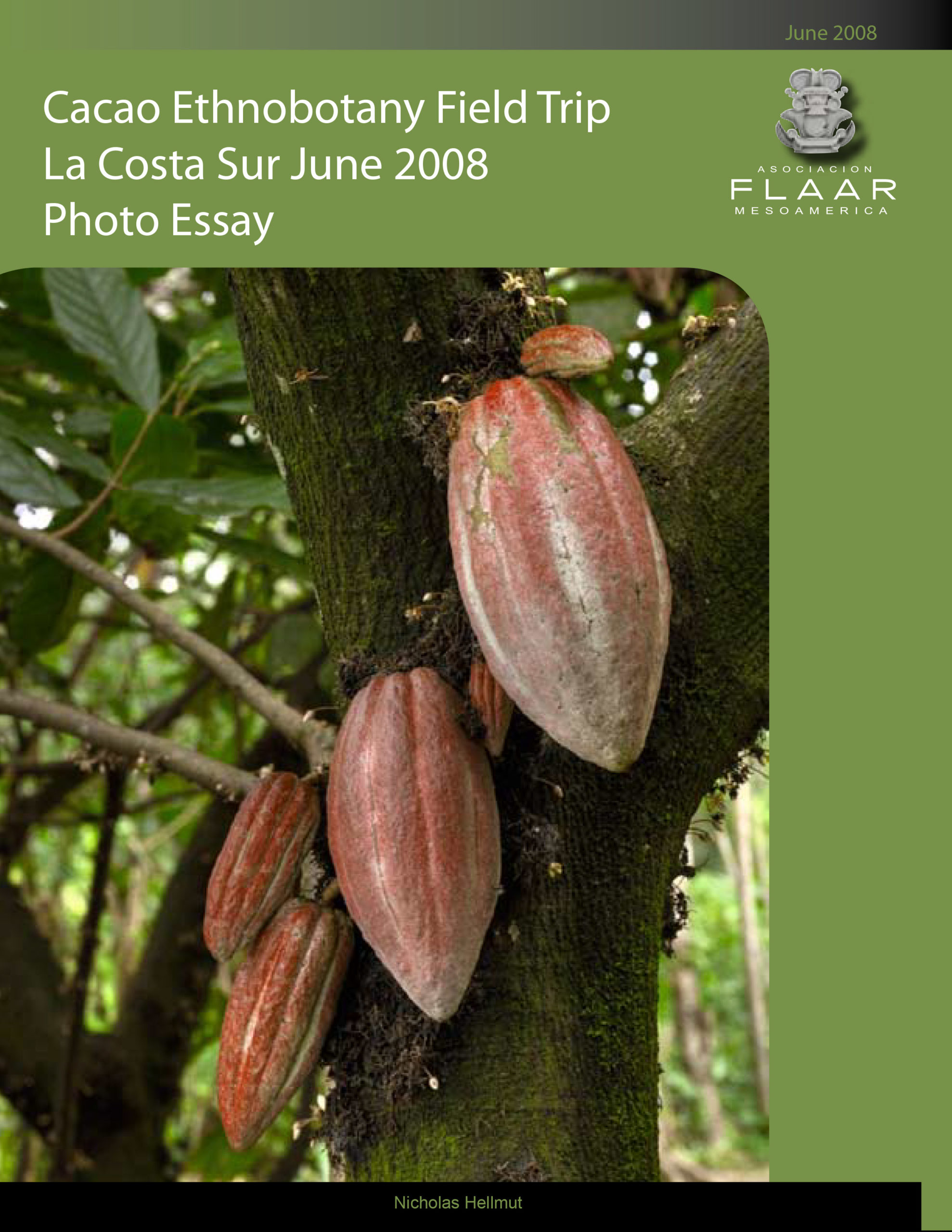

Palo de Brasil is one of the most common trees in parts of the Motagua desert

Much of the Motagua desert is cacti, Optuntia and organ cacti. And many areas have Ceiba aesculifolia (a relative of Ceiba pentandra). The highway from Guatemala City towards Puerto Barrios also goes through groves of literally thousands of Haematoxylum brasiletto trees, from km 70-ish through km 104, and even some Palo de Brazil up to the Manzanal area. But anywhere near the Quirigua area of the Rio Motagua there is no Palo de Brazil whatsoever: too moist (would be worth checking to see where Palo de Campeche is able to start, probably on the north, around Amatique Bay and Rio Dulce, which is not in the same zone as the Rip Motagua).

My interest in this tree is:

- This is a source of colorants (as would be expected from the closest relative of Haematoxylum campechianum).

- Palo de Brasil is in the serpentine geology area where in some places you can find jadeite. Although FLAAR is not actively working with geology of the Maya area we are keenly interested since as a student at Harvard I discovered and excavated considerable quanity of jade jewelry in the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar under a pyramid in Tikal (three volume report is available as a download, at no cost). There was also iron pyrite in this tomb: indeed three entire pyrite mosaic mirrors.

- Palo de Brasil has medicinal use (not listed by Parker 2008:404 but available in technical articles, plus expected because Palo de Campeche has multiple uses, potentially even as a flavoring).

- But most of all, my interest in Haematoxylum brasiletto is because probably 95% of the books on the Maya which list utilitarian trees do not list this species (clearly because they don’t know of it, not surprising since it is (technically) not (yet) known to grow in the Maya Lowlands nor Highlands). The Motagua deserts is somewhat outside the core Maya areas (though Quirigua and Copan are less than 70 miles away).

Is Palo de Brasil also a flavoring?

Much to my surprise, Palo de Campeche, tinto, is a flavoring (edible). This raises the question of to what degree is Palo de Brasil also a potential source of a flavoring.

And is the colorant edible, or not? Lots of research potential here for a thesis or PhD dissertation.

Should you spell the genusHaematoxylum or Haematoxylon?

Haematoxylon Brasiletto Karst. (Standley and Steyermark 1946:138).

Haematoxylum(Standley and Steyermark 1946:204). So in the same botany monograph he spells the species name in two different ways.

Haematoxylum brasiletto H. Karst. (Parker 2008:404). Haematoxylum brasiletto H. Karst. is in the family Leguminosae.

Should you spell it BraZil or BraSil?

It is always spelled (by botanists) as Palo de Brasil, because this is how to spell that country in Spanish. In English it would be with a z, Brazil.

There is another tree, Caesalpinia echinata of thepea family, Fabaceae, which produces dye and is called Palo de Brazil. This is the national tree of Brazil.

A totally unrelated tree, Dracaena fragans, is also called Palo de Brazil. Dracaena fragans is a common house plant and sold in many nurseries. Dracaena fragans is not a dye plant whatsoever and iconically is native to Africa.

My personal experience with dyewood trees in Guatemala

I learned about Palo de Tinto already ate age 19, when I noticed remains of Haematoxylumcampechianumin the royal tomb that I discovered and excavated at Tikal.

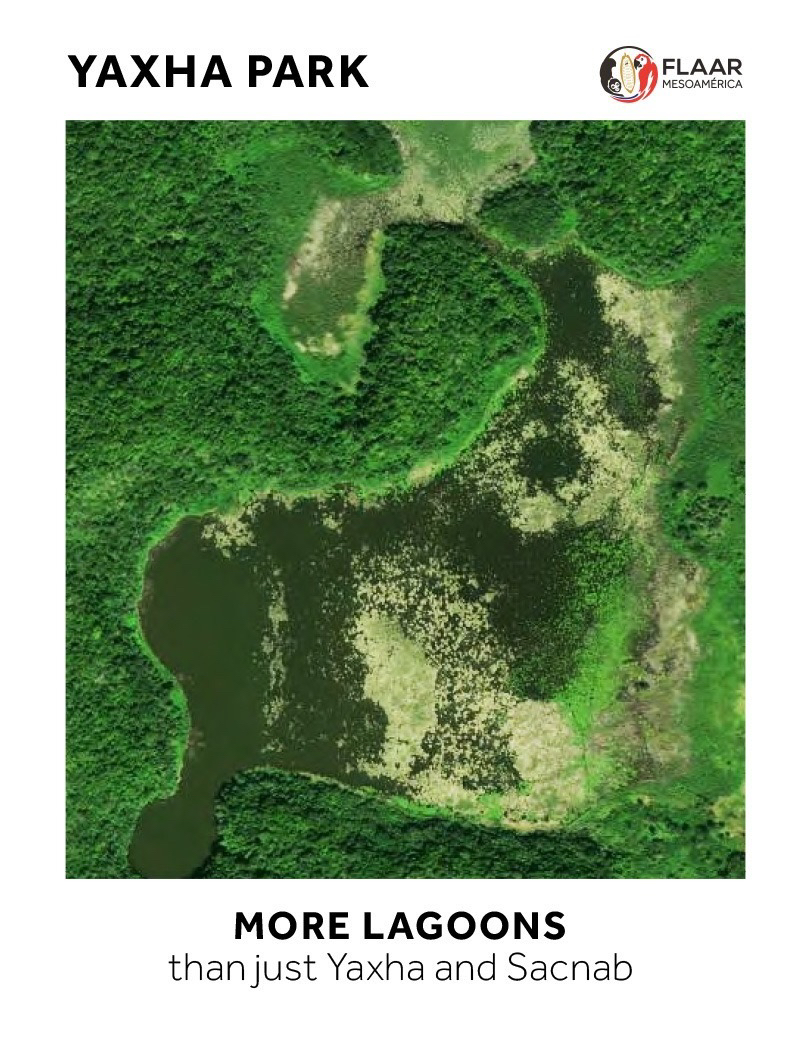

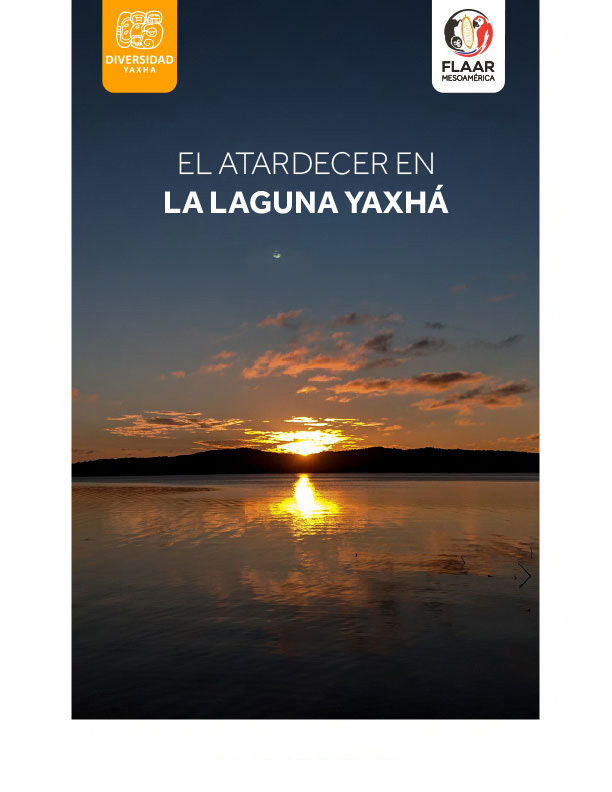

I then had five years familiarity with Palo de Tinto while living along the shore of Lake Yaxha, El Peten, while mapping the Maya ruins of Yaxha. There are substantial stands of tinto between Lake Yaxha and Lake Sacnab. FLAAR worked here five seasons and was able to save this remarkable eco-system by having a national park declared based on our lobbying on behalf of this area with FYDEP and various park services.

I then experienced palo de tinto every year that I led tour groups to the Lake Petex Batun area near Sayaxche. The Arroyo Petex Batun used to be lined with Palo de Tinto (now most is illegally cut by local people). Obviously I also saw Palo de Tinto while leading tour groups to Belize. And anyone who travels in Belize knows that logwood is the reason the British settled here (logwood was the main source of dye for the British wool industry until cheap chemical dyes became available).

It is ironic that I never saw Palo de Campeche in Campeche!

Yet in these several decades of experience with Palo de Tinto in swamps and along river shores, I had no idea about the almost identical Haematoxylum species that grows also in Guatemala, but in theory only in the dry deserts, Haematoxylum brasiletto. Earlier I had noticed that Haematoxylum brasiletto was common in deserts of Mexico, such as in Sonora and Oaxaca.

Then in 2012 (almost half a century after learning about Haematoxylum campechianum, I noticed that I had been driving by thousands of Haematoxylum brasiletto trees for decades: Palo de Brazil is the most common tree alongside the main highway in Guatemala (CA9, from the capital towards Puerto Barrios), even before the turnoff at El Rancho (north to Coban, Alta Verapaz). Thomas Schrei, a biology student from Universidad del Valle, was on this field trip and he was the one who pointed out the Palo de Brazil.

Location of Haematoxylum brasiletto

Haematoxylum brasiletto probably grows in several areas of Guatemala but where I see it the most often is alongside the highway from Guatemala City towards Puerto Barrios. The trees begin perhaps km. 60 and at least by km. 70 and continue through at least km. 90. If you had time and budget to study this plant you could make a more accurate list of its range.

What I notice the most is that for part of this stretch, especially before the areas where Ceiba aesculifolia and cacti are really abundant (km 80-100), the Palo de Brazil is the most common tree along the roadside (and it is not planted).

Palo de Brasil also continues up in the high hills from El Rancho up towards the start of the pine and oak forests. Obviously the Palo de Brasil is not present any more once the pine and oak forests begin.

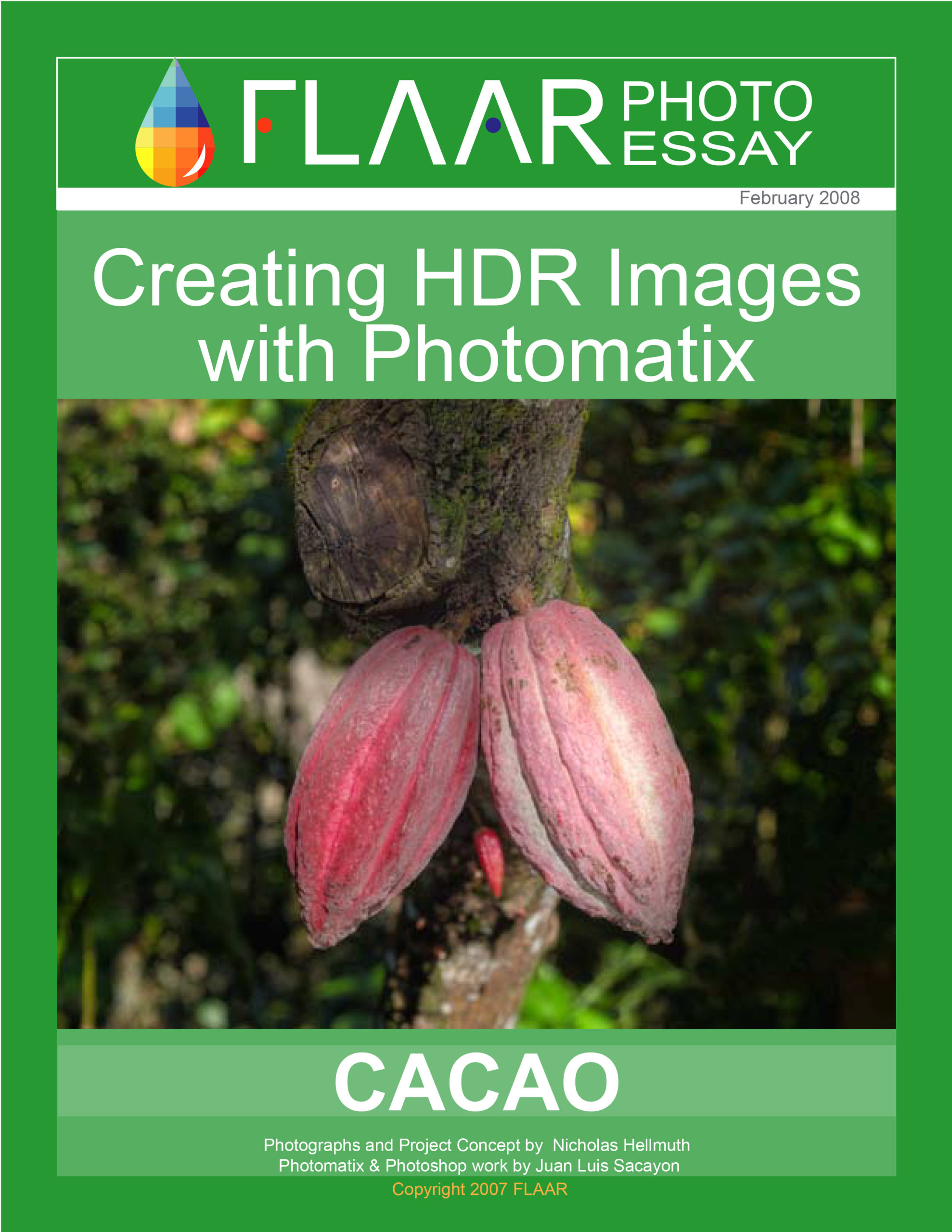

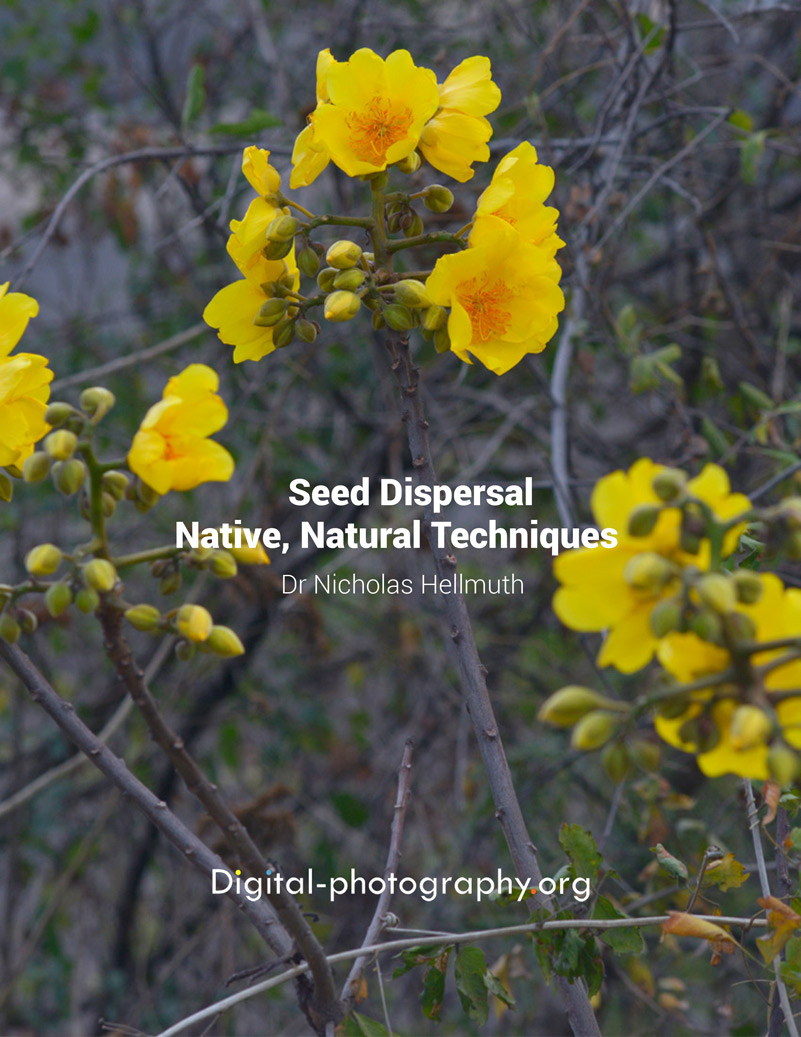

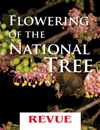

Haematoxylum brasiletto flowers for several months

During several months the Palo de Brasil trees along the Carretera al Atlantico were in full flower. What surprised me was that the flowering lasted several months: December, January, February. Since there were thousands of trees I have no realistic way to determine if an individual tree remained in flower the entire time.

Then in late March I noticed still more flowers. Now only perhaps 1% of the trees were flowering. When driving down a highway it is not easy to tell the difference between fresh leaves and flowers (or dying yellow leaves and flowers). For example, if you had never been to Guatemala before, and you saw the fresh leaf buds of a Ceiba pentandra tree, you would think the trees were flowering! The fresh leaves are a totally different color than the mature green leaves.

But when we stopped to photograph Ceiba aesculifolia we found a Palo de Brazil still with fresh flowers on it, albeit not totally covered.

In many areas the Palo de Brasil trees were in areas so dry that the main plants in the same area were cacti. As mentioned above, this is also a habitat favored by Ceiba aesculifolia. This ceiba species seems to prefer dry areas, especially dry slopes. Although Ceiba pentandra also grows along the highway through the same Rio Motagua desert area, Ceiba pentandra is more common in the significantly more moist Costa Sur, Alta Verapaz, Izabal, and El Peten.

I do not spend enough time in the Huehuetenango around Santa Ana Huista to notice whether Palo de Brasil grows there also. Standley and Steyermark list it for there (1946:138; copied by Parker 2008).

Be careful about web sites which confuse Palo de Brazil with Palo de Campeche

Even articles by botanists sometimes confuse these two close relatives. I presently prefer to keep the two species totally separate:

- Palo de Brasil: dry areas, including dry deserts; often on hillsides.

- Palo de Campeche: wet areas (seasonal swamps, or along rivers or lakes). Not expected on a hillshide (I find them mostly on flat areas).

- Palo de Brasil: totally filled with thousands of yellow flowers when it blooms.

- Palo de Brasil: flowers last for months

- Palo de Campeche: tough to notice the flowers

- Palo de Campeche: not yet convinced that the flowers last very long.

Above is the nice and simple way to view the situation. However the reality gets more complicated if Palo de Brazil co-inhabits in the Peten.

Is Palo de Brasil, Haematoxylum brasiletto, also native to Peten?

Lanza mentions only Palo de Campeche for Tikal (107ff:1996).

The Chicago Natural History Museum botanists do not list Palo de Brazil for Peten (but one would question whether they spent much time there, since Lundell’s information was already available).

Most botanists cite the standard statement:

Dry rocky brushy hillsides, 200-1,200 meters; Zacapa; Chiquimula; El Progreso; Baja Verapaz; Guatemala (Fiscal); Huehuetenango (region of Santa Ana Huista). Western Mexico; Salvador to Costa Rica; Colombia and Venezuela (Standley and Steyermark 1946:138; identical in Parker 2008:404). Neither lists Palo de Brasil for Peten.

But Lundell does list Palo de Brasil specifically for El Peten (1937:pages 28, 30, 63). He writes about the two in the same tone. Lundell makes no mention whatsoever of the unexpected fact that Palo de Brasil is a desert plant. So why is a desert tree in seasonal swamps adjacent to Palo de Campeche?

When I was asking to be shown flowers of “palo de tinto” a few kilometers from Flores, El Peten, the local gardener told me there were two kinds of palo de tinto. “white” and another color (not meaning the flower; probably the bark). There is zero mention of this in Standley and Steyermark or any other botanical monograph that I can yet find. And it’s impossible to find anything by Google since the color names are too common with other topics.

Now that I understand that possibly Palo de Brazil may be in Peten, I will return when the palo de tinto trees are flowering to see which species is blooming.

Either there are two species, or two varieties of one species. This will be an interesting contribution to the botany of El Peten, Guatemala.

Palo de Brasil is also a medicinal plant

The medicinal use of both Palo de Brasil and Palo de Campeche is a whole other study (www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/monografia.php?l=3&t=&id=7910)

Concluding remarks on Haematoxylum brasiletto

Most books on trees of the Maya area do not include or mention Palo de Brasil; most books focus exclusively on Palo de Campeche (Trees in the Life of the Maya World is a good example). But the Haematoxylum brasiletto grows precisely in the jade area of the Rio Motagua. There were surely plenty of jadeite miners there two thousand years ago and surely they made use of Haematoxylum brasiletto. The tree makes good charcoal, for example. There is plenty of stone on the surface and road cuts which looks like serpentine in much of the area where you can see Ceiba aesculifolia.

Although the easiest area to see Palo de Brasil in Guatemala are the literally thousands of trees lining the Carretera al Atlantico (especially km 70 through 90) you can also experiment driving up to Salama (Baja Verapaz). That road takes you through more dry areas where you would expect Palo de Brasil. Plus there is less traffic so easier to park along the highway to do your research.

Parker covers Haematoxylum brasiletto on her pages 404-405. Her helpful work is a compilation of what is in the multiple volumes of Standley, Steyermark and other botanists. You can find all the original info for Palo de Brasil in Standley and Steyermark 1946.

When possible I prefer to work out in the fields, forests, deserts and mountains. I do not work in herberariums. I love botanical gardens but I prefer to be out in the real actual eco-systems. Thus I spend a lot of time enjoying experiencing the gorgeous display of yellow flowers of Palo de Brasil along two highways: CA9 and the turn-off from El Rancho towards Alta Verapaz.

Introductory bibliography onHaematoxylum brasiletto

- 2007

- Trees in the life of the Maya World. Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 206 pages.

- 1966

- Manual de los Árboles de Tikal. Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional. 124 pages.

- 1937

- The Vegetation of Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Pub. No. 478.

- 2008

- Trees of Guatemala. The Tree Press. 1033 pages.

- 1946

- Flora of Guatemala. Part V. Fieldiana: Botany, Vol. 24, Part V. Chicago Natural History Museum.