both were in front of me I could learn how to distinguish them).

Nonetheless it took us about four hours trying to figure out if the fruit and leaves were Virola guatemalensis or Myristica fragrans. The problem is that too many photos on Google are incorrectly labeled (especially when you have an essentially identical fruit yet two totally different species). I estimate this is nutmeg; the biology student felt it was Virola guatemalensis.

But at least I now know what I am seeking, and I really look forward finding a tree and fruit which I can prove is really Virola guatemalensis. The problem was the tree in the orchard this March had no flowers: only lots of fruit. Without the flower we can’t be certain of the name of the tree. The local people were not very familiar with what the full range of names were.

So now we are studying the two similar trees

So now we have the challenge of learning more about the various genera of the “nutmeg family.” On this web page we list the web sites and textbooks which we have used.

It is amazing how little information is available anywhere about Virola guatemalensis, other than a nice summary by Flores. But no mention of the edibility of the tree nor any ethnobotanical comments on the blood red sap.This tree grows well in many parts of Central America and has huge economic potential. But no local person can tell us enough information to facilitate locating the actual Virola guatemalensis.

Comparative tabulation: Virola and Myristica

The following comments are based on the bibliography at the end of this article.

The APG II system, of 2003 (unchanged from the APG system, of 1998), also recognizes this family, and assigns it to the order Magnoliales in the clade magnoliids.

| Myristica fragrans | Virola guatemalensis |

|---|

| Leaves | The Monodora myristica tree can reach a height of 35 m and 2 m in diameter at breast height. It has a clear trunk and branches horizontally. The leaves are alternately arranged and drooping with the leaf blade being elliptical, oblong or broadest towards the apex and tapering to the stalk. They are petiolate and can reach a size of up to 45 x 20 cm. | Tall trees, to 30 meters high, the young branches rusty-tomentulose or gray-puberulent; petioles 5-14mm long; leaf blades oblong or narrowly oblong, coriaceous or fairly thing, 13-15cm long, 4-8cm wide, apex acuminate or cuspidate, base attenuate to broadly obtuse, almostÂÂ glaborous when fully developed, when young sparsely puberulent beneath with pale sessile stellate hairs, the lateral nerves 14-21 pairs. |

| Flower | The flower appears at the base of new shoots and is singular, pendant, large and fragrant. The pedicel bears a leaf-like bract and can reach 20 cm in length. The flower’s sepals are red-spotted, crisped and 2.5 cm long. The corolla is formed of six petals of which the three outer reach a length of 10 cm and show curled margins and red, green and yellow spots. The three inner petals are almost triangular and form a white-yellowish cone which on the outside is red-spotted and green on the inside. The flower’s stigmas become receptive before its stamens mature and shed their pollen (protogynous). The flower is pollinated by insects. | Tiny yellow flowers and emits a pungent odor. Staminate inflorescence 2-3 times branched, broadly paniculate, many-flowered, 5-12cm long and almost as broad, on a peduncle 1-3cm long, the branches rusty-puberulent, the flowers in clusters of 5-10, pedicels 1mm long or less; perianth 2mm long, sparsely stellate-puberulent. |

| Fruit and seeds | The fruit is a berry of 20 cm diameter and is smooth, green and spherical and becomes woody. It is attached to a long stalk which is up to 60 cm long. Inside the fruit the numerous oblongoid, pale brown, 1.5 cm long seeds are surrounded by a whitish fragrant pulp. The seeds contain 5-9% of a colorless essential oil. | Fruit on pedicels 5-10mm long, ovoid-ellipsoid, 2.5-3.5cm long, with thick pericarp; seeds 2-2.7cm long, ellipsoid. |

| Origin | Native to the Banda Islands of Indonesia is also grown in Penang Island in Malaysia and the Caribbean, especially in Grenada. It also grows in Kerala, a state in southern India. | Native to the South American rainforest and closely related to other Myristicaceae. Moist or wet forest, ascending from sea level to about 1150 meters; Alta Verapaz; probably Izabal; Sololá, Suchitepéquez; San Marcos; Huehuetenango; Honduras; Costa Rica; Panamá. |

In these photographs you can see the amazing red structure around the seed. This is what is identical in both nutmeg and Virola. I believe this seed is nutmeg (because the leaves are perhaps not as long as expected for Virola). But until we see the flowers we can't be sure either way.

A branch of Virola guatemalensis, nutmeg, with fruits and leaves.

Whole and halved fruits of a plant, whether Virola guatemalensis or Myristica fragrans.

Bibliography of items on-line

- NATIONAL GERMPLASM RESOURCES LABORATORY

GRIN. "Species in GRIN for genus Myristica".Taxonomy for Plants. Beltsville, Maryland: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/splist.pl?7923 Retrieved March 10, 2010.

Has a comprehensive alphabetical list of names of plants of world and has an explication for different genera.

- MISSOURI BOTANICAL GARDEN

2010. "Name -MyristicaGronov. subordinate taxa".Tropicos. Saint Louis, Missouri: http://www.tropicos.org/NameSubordinateTaxa.aspx?nameid=40024462 Accessed March 25, 2013

- ZIPCODEZOO

2012 Virola guatemalensis, present. http://zipcodezoo.com/Plants/V/Virola_guatemalensis/ Accessed March 25, 2013

Nice to have a list but lack of citations is a surprise for a university-related web site. Also, as mentioned in the bibliography elsewhere, his designation of world areas is most politely described as bizarre.

Traditional Bibliography

- Trees and Species of the Flora of Guatemala, p. 649 in Treaties and other international agreements of the United States of America 1776-1949. On-line.

- 2003

- Árboles de Centroamérica: un Manual para Extensionistas (Trees of Central America: a Manual for Extentionists). OFI-CATIE, pages 937-940.

- 1992

- Fruta dorada. Wild nutmeg. Arboles Semillas Neotrop. 1. (1): 45-64 (1992) - illus., col. illus. Icones, Anatomy and morphology.

- 2004

- Manual de Plantas de Costa Rica, Vol. I, Introduction. Missouri Botanical Garden, INBio.

- 1993.

- Propiedades y usos potenciales 100 Maderas Nicaragûenses. Serivicio Forestal Nacional/IRENA, Nicaragua. 178 pages.

- 1987

- p. 1238 mentions Virola guatemalensis

- 2008.

- Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Honduras.

- 2008

- Trees of Guatemala. The Tree Press. 1033 pages.

-

Although the book itself is not on-line, a complete index to this book is available on-line: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2368798#page/1/mode/1up

- 2005

- The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. 3rd Printing edition, Park Street Press, 944 pages.

- 1946

- Flora of Guatemala. Part V. Fieldiana: Botany, Vol. 24, Part V. Chicago Natural History Museum.

- 1963.

- FLORA OF MISSOURI. Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames. 1725 pp

- 1971.

- Maderas Iberoamericanas. VI Bursera simarouba, Poulsenia armata, Pterocarpus oficinales y Virola Koschnyi. 21(:1):69-76

- 2005

- Naked Chocolate: The astonishing truth about the world’s greatest food. North Atlantic Books. 256 pages.

Research by Ilena Garcia, biologist graduated from Universidad del Valle.

Comments. captions, bibliography of books and photographs by Nicholas Hellmuth.

First posted April 2013.