Molinillo, Rosita de Cacao, Quararibea funebris, Tikal, Guatemala.

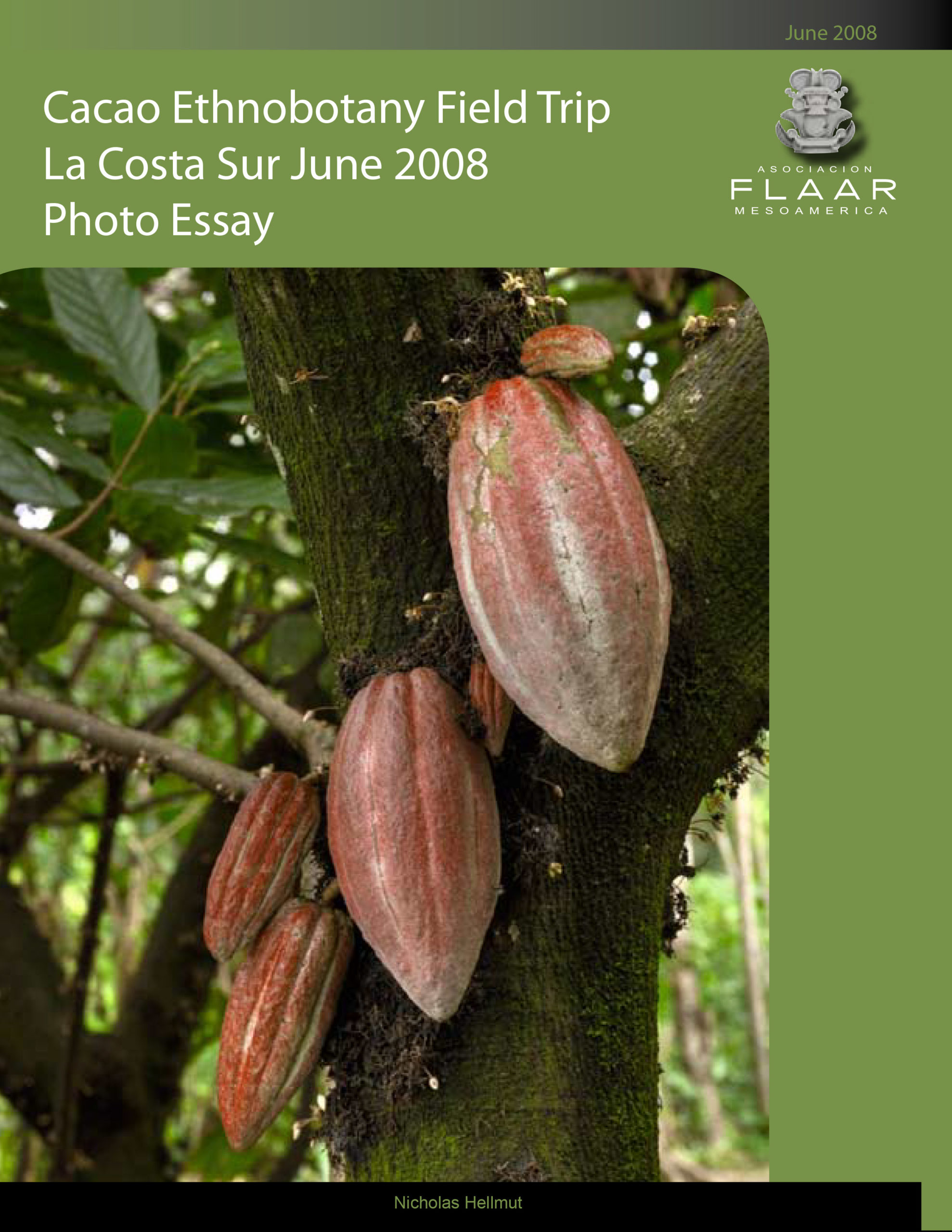

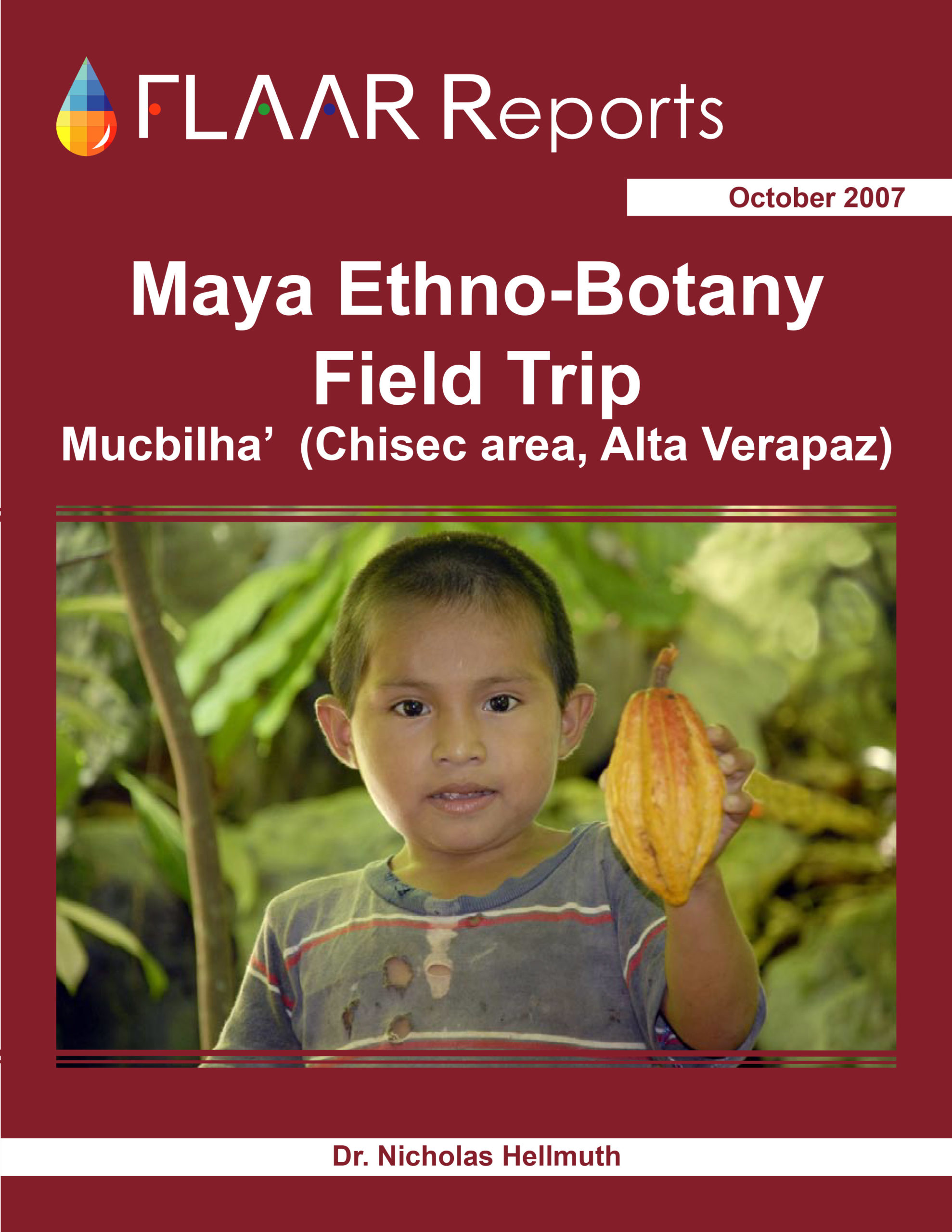

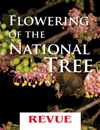

This FLAAR Report introduces the multifaceted Quararibea funebris, found in many areas of Guatemala but so far we have found only one single tree, in the Parque Nacional Tikal.

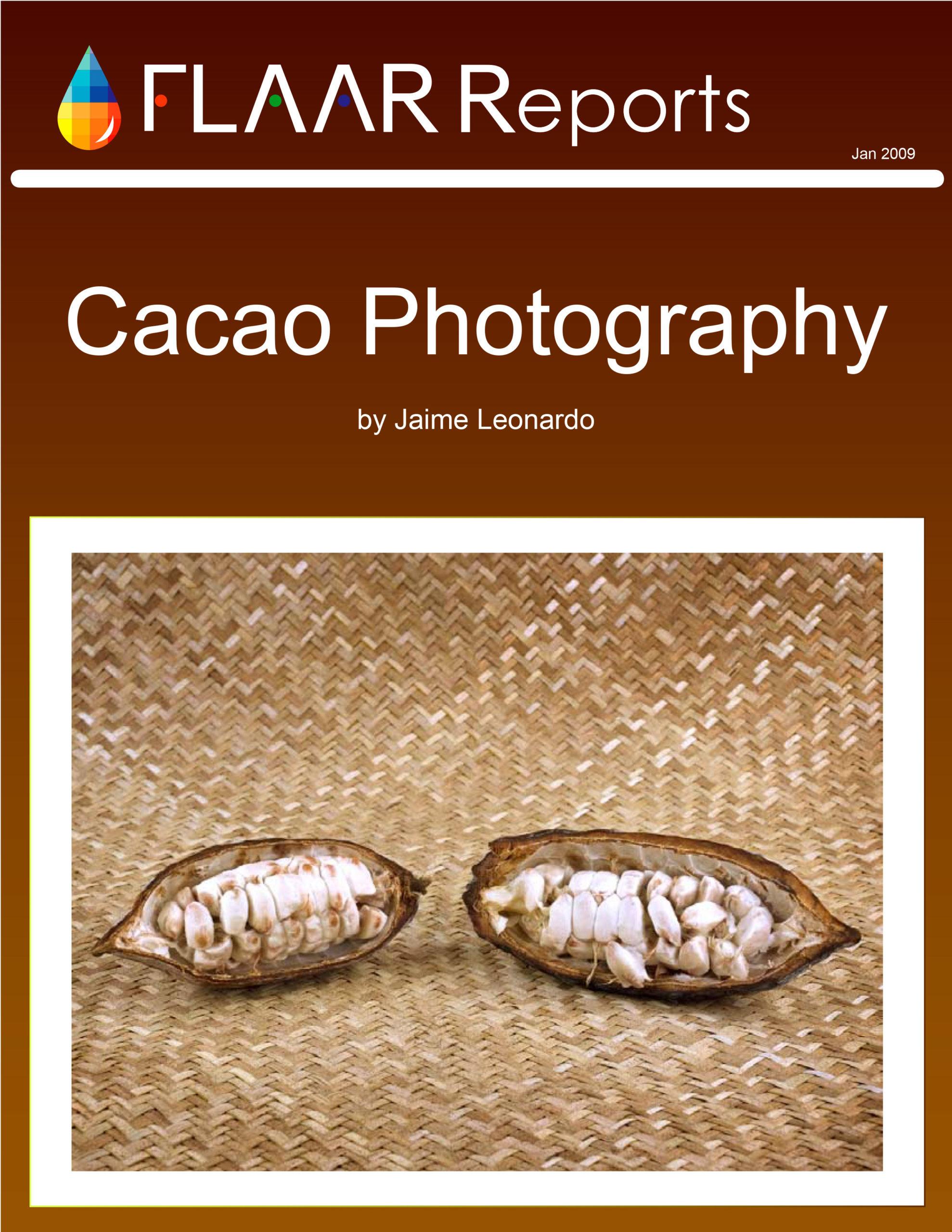

The best known local name is molinillo. Molinillo means it is the spoon which stirs something (in this case the cacao). Also called batidor and Sapotillo.

Another nickname, madre de cacao, really means any tree that is commonly used as shade for cacao orchids or plantations. It is typical in Spanish that several totally different trees end up with the same name. So Gliricidia sepium is also named madre de cacao (and Gliricidia sepium is also a flavoring for chocolate). But Gliricidia sepium is not named rosita de cacao. So I will tend to use the word madre de cacao for Gliricidia sepium and will call Quararibea funebris rosita de cacao or molinillo.

Quararibea funebris, Molinillo Rosita de cacao, cacao chocolate flavoring. Parque Nacional Tikal, El Peten, Guatemala.

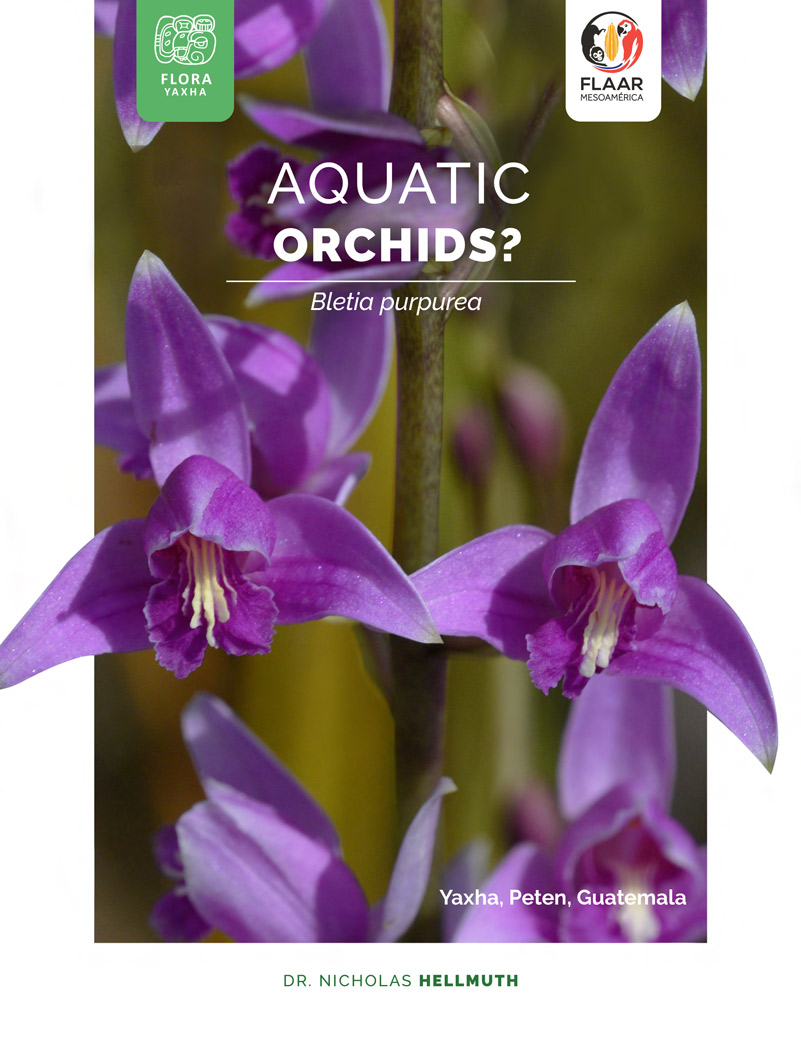

Quararibea funebris, fragrance and taste

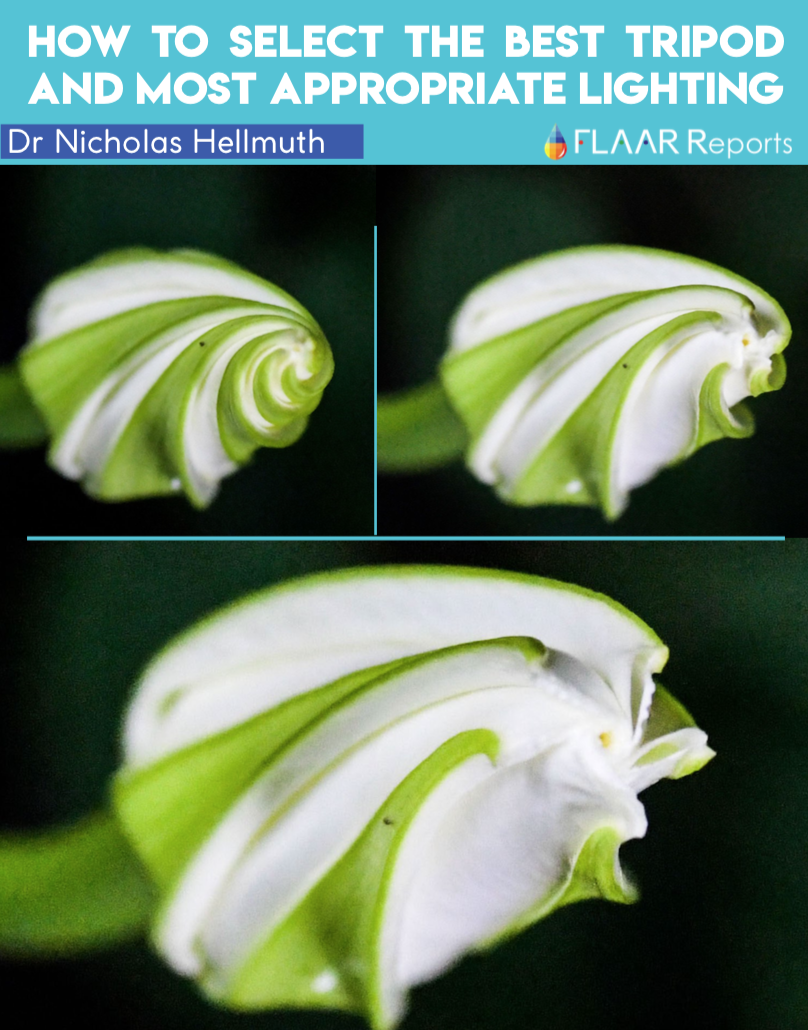

In three years search we have found only one single tree, at the Parque Nacional Tikal. And this one tree, which we have visited on several occasions throughout the year, was blooming only one time (March 22, 2013). It had only one single solitary flower on the entire mature tree that day!

But one is better than none, and we show the flower here. Molinillo trees are reportedly common in the Oaxaca area (http://toptropicals.com/html/toptropicals/plant_wk/quararibea.html)

The smell was impactful. I would rate it as the most tasty fragrance of anything that I have experienced other than nutmeg (or Virola), other than Brugmansia, and other than night blooming jasmine (a common garden plant throughout Guatemala).

We do not tend to taste-test the plants or flowers that we study (especially not Brugmansia). But we definitely do enjoy having a smell-test.

Although there are many spices for Maya foods, we focus on finding more Quararibea funebris. One of our staff felt there were several Quararibea funebris trees at Candelaria Campo Santo. But the people we asked did not recognize the names Rosita de cacao or molinillo. Perhaps we need to find the Q’ekchi or at least the Itza Maya name for this tree.

Funeral tree: molinillo flowers are used in burials

Besides flavoring chocolate and making desserts, the native peoples used the plant for preserving food and bodies. The fragrance stays in dry flowers for decades, thus they were used for funeral ceremonies and were found in crypts still fragrant after many years. This feature of the flower gave another common name to the plant - Funeral Tree (http://toptropicals.com/html/toptropicals/plant_wk/quararibea.html).

As typical on the Internet, this web site blissfully neglects to cite the source of the above information.

Species names; family names; sub-family designation: constant changes

Botanists write articles every decade or so changing the family names and species names. We are so busy looking for the trees out in the tropical forests and swamps that we have little time to keep up with what occupies all the capable scholars back in their universities. So we stick to the basic names. Future scholars will rewrite everything anyway, now that you can do DNA analysis of plants.

Quararibea funebris, Molinillo Rosita de cacao, cacao chocolate flavoring. Parque Nacional Tikal, El Peten, Guatemala.

But we are aware that many botanists no longer consider Bombacaceae as a legitimate separate family. These botanists prefer to create a subfamily Bombacoideae within the family Malvaceae.

Various species exist but the most common one is Quararibea funebris

Veliz (2000) found a new subspecies of Quararibea yunckeri subsp. izabalensis on the Sierra Santa Cruz and reports it to be simpatric with Q. funebris. His article is especially useful as he carefully and clearly shows on a map precisely where he found each group of trees. But the primary tree that is available to study throughout the Maya area is Quararibea funebris.

- Quararibea funebris (Parker 2008:104-105).

- Quararibea fieldii (mostly but not exclusively in Yucatan)

- Quararibea yunckeri (Parker 2008:105).

Keep in mind that Parker’s monograph is almost totally a compilation of copy-and-paste from all the Standley and Steyermark and other botanical field work monographs. Although she was indeed in Guatemala and hence had local knowledge potentially available, her work appears still to be a compliation and not additional new field work.

Arboles del Mundo Maya lists

- Quararibea fieldii

- Quararibea funebris

- Quararibea gentlei

- Quararibea guatemalteca

But says nothing about any species other than Quararibea funebris. The text has an unexpected note that “similar species” are Virola and Compsoneura. Virola is a remarkable fruit, identical in size, shape, and color to a close relative from Asia, nutmeg. Could be Compsoneura sprucei (A.DC.) Warb. or Compsoneura mexicana (Hemsl.) Janovec. Both Virola and Compsoneura have blood-red sap, but I am not yet familiar with the sap of Quararibea funebris. I do not associate blood red sap with any Bombacoideae.

Pennington and Sarukhan list only Quararibea funebris and do not give any uses other than as flavoring for cacao and posol (1968:298).

Parker’s complilation indicates that Quararibea gentlei and Quararibea guatemalteca are synonyms of Quararibea funebris (2008:104-105).

General situation of rosita de cacao in Mesoamerica

Quararibea is a genus (originally) listed as a genus within the Bombacaceae family, the same as the Ceiba tree, the are two main groups branching in this family one is composed of species with compound leaves and the other with simple leaves. Quararibea belongs to the simple leaves group. (Gentry 1996).

Standley and Steyermarki ( 1949) describe the species in The Flora of Guatemala:

“Quararibea funebris (Llave) Vischer, Bull. Soc. Bot. Geneve II. 11: 205. 1919. Lexarza funebris Llave in Llave & Lex. Nov. Veg. Descr. 2: 12. 1825. Myrodia funebris Benth. Journ. Linn. Soc. Bot. 6: 115. 1862. Molenillo.”

Quararibea funebris, Molinillo Rosita de cacao, cacao chocolate flavoring.

Moist or wet forest, 2,100 meters or lower, often in thickets or forest along stream banks; Santa Rosa; Escuintla; Suchitepequez; Retalhuleu; Quiche"; Huehuetenango. Southern Mexico; Salvador; Nicaragua.

A shrub or small tree, in Guatemala seldom more than 10 meters tall, sometimes attaining a height of 20 meters, the trunk sometimes 30 cm. in diameter, the branches often somewhat pendent, the crown broad and depressed, the branchlets minutely stellate-lepidote; leaves short-petiolate, oblong to oval or elliptic, sometimes oblong-obovate, mostly 15-25 cm. long and 6-10 cm. wide, often larger, obtuse to short-acuminate, rounded or obtuse at the base, glabrous except for the small dense tufts of hairs beneath in the nerve axils; flowers mostly solitary, the pedicels 2 cm. long or less; calyx about 2 cm. long, turbinate, greenish, minutely tomentulose, the lobes very short; petals white, thinly tomentulose, recurved and about equaling the calyx, narrowly lance-oblong; stamen tube twice as long as the calyx, stellate-puberulent; ovary 4-celled; fruit globose, mostly enclosed in the persistent calyx.

Called "canela" in Veracruz, and known in other parts of Mexico as "flor de cacao," "madre de cacao," and "rosa de cacao"; the Nahuatl name was "cacahuaxochitl" ("cacao flower"). The species was described from a tree growing at Izucar, Puebla, Mexico, to which it is said that the Indians formerly resorted "to mourn their dead." Just what this may mean is uncertain, but the tree evidently had some religious significance. The fragrant flowers are added to "pozonque," a cold beverage made from cacao, to flavor it. In Costa Rica the young shoots of some species of Quararibea, with their whorls of side branches, are used to make molenillos, utensils with which chocolate and other beverages are beaten to a froth. The wood in this genus is chalky white or slightly yellowish, not highly lustrous, subject to blue-stain; sapwood not clearly defined; rather hard and heavy, straight-grained, medium-textured; tough and strong, easy to work, takes a smooth finish, is not durable when exposed.”

So far I have not found Quararibea in 90% of the reports on Q’eqchi language and culture and even in PhD dissertations on ethnobotany of the Q’eqchi. Yet surely this tree grows throughout Belize and must be somewhere in Alta Verapaz as well.

The tree is actually relatively common throughout Peten: not in terms of thousands of trees in any one location, but being listed in many eco-systems.

Names for Quararibea funebris in English:

Funeral tree, bass, swivel stick tree, swizzle stick tree (Belize). Elsewhere I found funeral tree by itself (so not “funeral swizzle stick tree”).

Names for Quararibea funebris in Spanish:

bastidos, batidos (Belize); canela (Mexico); cincho, coco mama (Belize); cocomama, cocomana (Honduras); flor de cacao (Mexico); garroche (Costa Rica); madre de cacao, maricacao, molinillo (Mexico); moro (Guatemala); palanco (Costa Rica); palo capado, palo de molinillo (Mexico); pataste (Nicaragua).

Remember that in Guatemala Pataxte means Theobroma bicolor, a close relative of cacao (Theobroma cacao).

Name for Quararibea funebris in Mayan

To make more complete lists in the languages of Mesoamerica we need a grant or funding for a linguist, but in the meantime, we have the name in two languages. Surprisingly the name is very similar both in the Highlands of Chiapas and Lowlands of central Peten.

- majáz (Tzeltal. Pennington and Sarukhan 1968:298).

- Aj maja’as (Itza Maya, Atran et al 2004:210

Name for Quararibea funebris in Nahuatl

cacahoa-xochitl

(www.wdt.qc.ca/treesna2list.asp?start=6501)

Cacahuaxochitl = flower of cacao

Xochicacahuatl = precious flower

For Poyomatli or poyomaxochitl there is no common agreement as to which flower is the correct translation. But whatever flower it was must have had impactful effects.

Practical uses, other than symbolic

Called funeral tree because the flower is used as a fragrance for burials. Since a human body might tend to smell rather rancid in the tropics (even with all the local substances to preserve it at least a day or so), you can calculate that a really sweet smelling flower would help during burial.

Would be fascinating to see if any traces of Quararibea funebris can be found inside a Maya (or Mixtec or Aztec) burial. Remains of at least some plants were found in burials at Copan, Honduras.

Rosita de cacao may also be smoked

The current ethnobotanical research projects we have are:

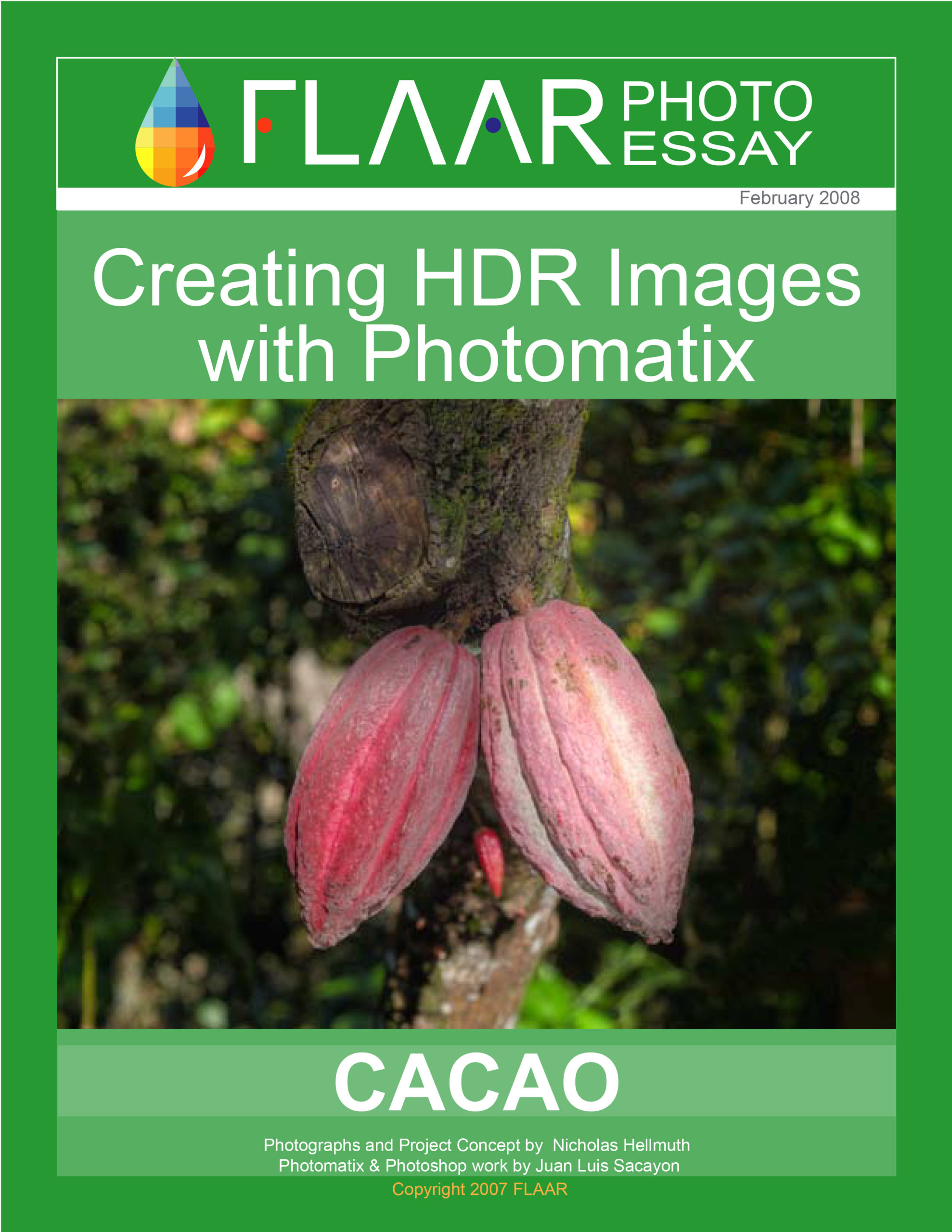

- Flavoring for cacao

- Flavoring for tobacco and other plants which are smoked besides tobacco

- Flavoring for incense; which plants are used both for tobacco and/or cacao and/or for incense

There are thus three series of web pages: on flavoring for cacao are most advanced; next are the flavorings for tobacco. For flavoring for incense we have begun but still need several years field work (and studying what is in the local Maya markets). So we do not yet have many web pages and only a few PDFs on the topic of ingredients for incense.

Although we still are doing research on flavoring for tobacco, we already have located at least one web site on tropical plants which suggests that molinilla, Quararibea funebris, Rosita de cacao, can flavor tobacco. http://toptropicals.com/html/toptropicals/plant_wk/quararibea.html

It is worth noting how many of the flavorings for Aztec and Maya cacao were drugs of one form or another. I would need to check on all recent monographs on cacao to see to what degree this has been noticed, and if noticed at all, whether a clear conclusion was made.

Other interesting plants in the same or related family

Related species (within the Maya area) include Pachira aquatica (common in Guatemala) and Bernoullia flammea, which is a flavoring for tobacco. Parts of Pachira aquatica are edible.

Parts of the Ceiba aesculifolia (Pochote) are also used as a spice for cacao.

Note that these three species are all trees of the (former) Bombacaceae family.

Habitat of rosita de cacao in the Mesoamerican area

Quararibea funebris is present in the Selva Lacandona, noted at Yaxchilan, including amidst the Maya ruins (Meave et al. 2008:58, 60).

Velez shows many stands of Quararibea species in the area where Izabal and Alta Verapaz border each other. However this area is either destroyed by the Exmibal mining operations, or bulldozed for sugar cane plantations, or bulldozed and burned to the ground to plant African oil palm, or chopped down to create cattle pastures.

When does Quararibea funebris flower? When is fruit ripe?

We are still unable to find adequate information on phenology of most of the plants of Guatemala. There is much more information on the plants of Costa Rica but since the soil and climate of Guatemala may be different than that of Costa Rica, the phenology in lower Central America is better than nothing but is not a realistic guide for Guatemala.

In 2013, the tree at Tikal had its single flower in late March. But the eco-system of Tikal, El Peten is different than that of the Costa Sur or Izabal.

In 2015 the Quararibea funebris trees on the Costa Sur bloomed in early June. By the last week of June the flowers were either fallen off or too dry; the plant scout said it was not worth driving down by that date.

So the flowers bloom only perhaps over a period of two weeks (if on a mature tree with hundreds of buds). If a young tree with only a few buds, they seemingly really do only look photogenic for one or two weeks at most.

Rosita de cacao in Mayan art & Archaeology (artifacts)

Charles Zidar interprets that some flowers pictured on Classic Maya vases are the Quararibea fieldii.

Rosita de cacao in Oaxaca

Tejate, a beverage that includes Rosita de cacao, is made and consumed in Oaxaca including the town of San Andrés Huayápam.

Best books, articles and websites on Quararibea funebris

To assist students, scholars, and the general public who have an interest in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica we provide the bibliography below. Our focus is primarily the Maya, though we do keep track of foods of the Aztec. We try to note the foods of the Mixtec of Oaxaca, Mexico as well, but our focus is rather clearly on Guatemala since the trees here are easier to find in the forests, reserves and national parks.

Molinillo is missing totally from Plantas utiles de Peten Guatemala (MacVean 2003). And as mentioned in the discussions, Quararibea funebris is conspicuously missing from most discussions of the plants of Alta Verapaz in general and Q’eqchi plants in particular.

- 2007

- Trees in the Life of the Maya World. BRIT PRESS, Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 206 pages.

Regina de Riojas has dedicated much of her life to trees of the Maya and trees of Guatemala. Elfriede de Pöll has likewise dedicated her life, to biology of Guatemala, at Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

- 1986

- Quararibea Aubl. s.l. (Bombacaceae) in Mexico, Central America and the Antilles: a taxonomic study. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison. 464 pages.

- 1987

- A new Subspecies of Quararibea Funebris (Bombacaceae) From Nicaragua. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 74:919-922.

Available online:

www.jstor.org/stable/2399461?seq=1

- n.d.

- Capitulo XCVI Del Segundo Cacahoaxochitl o flor de cacahoatl. Page 921-922.

- n.d.

- Guia Terapeutica para el Manejo de la Esquiozofrenia. Page 109.

Available online:

www.apalweb.org/docs/esquizofrenia2.pdf

- 1986

- Quararibea Aubl. s.l. (Bombacaceae) in Mexico, Central America and the Antilles: a taxonomic study. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison. 464 pages.

- 2004

- Plants of the Petén Itza’ Maya. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan Memoirs, Number 38. 248 pages.

- 2000

- Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Belize: With Common Names and Uses. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden Vol. 85. 246 pages.

Quararibea funebris and Quararibea yunckeri are listed on page 68. No use whatsoever given for Quararibea yunckeri.

Available online:

www.amazon.com.mx/Checklist-Vascular-Plants-Belize-Common/dp/0893274402

- 2015

- Messages from the Gods: A Guide to the Useful Plants of Belize. The New York Botanical Garden, Oxford University Press.

No mention of any medicinal use or any other use besides as a swizzle stick to produce foam in your cacao cup (p. 374).

Available online:

www.amazon.es/Messages-Gods-Useful-Plants-Belize/dp/0199965765

- 2012

- El Cacao como medicamento en las recetas y remedios novohispanos. Siglos XVI al XVIII. Tesis de maestria en Historia. Facultad de Filosofia y Letras. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Pages 11, 34 y 36.

- 2012

- Caracterizacion Bromatologica y Fisicoquimica de Tejate. Universidad de Guanajuato. Division Ciencias de la Vida Campus Irapuato-Salamanca.

- 2005

- Biodiversidad del Estado de Tabasco. CONABIO, UNAM, Mexico. 370 pages.

- 2016

- The forest of the Lacandon Maya: an ethnobotanical guide. Springer. 334 pages.

Available online:

www.springer.com/la/book/9781461491101

- 2003

- Árboles de Centroamérica: un manual para extensionistas. Oxford Forestry Institute, CATIE (OFI-CATIE)

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/260188536_Arboles_de_Centroamerica_un_Manual_Para_Extensionistas

- 2013

- Informe preliminar de vegetación del Parque Nacional Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo. En Anexo III del Diagnóstico del Plan Maestro del Parque Nacional Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo. Guatemala: CATIE-GITEC.

50% of the references name her Karla; the other 50% name her Carla.

- 2011

- Estudio etnobotánico de los principales mercados de Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, México. LACANDONIA, año 5, vol. 5, no. 2: 21-42, diciembre de 2011.

- n.d.

- Las plantas mágicas y la conciencia visionaria. Arqueologia Mexicana. Page 22.

Available online:

www.academia.edu/8421677/LAS_PLANTAS_M%C3%81GICAS_Y_LA_

CONCIENCIA_VISIONARIA

- 1992

- Cultivos marginados otra perperctiva de 1492. Production y proteccion vegetal No. 26. Pages 12 y 43. FAO- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación.

Available online:

www.fao.org/3/t0646s/t0646s.pdf

- 1999

- Nueva Especie y Notas al Genero Quararibea (Bombacaceae). Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc., 23 (Suplemento especial): 49-52, 1999.

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/262902996_Nueva_especie_y_notas_al_

genero_Quararibea_Bombacaceae

- 2007

- Plantas Nativas y Ecosistemas Relacionados al Tejate, una Bebida Tradicional de Oaxaca, México. Instituto Tecnológico del Valle de Oaxaca. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Mesoamericana 1 (3). 146 pages.

- 2012

- Estudio Fenológico de Quince Especies Arbóreas Relacionadas con la Alimentación de Fauna Silvestre en el bosque tropical lluvioso de Yaxhá, Petén. Thesis, USAC. 92 pages.

Helpful information on when 15 trees at Yaxha flower and fruit. But Quararibea is not one of them.

- 2000

- Hura crepitans L., Molinillo, jabillo, sandbox. USDA Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry. Pp. 270-274.

Available online:

https://rngr.net/publications/arboles-de-puerto-rico/hura-crepitans/at_download/file

- 2005

- Elsevier's Dictionary of Trees: Volume 1: North America. ELSVIER. 1493 pages.

Available online:

www.amazon.es/Elseviers-Dictionary-Trees-North-America/dp/0444517847

- 2011

- Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. Wiley. 1000 pages.

Wow, 1000 pages.

- 2014

- Producción de Espuma en el Chocolate con el Molinillo Tradicional. Revista digital universitaria –UNAM-.

Available online:

www.revista.unam.mx/vol.15/num5/art37/

- 2012

- Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 1, Fruits. Springer. 835 pages.

- 2011

- Árboles de México. Editorial Trillas. 368 pages.

- 2002

- Caracterización del Uso Tradicional de la Flora Espontanea en la Comunidad Lacandona de Lacanha, Chiapas, México. Interciencia vol. 27No. 10. Pages 517.

- 1937

- The Vegetation of Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publ. 478. Washington. 244 pages.

- 1938

- Plants Probably Utilized by the Old Empire Maya of Petén and Adjacent Lowlands. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 24, Part I:37-59.

- 2012

- El Huerto Familiar del Sureste de México. Secretaria de Recursos Naturales y Protección Ambiental del Estado de Tabasco. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. Page 85.

- 2010

- Farmacia Viviente: conceptos, reflexiones y aplicaciones. Programa Universitario de Medicina Tradicional y Terapéutica Naturista. Departamento de Fitotecnia, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Page 60.

- 2008

- Tamizaje fitoquímico de la especie vegetal guatemalteca Quararibea yunckeri Standley Subsp. izabalensis W.S. Alverson ex Véliz (Bombacaceae). Thesis, USAC, Guatemala. 64 pages.

Available online:

http://biblioteca.usac.edu.gt/tesis/06/06_2698.pdf

- 2015

- Las Flores Comestibles. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Page 252.

- 2008

- Trees of Guatemala. The Tree Press. 1033 pages.

Page 104.

- 2011

- Árboles del Mundo Maya. Museo de Historia Natural de Londres, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Universidad del Valle and Propetén de Guatemala and Belize Forest Department.

Helpful book; contributing authors are experienced botanists. They cover 220 species of trees, more than virtually all other “Books on Trees of the Maya.” Even include tasiste (which is missing from all other books on “Trees of the Maya” except for the recent book on Árboles de Calakmul.

But if all this effort is going into a book, would help if there were more photos, larger photos, and not so much blank space at the bottom of each page. Plus would help if the text could include personal first hand experience with these trees out in the Mundo Maya. But even as is, it is a helpful book.

If you are doing field work you need this, plus Árboles de Calakmul, plus Árboles tropicales de México. Parker’s book you need back in your office, since out in the field it’s not much help due to lack of photographs. Back in your office the books by Regina Aguirre de Riojas are also helpful.

- 1968

- Arboles tropicales de Mexico. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Mexico, D.F. 413 pages.

- 2005

- Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principals especies. 3rd edition. UNAM, Fondo de Cultura Economica. 523 pages. This book is a serious botanical monograph. 1968 was the first edition (I still have this), 1998 was second edition. The 3rd edition is a “must have” book. Each tree has an excellent line drawing of leaves and often flowers and fruits (though to understand flowers you need them in photographs, in full color). Each tree has a map showing where found in Mexico (such maps are lacking in most books on Trees of Guatemala or plants of Belize). But trying to fit a description of a tree on one single page means that a lot of potential information on flowering time is not present. And, this is definitely not a book on ethnobotany: for that you need Suzanne Cook.

- 1919

- Batido and other Guatemalan Beverages prepared from Cacao. American Anthropologist, N.S. 21: 403-409.

- 1983

- The phytochemistry of Quararibea funebris. Botanical Museum Leaflets 29 (2): 151-58.

- 1943

- Timbers of the New World. Arno Press.

- 1939

- American Woods of the Family Sapotaceae. Tropical Woods 59, 46-49.

- 2008

- Plant diversity assessment in the Yaxchilan Natural Monument, Chiapas, Mexico. Boletin de la Sociedad Botanica de Mexico, 83:53-76.

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/262589806_Plant_diversity_assessment_in_the_Yaxchilan_Natural_Monument_Chiapas_Mexico

- 1977

- An unusual spice from Oaxaca: The flowers of Quararibea funebris.Botanical Museum Leaflets 25 (7): 183-202.

- 1957

- The Genus Quararibea in Mexico and the use of its flowers as a spice for Chocolate. Botanical Museum leaflets, Harvard University. V. 17 1955-1957, Pp. 247-264.

- 1982

- Plantas de los Dioses. Fondo de Cultura Economica, Mexico.

Available also in English, German, and French.

- 1999

- A Classification and Ordination of the Tree Community of Tikal National Park, Peten, Guatemala. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 169-297.

Even though 20 years ago, it’s the best list of trees of Tikal that I have found. There is a web site with plants of Tikal but they are not separated into trees, vines, shrubs, etc., so harder to use. The new monograph on Arboles de Calakmul is better than anything available so far on Tikal (and the nice albeit short book by Felipe Lanza of decades back on trees of Tikal is neither available as a scanned PDF nor as a book on Amazon or ebay).

- 2004

- Plants of the Petén Itza’ Maya. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan Memoirs, Number 38. 248 pages.

Very helpful and nice collaboration with local Itza’ Maya people. But would help in the future to have a single index that has all Latin, Spanish, and English plant names all together so that you can find plants more easily.

Available online:

www.amazon.com/Plants-Peten-Itza-Maya-Anthropology/dp/0915703556

- 2008

- Food Globalization and Local Diversity. The case of Tejate. Current Anthropology. Volumen 49, Number 2, April 2008. Page 281.

- 2010

- Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Ancient Mesoamerica. Springer. 704 pages.

Available online:

www.amazon.com/Pre-Columbian-Foodways-Interdisciplinary-Approaches-Mesoamerica/dp/1441904700

- 1923

- Trees and Shrubs of Mexico. Contributions from the U.S. National Herbarium, Volume 23, Part 3. Smithsonian Institution.

- 1930

- Flora of Yucatan. Fieldiana, Botany Series, Vol. 3, No. 3. Field Museum of Natural History p. 354.

- 1949

- Flora of Guatemala. Volume 24, Part VI. Chicago Natural History Museum.

- 1958

- Flora of Guatemala. Vol. 24, Part I, Chicago Natural History Museum.

- n.d.

- Food, Foam, and Fermentation in Mesoamérica. University of Texas at Austin. Page 9.

- 2008

- Mesa de Flores, Missa de Flores. Os Mazatecos e o Catolicismo No México Contemporáneo. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. 108 pages.

- 2000

- Subespecie nueva de Quararibea (Bombacaceae) de Guatemala. Anales del Instituto de Biologia Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, Serie Botanica 71(2):81-85, 2000.

- 2002

- Homegardens of Maya Migrants in the District of Palenque (Chiapas/Mexico): Implications for Sustainable Rural Development. In: Stepp, J.R., Wyndham, F.S., and R.K. Zarger (eds.). Ethnobiology and Biocultural Diversity. Pp: 631 – 647. University of Georgia Press; Athens, Georgia.

- 1990

- Funebradiol, a New Pyrrole Lactone Alkaloid from Quararibea funebris Flowers. J. Nat. Prod., 1990, 53 (6), pp 1611–1614

- 2009

- Sacred Giants: Depiction of Bombacoideae on Maya Ceramics in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Economic Botany, 63(2), 2009, pp. 119–129.

Available online:

https://biosurvey.ou.edu/download/publications/ZidarElisensEB09.pdf

Acknowledgements

We thank biologist Licda. Mirtha Cano, Parque Nacional Tikal, for encouraging FLAAR to devote our camera equipment, our experienced team, and our time and energy to creating a photographic archive of the flora and fauna of Tikal. As soon as we can find more molinillo trees at Tikal and find more flowers, we will return to do additional photography.

We appreciate the hospitality of the park administration and show here the logos of the institutions which support the Parque Nacional Tikal. We also appreciate the patience and knowledge of the two local assistants of the team of Mirtha Cano.

We thank Nolasco, a knowledgeable local person, for telephoning us when Quararibea funebris was blooming near his house.

We thank Rejina de Riojas for providing access to both her tree rescue properties in Guatemala.

Helpful web sites for any and all plants

There are several web sites that are helpful even though not of a university or botanical garden or government institute.

However most popular web sites are copy-and-paste (a polite way of saying that their authors do not work out in the field, or even in a botanical garden). Many of these web sites are click bait (they make money when you buy stuff in the advertisements that are all along the sides and in wide banners also. So we prefer to focus on web sites that have reliable information.

https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/neotrop/plantae/

Neotropical Flora data base. To start your search click on this page:

https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/neotrop/plantae/collections/harvestparams.php

Unfortunately this international botanical data base has only four specimens listed. Separately, I have found about five trees so far: get into a 4-wheel drive vehicle, drive to remote areas, ask local people, or often pure coincidence seeing one in flower along the side of the “road” that you are doing your best to get your 4WD pickup truck through.

http://legacy.tropicos.org/NameSearch.aspx?projectid=3

This is the main SEARCH page.

https://plantidtools.fieldmuseum.org/pt/rrc/5582

Another SEARCH page for herbarium specimens, in this case limited to The Field Museum (Chicago).

http://enciclovida.mx

CONABIO. The video they show on their home page shows a wide range of flowers pollinators, a snake and animals. The videos of the insects are great.

www.kew.org/science/tropamerica/imagedatabase/index.html

Kew gardens in the UK is one of several botanical gardens that I have visited (also New York Botanical Gardens and Missouri Botanical Gardens (MOBOT), in St Louis. Also the botanical garden in Singapore and El Jardín Botánico, the open forest botanical garden in Guatemala City).

www.ThePlantList.org

This is the most reliable botanical web site to find synonyms. In the recent year, only one plant had more synonyms on another botanical web site.

Web sites specifically on Quararibea funebris

https://alchetron.com/Quararibea-funebris

Outstanding photographs of the flowers of Quararibea funebris. The depth of field is better than I have seen anywhere. All the photographs are cited as being borrowed from www.TopTropicals.com.

www.backyardnature.net/mexnat/quararib.htm

A few photographs and introductory information.

Bibliography part II: Web pages with helpful material on Quararibea funebris – Molinillo

http://toptropicals.com/html/toptropicals/plant_wk/quararibea.htm

Excellent description and ample discussion.

http://legacy.tropicos.org/NameSearch.aspx?projectid=3

This is an essential botanical web site. Yet Not one single location of one single specimen anywhere in Mesoamerica or anywhere else. The map is totally empty.

www.cuexcomate.com/search?updated-max=2013-04-26T05:00:00-07:00&max-results=10

www.exploringoaxaca.com/gastronomy,oaxaca,tejate/

https://nuevomundo.revues.org/617

https://toptropicals.com/catalog/uid/quararibea_funebris.htm

Several really good photographs of the flowers, plus photos of young trees still in flower pots. But zero bibliography.

http://zoom50.wordpress.com/2012/01/05/rosita-de-cacaofuneral-treequararibea-funebris/

Nice photo of Quararibea funebris showing flower, seed pod, on leaf. Plus mentions use still today in Oaxaca. But has no bibliography whatsoever.

Field Museum of Natural History, Pub. 350, Botanical Series Vol. XII.

http://biblio3.url.edu.gt/Libros/2011/etGuate/7.pdf

http://www.arbolesdecentroamerica.info/index.php/es/species/item/download/168_5e49b4bf7d1f55ba7a8750f586fe645d

by Vivian Hurtado, FLAAR Mesoamerica

Previously updated July 2015, after one of our other photographers was able to photograph molinillo flowers on the Costa Sur of Guatemala.

Most recently updated 2020

First posted April 29, 2013.