Heliconia Latispatha found at Finca Gangaduwali Livingston, Dec 17, 2020. Photos taken by David Arrivillaga, FLAAR Mesoamerica.

We found over 1 million Heliconia latispatha in one place of Municipio de Livingston

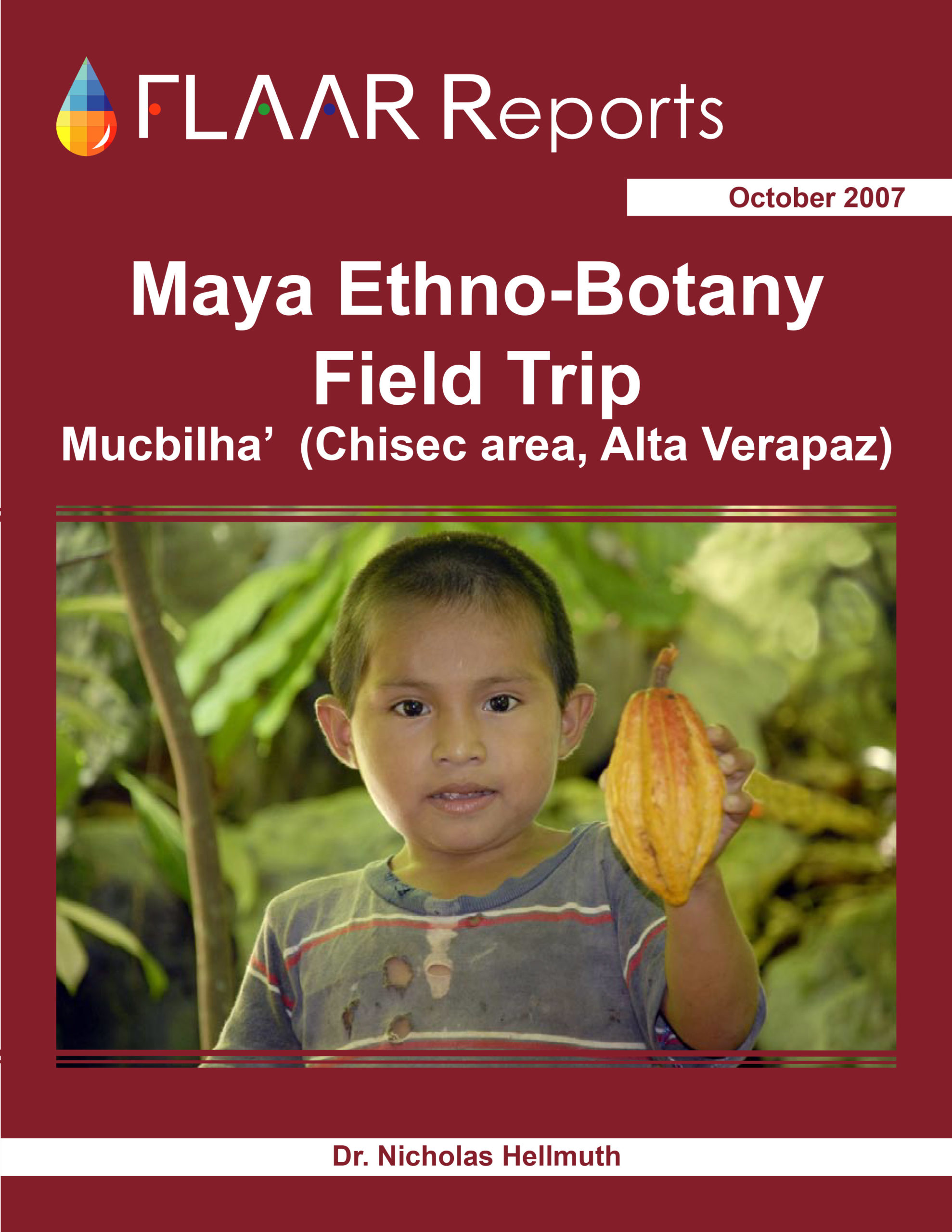

Since most books on Heliconia feature the species from Mexico, Costa Rica, the West Indies (islands) or South America we have dedicated numerous field trips over the recent six years looking for Heliconia native to Guatemala. We are also interested in Heliconia since their large leaves are used by the Q’eqchi’ Mayan people to roof their houses. And many Q’eqchi’ Mayan people use the leaves to wrap tamales (or wrap products to sell in the local Mayan markets).

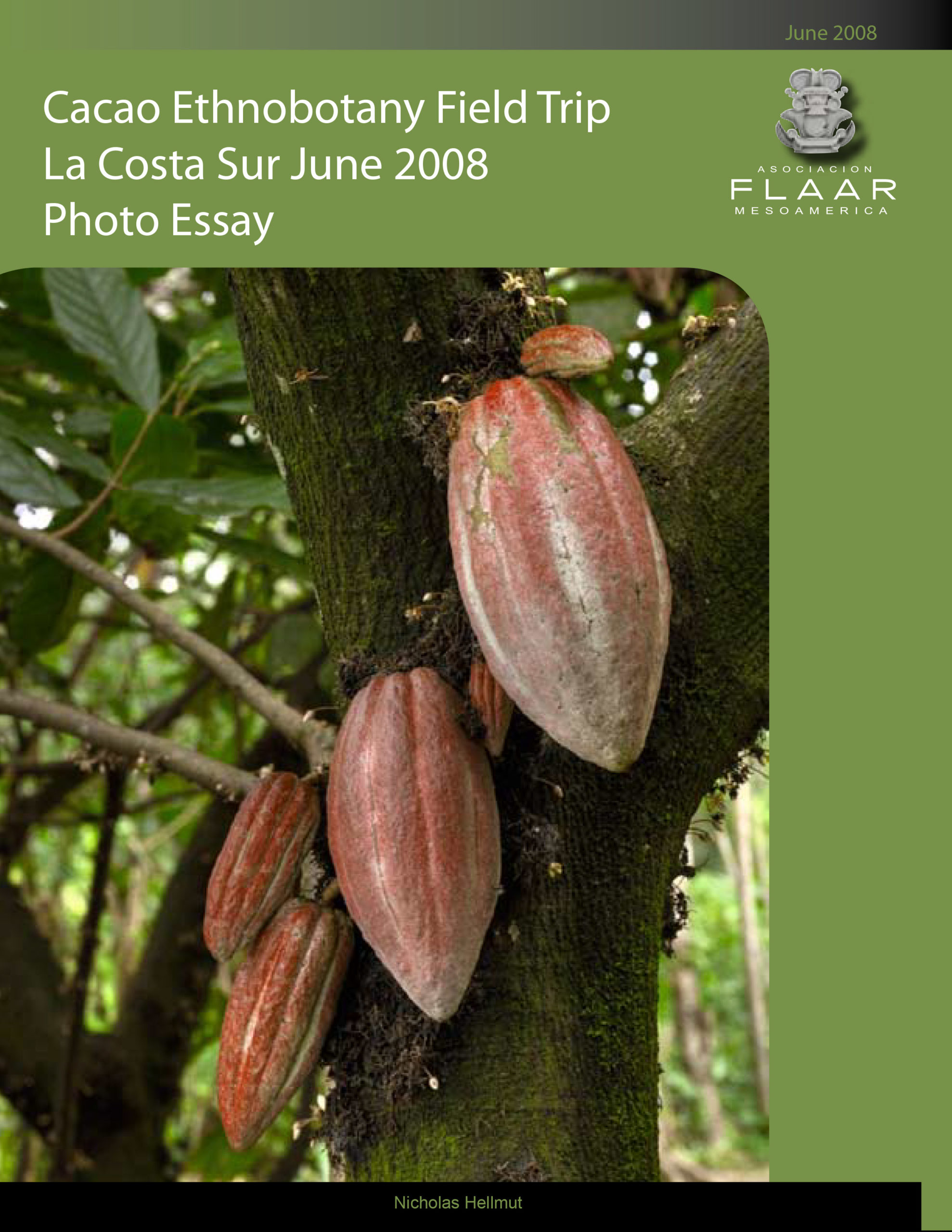

We first saw the literally thousands of heliconia plants while driving from Livingston to Plan Grande Tatin, to visit the Cueva del Jaguar (March 9th, 2020). There was not time to stop the vehicle every time there was a Heliconia flower to photograph. So we returned on March 13th with lots of time available to stop the vehicle, get out, and do close-up photography of the Heliconia (most were starting several kilometers west of Livingston. 95% of the plants were Heliconia latispatha. 5% were Heliconia wagneriana. In other parts of the Municipio of Livingston we found Heliconia aurantiaca. We will have a web page on each of these species; the present page is to introduce Heliconia latispatha.

On March 9th we hiked by foot from Plan Grande Tatin through mud and crossed raging rivers to visit the Cueva del Jaguar. Since we were on foot it was easier to stop and photograph the Heliconia.

We have Heliconia latispatha happily growing for many years in the FLAAR Mayan Ethnobotanical Research Garden, 1500 meters elevation, Guatemala City.

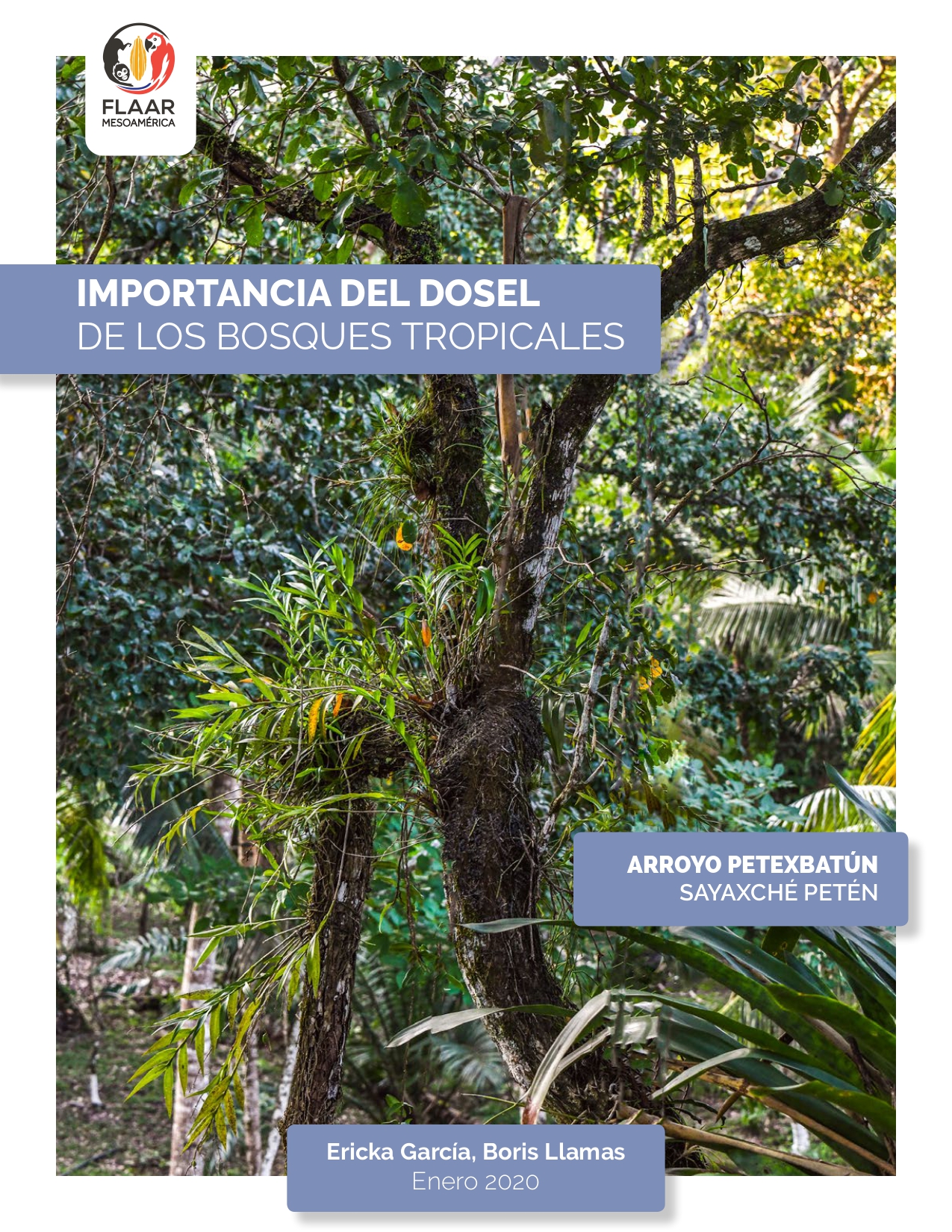

What habitats does Heliconia latispatha thrive in?

Livingston is at sea level (it faces Amatique Bay, an inlet from the Caribbean Sea. Obviously the road from Livingston to Plan Grande Tatin is no longer at sea level; indeed the masses of tens-of-thousands of the Heliconia latispatha grow on the sides of hills. But I doubt elevation goes much beyond 100m.

When driving along the road from Livingston to Plan Grande Tatin, between all the individual maize plants there were lots of 10 cm high young Heliconia latispatha sprouts. So once the maize is harvested the Heliconia grows larger. This results in the literally masses of Heliconia latispatha growing all over hillsides. When the local people get ready to prepare a milpa (slash and burn agriculture) the thousands of Heliconia get chopped down with machetes and burned. But they sprout back up when that next maize crop is harvested. But there are also forest areas or swamp edges where no maize is grown; Heliconia can be found in these areas also (though clearly Heliconia prefers sunlight, it can adapt to some shade from nearby trees).

Cahabon is not as wet as the Municipio of Livingston and is twice the altitude. We have found Heliconia latispatha growing around Cahabon, Alta Verapaz.

What creatures are pollinators of Heliconia latispatha?

I have seen bees buzzing around these flowers in our garden. However keep in mind 1500 meters elevation is not the natural habitat of this heliconia so the pollinators in our garden may not be the same pollinators in Izabal (not much above sea level) and Alta Verapaz (Cahabon is only about 250 meters elevation and is significantly more humid than Guatemala City).

I saw one hummingbird dart onto an inflorescence of Heliconia latispatha, but it flew away so fast I am not sure I got a photograph.

PDF, Articles, Books on Heliconia Latispatha

- 2007

- Trees in the Life of the Maya World. BRIT PRESS, Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 206 pages.

Regina de Riojas has dedicated much of her life to trees of the Maya and trees of Guatemala. Elfriede de Pöll has likewise dedicated her life, to biology of Guatemala, at Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

- 2004

- Plants of the Peten Itza’ Maya. Museum of Anthropology, Memoirs, Number 38, University of Michigan. 248 pages.

Very helpful and nice collaboration with local Itza’ Maya people. But would help in the future to have a single index that has all Latin, Spanish, and English plant names so that you can find plants more easily.

Not available as a download.

- 2000

- Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Belize: With Common Names and Uses. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden Vol. 85. 246 pages.

- 2015

- Messages from the Gods: A Guide to the Useful Plants of Belize. The New York Botanical Garden, Oxford University Press.

- 2005

- Biodiversidad del Estado de Tabasco. CONABIO, UNAM, Mexico. 370 pages.

- 2016

- The forest of the Lacandon Maya: an ethnobotanical guide. Springer. 334 pages.

Sold Online:

www.springer.com/la/book/9781461491101

- 1983

- Flora de Tabasco. Listados Florístico. México 1: 1–123.

- 2010

- Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation.

Figure 21 is a wonderful photograph; first, it is large enough (half page size). Second it is adequately exposed. But most important of all, this helpful photo shows lots of Acoelorrhaphe wrightii around what I estimate is a single Crescentia cujete tree.

- 2010

- Indicadores ecológicos de la zona riparia del río San Pedro, Tabasco, México. MS Thesis, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. 131 pages.

Available Online:

https://ecosur.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1017/1656/1/100000050585_documento.pdf

- 2000

- Etnobotánica Maya: Origen y evolución de los Huertos Familiares de la Península de Yucatán, México.

- 2011

- Árboles de México. Editorial Trillas. 368 pages.

- 1937

- The Vegetation of Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publ. 478. Washington. 244 pages.

- 1938

- Plants Probably Utilized by the Old Empire Maya of Peten and Adjacent Lowlands. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 24, Part I:37-59.

- 2011

- Estado actual y valor de uso etnobotánico de las especies vegetales utilizadas en la industria artesanal alfarera del municipio de Guatajiagua, Morazán El Salvador. Universidad de El Salvador. 54 pages.

Available Online:

http://ri.ues.edu.sv/8952/1/19200931.pdf

- 2003

- Plantas utiles de Peten, Guatemala. Herbario UVAL, Instituto de Investigaciones Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

- 1987

- Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, FL.

- 2018

- Árboles de Calakmul. ECCOSUR, Chiapas. 245 pages.

It is amazing that there is no such book for Parque Nacional Tikal, nor El Mirador. Even though it includes only half the estimated number of “trees,” it has more tree species than Schulze and Whitacre for Tikal (they estimated about 200 but list only about 156 (their lists of species and list by plant family are not identical).

The entire book is a totally free download, however you can’t copy and paste so is difficult to add to your discussion.

Available Online:

http://aleph.ecosur.mx:8991/exlibris/aleph/a22_1/apache_media/74R92GMRSJSEPFDEE5NJY4SJI2I8AK.pdf

- 2008

- Trees of Guatemala. The Tree Press. 1033 pages.

- 2011

- Árboles del mundo maya. Natural History Museum Publications. 263 pages.

Helpful book; contributing authors are experienced botanists. They cover 220 species of trees, more than virtually all other “Books on Trees of the Maya.” Even include tasiste (which is missing from all other books on “Trees of the Maya” except for the recent book on Árboles de Calakmul.

But if all this effort is going into a book, would help if there were more photos, larger photos, and not so much blank space at the bottom of each page. Plus would help if the text could include personal first hand experience with these trees out in the Mundo Maya. But even as is, it is a helpful book.

If you are doing field work you need this, plus Árboles de Calakmul, plus Árboles tropicales de México. Parker’s book you need back in your office, since out in the field it’s not much help due to lack of photographs. Back in your office the books by Regina Aguirre de Riojas are also helpful.

- 2005

- Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principals especies. 3rd edition. UNAM, Fondo de Cultura Economica. 523 pages.

This book is a serious botanical monograph. 1968 was the first edition (I still have this), 1998 was second edition. The 3rd edition is a “must have” book. Each tree has an excellent line drawing of leaves and often flowers and fruits (though to understand flowers you need them in photographs, in full color). Each tree has a map showing where found in Mexico (such maps are lacking in most books on Trees of Guatemala or plants of Belize). But trying to fit a description of a tree on one single page means that a lot of potential information on flowering time is not present. And, this is definitely not a book on ethnobotany: for that you need Suzanne Cook.

- 1919

- Batido and other Guatemalan Beverages prepared from Cacao. American Anthropologist, N.S. 21: 403-409.

- 1968

- Brosimum alicastrum as a Subsistence Al¬ternative for the Classic Maya of the Central Southern Lowlands. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

- 1973

- Ancient Maya Settlement Patterns and Environment at Tikal,

Guatemala. PhD dissertation, Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.

Available Online:

www.puleston.org/writings-dissertation.html

But no pagination, and no copy-and-paste facility.

- 2015

- Settlement and Subsistence in Tikal The assembled work of Dennis E. Puleston (Field research 1961-1972). Paris Monographs in America Archaeology 43, BAR International Series 2757. 187 pages.

This is his wife’s reorganization of his 1973 PhD. No tasiste, no nance could I find. Crescentia cujete is only mentioned as a usable plant, seemingly based on Lundell’s 1938 list rather than Puleston finding it in a savanna. In other words, there is no list in this Puleston opus that suggests he studied or made lists of savanna habitats. And there are no photographs of any savanna. Indeed, the word savanna is not in his index. This is because the focus of all 1960’s-1970’s Maya field work was in traditional archaeology and in hilltop settlement areas. There were no house mounds in savannas so no interest (in those decades) in studying a savanna.

- 1999

- A Classification and Ordination of the Tree Community of Tikal National Park, Peten, Guatemala. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 169-297.

Even though 20 years ago, it’s the best list of trees of Tikal that I have found. There is a web site with plants of Tikal but they are not separated into trees, vines, shrubs, etc., so harder to use. The new monograph on Arboles de Calakmul is better than anything available so far on Tikal (and the nice albeit short book by Felipe Lanza of decades back on trees of Tikal is neither available as a scanned PDF nor as a book on Amazon or ebay).

Free download on the Internet.

- 2000

- A rapid assessment of avifaunal diversity in aquatic habitats of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala. In: Bestelmeyer, B.T. and Alonso, L.E. (eds.). A Biological Assessment of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala, pp. 56-60. Conservation International.

- 1936

- The Forests and Flora of British Honduras. Field Museum of Natural History. Publication 350, Botanical Series Volume XII. 432 pages plus photographs.

- 1931

- Flora of the Lancetilla Valley - Honduras.

- 1952

- Flora of Guatemala, Part II, Fieldiana Bot. Vol. 24, part 3:

Heliconia species are covered on pages 178-191.

- 2013

- Biodiversity in Forests of the Ancient Maya Lowlands and Genetic Variation in a Dominant Tree, Manilkara zapote: Ecological and Anthropogenic Implications.

Free download, but unfortunately you can’t copy-and-paste anything. But the dissertation is helpful as is her subsequent field work and articles.

- 2002

- Homegardens of Maya Migrants in the District of Palenque (Chiapas/Mexico): Implications for Sustainable Rural Development. In: Stepp, J.R., Wyndham, F.S., and R.K. Zarger (eds.). Ethnobiology and Biocultural Diversity. Pp: 631 – 647. University of Georgia Press; Athens, Georgia

- 1972

- A Highland Maya People and their Habitat: The Natural History, Demography and Economy K´ekchi´ PhD dissertation. 475 pages.

His field work was near San Pedro Carcha, which is now a suburb of Coban, Alta Verapaz. The climate is moist due to moist clouds during many times of the year.

Free download on the Internet.

Suggested webpages with photos and information on Licania platypus

www.cicy.mx/sitios/flora%20digital/ficha_virtual.php?especie=324

General information

https://ecosdelbosque.com/plantas/heliconia-latispatha

General information and photos

https://enciclovida.mx/especies/158270-heliconia-latispatha

General information, distribution map and photos

Last update June, 2021

First posted March 16, 2020.

Written by Vivian Hurtado and Dr Nicholas Hellmuth