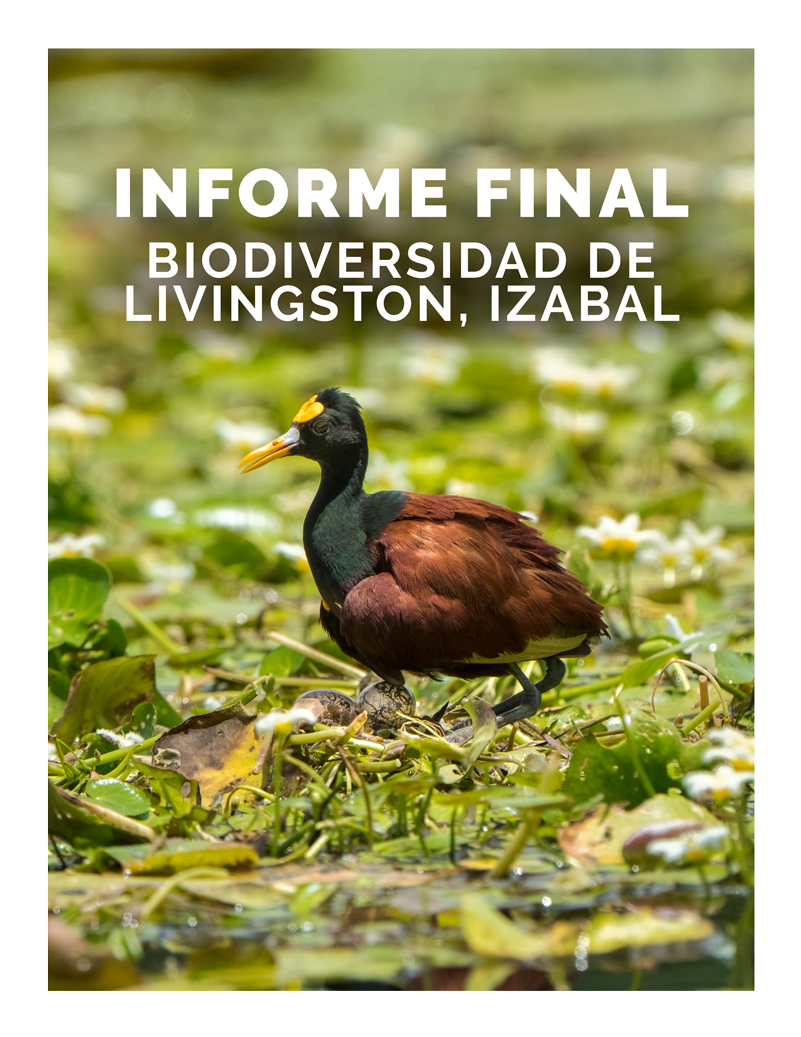

In March of 2023 our expedition team found and documented mangrove trees along Rio San Pedro, and this has been an exciting finding for our team! This mangrove remnant is remarkably unique, as well as its evolutionary history.

Mangroves have bright green leaves and characteristic aerial roots. Photo by: Vivian Hurtado. Rio San Pedro, March, 2023.

We first got to learn about these mangrove remnants through a series of media publications related to a research project in Mexico (this is Aburto-Oropeza et al. 2021’s study which will be cited later on this note). The researchers of this project located and sequenced various mangrove populations scattered inland throughout the Yucatan peninsula, including some important remnants in the basin of Rio San Pedro. Moreover, some of the highlights of this study include the documentation of a mangrove forest that is located 170 km inland from the Atlantic ocean.

Given that the researchers also mentioned the existence of isolated mangroves in the Guatemalan portion of Rio San Pedro, we decided to start investigating this topic. In that sense, we were able to find that the presence of mangroves in this area had already been discussed in at least two publications, one by Bestelmeyer and Alonso (2000) and the other by Castellanos (2006). We also looked at satellite images of this area, and we found that most of the river's basin is already deforested. So the only chances of finding mangroves would be by asking local people and navigating the river.

Mangroves have bright green leaves and characteristic aerial roots. Photo by: Vivian Hurtado. Rio San Pedro, March, 2023.

Later on, by the request of Mirtha Cano (biologist and administrator of one of the protected biotopes located next to Rio San Pedro) we planned an expedition to Rio San Pedro and Rio Escondido for another documentation project. However, to make the most of this expedition, we started asking local people if we could find the mangroves of Rio San Pedro. And indeed, we found that it was possible to get to some mangrove trees by navigating up river from El Naranjo village, so we did the proper planning to look for the mangroves in the same expedition.

Later on the actual trip, the expedition team did find the mangrove trees, and photographed them. Since then, the team has learned a lot about these mangroves' history and ecology. According to Aburto-Oropeza et al. (2021) these mangrove remnants first got here 120,000 years ago, because of a higher level of the sea. Nowadays, they still survive here because there is a high concentration of calcium in Rio San Pedro. If it was not for the leakage of calcium to the river (from the karstic soils that surround it), these mangroves wouldn't still be growing here. In fact, mangroves are coastal species that grow only on brackish water, with mangroves of Rio San Pedro being an amusing exception.

Mangrove propagule (still attached) collected at Rio San Pedro. Photo by: Vivian Hurtado. Rio San Pedro, March, 2023.

We are currently finishing a PDF report with the photographs of this expedition and helpful data that may assist you, if you are a student or researcher, to learn more about these remarkable mangroves. We hope that our work and the documentation we are doing with these mangroves can encourage you, and the local authorities to study and protect these mangroves. As mentioned before, most of the river basin is deforested and only a few vegetation patches persist, so the risk of losing these mangroves is alarmingly high.

We are planning a second expedition to this area later on this month and we encourage you to look in the next few weeks for the PDF on these mangroves and other ecosystems of the same area.

Bibliography on mangroves from Rio San Pedro

- 2021

- Relict inland mangrove ecosystem reveals Last Interglacial sea levels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021. Vol. 118, No. 41. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024518118

Note: This is Aburto-Oropeza et al. ambitious study. They even found another mangrove species, Conocarpus erectus, in the inland mangrove associations from Tabasco, as well as other plant species from coastal mangrove associations.

- 2000

- Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Belize: With Common Names and Uses. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden Vol. 85. 246 pages.

- 2015

- Messages from the Gods: A Guide to the Useful Plants of Belize. The New York Botanical Garden, Oxford University Press.

- 2000

- A Biological Assessment of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala. RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment 16, Conservation International, Washington, DC. 221 pages.

Free download:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303882937_An_ichthyological_s

urvey_of_Laguna_del_Tigre_National_Park_Peten_Guatemala

Note: Rhizophora mangle is mentioned in pages 15 and 37, as being

present and outside of Laguna del Tigre National Park (which increases

the risk of these mangroves not being protected).

- 2005

- Biodiversidad del Estado de Tabasco. CONABIO, UNAM, Mexico. 370 pages.

- 2000

- Rhizophoraceae de la Península de Yucatán (Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán: Sostenibilidad Maya, 2000).

- 2006

- Plan Maestro Parque Nacional Laguna del Tigre y Biotopo Laguna del Tigre-Río Escondido. Guatemala. Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas – CONAP. Alianza Kanteel. Wildlife Conservation Society. 24 pages.

Note: The existence and location of mangroves is mentioned in pages 31 and 34.

- 2009

- Plantas Comestibles de Centroamérica. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio). Santo Domingo de Heredia. Costa Rica. 360 pages.

Available Online: www.museocostarica.go.cr/descargas/PlantasComestiblesCA-VE.pdf

- 2022

- Sediment depth and accretion shape belowground mangrove carbón stocks across a range of climatic and geologic settings. Limnol Oceanogr, 67: S104-S117. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12241

- 2010

- Indicadores ecológicos de la zona riparia del Río San Pedro, Tabasco, México. MS Thesis, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. 131 pages.

Free download: https://ecosur.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/101

7/1656/1/100000050585_documento.pdf

- 2013

- Legislación, cambio de uso de suelo y reforestación en manglares de Cárdenas, Tabasco [Doctoral thesis]. Mexico. Colegio de Postgraduados. 129 pp. http://hdl.handle.net/10521/2356

- 2016

- Cambios de uso del suelo en manglares de la costa de Tabasco. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agricolas Pub. Esp. No. 14. Pp. 2757-2767.

- 2005

- Structure of a unique inland mangrove forest assemblage in fossil lagoons on the Caribbean Coast of Mexico. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 13. Pp. 111-122. 10.1007/s11273-004-5197-x.

- 1937

- The Vegetation of Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publ. 478. Washington. 244 pages.

- 1938

- Plants Probably Utilized by the Old Empire Maya of Peten and Adjacent Lowlands. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 24, Part I:37-59.

- 2020

- An assessment of the spatial variability of tropical swamp forest along a 300 km long transect in the Usumacinta River Basin, Mexico. Forests. 2020; 11(12):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11121238

- 1967

- Mangrove Ecology and Deltaic Geomorphology: Tabasco, Mexico. Journal of Ecology. Vol. 55, No. 2. Pp. 301–343. https://doi.org/10.2307/2257879

- 1993

- Manglares de la Península de Yucatán. In: Salazar-Vallejo, S. and N.. González (comps.). Biodiversidad Marina y Costera de México. CONABIO and CIQRO. Pp. 660-672.k.

- 2021

- Rhizophora mangle from Yucatan. GitHub. https://github.com/zapata-lab/ ms_rhizophora. Deposited 9 June 2021.

- 2017

- Text

Written by Sergio D'angelo Jerez

Posted April 14, 2023