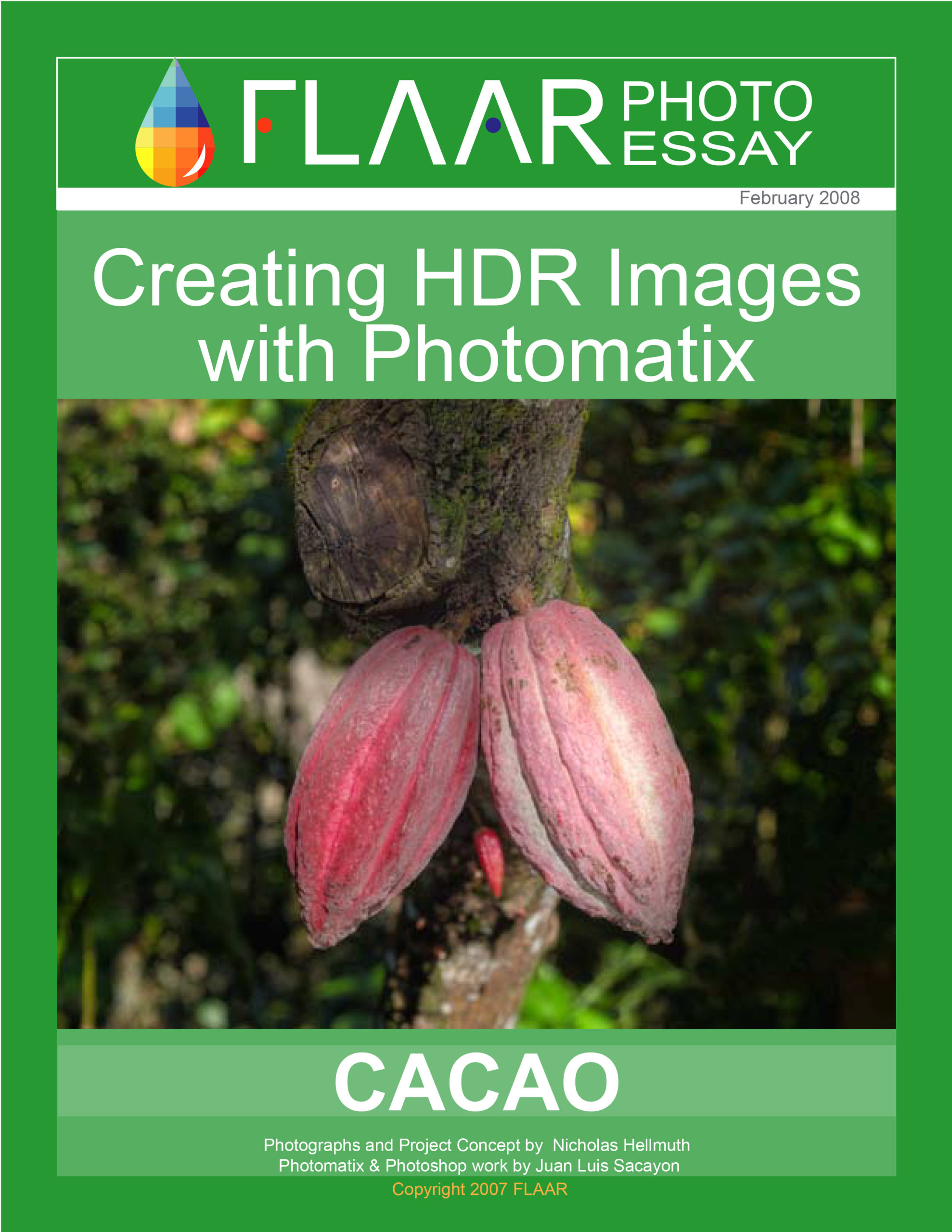

One of the best known sources of colorants for the ancient Maya is logwood. The Maya could use colorants from plants and cochinal insects to dye their cotton cloth, their bark paper (cloth), their henequen or other materials for clothing. For painting murals and painting buildings they had plenty of additional colorants from clay and minerals.

But many web sites and even some scholarly botanical monographs confuse the two types of the logwood tree. So this discussion seeks to point out to Mayanists to be careful in using the name Palo de Brasil when they really mean Palo de Campeche.

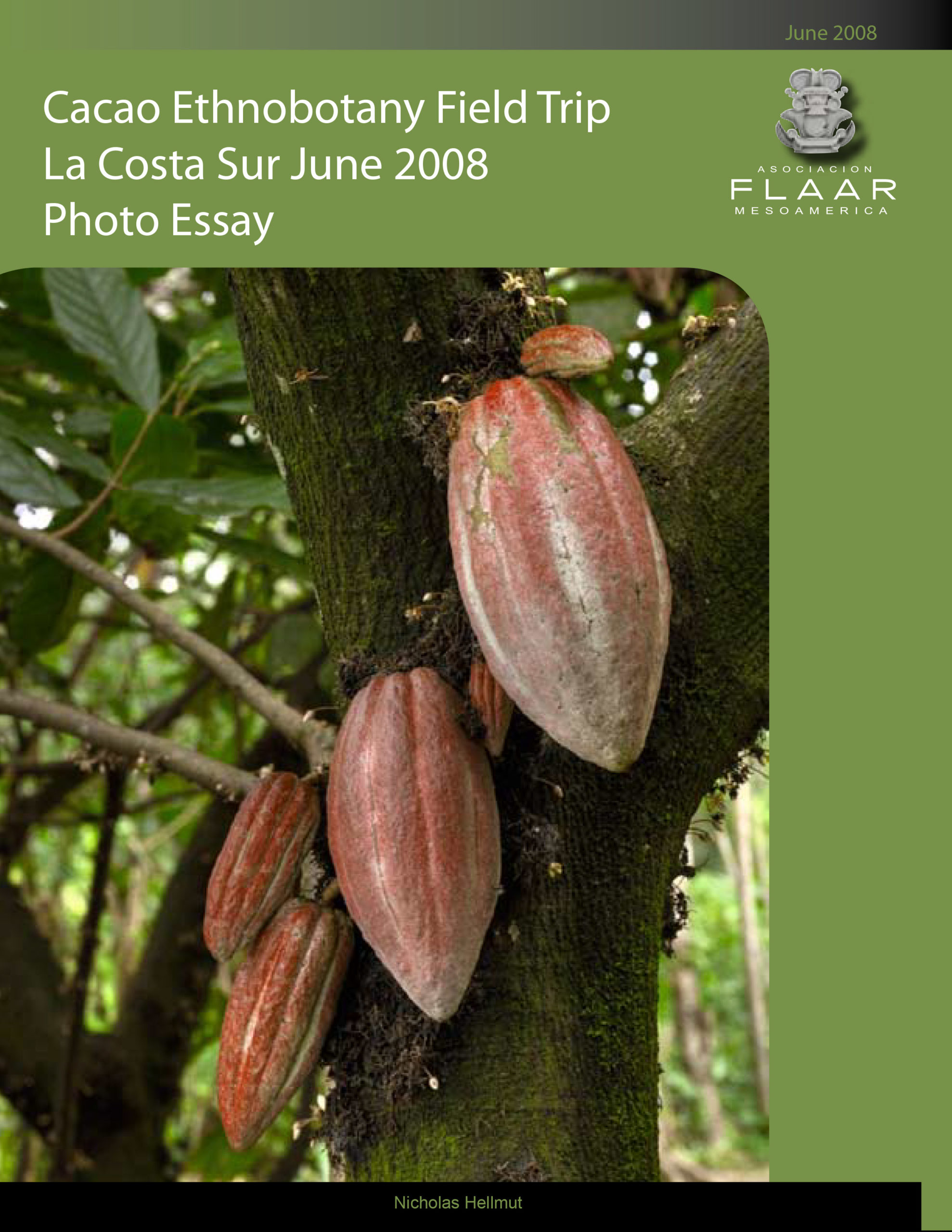

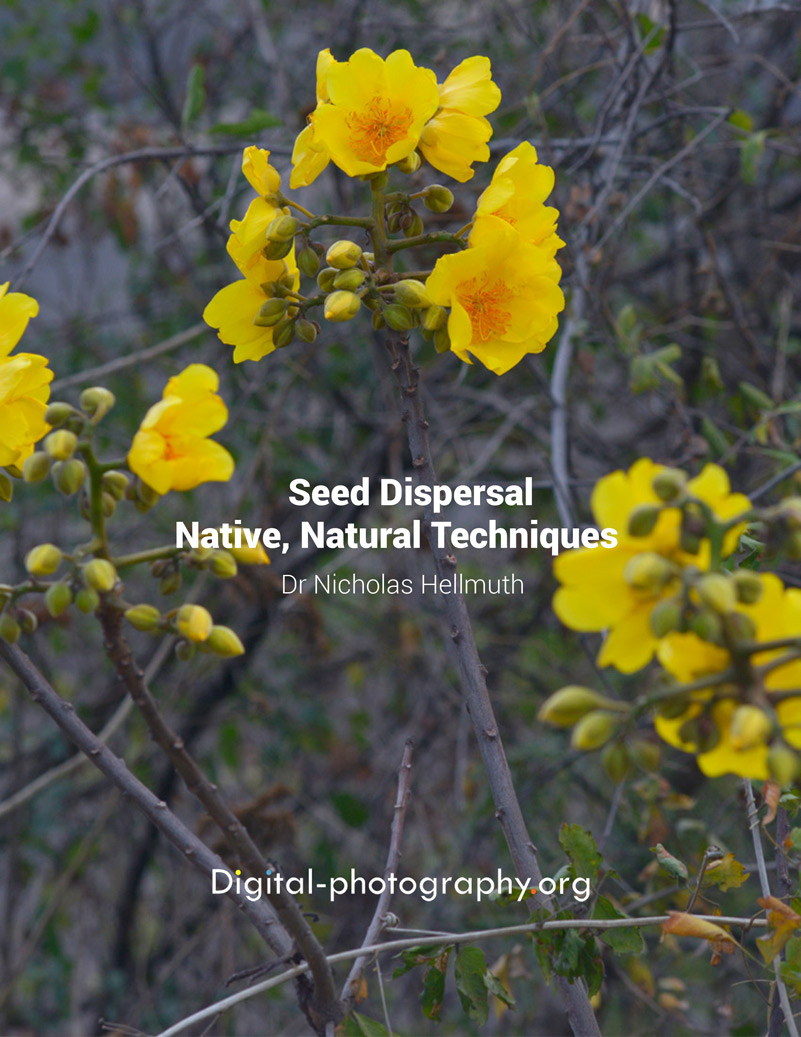

Palo de Brasil, Haematoxylum brasiletto, taken on January 2014.

Palo de Brasil and Palo de Campeche are two different species

- Haematoxylum campechianum is palo de Campeche.

- Haematoxylum brasiletto is palo de Brasil. This country is spelled Brasil in Spanish.

- These are two totally different species (but the gnarled trunk shape is almost identical):

- Haematoxylum brasiletto grows best in dry desert areas.

- Haematoxylum campechianum grows along rivers or in seasonal swamps. In other words, Palo de Campeche needs lots of water; Palo de Brazil prefers very dry areas (but where it does rain at least a month or so a year).

Where to find Palo de Campeche

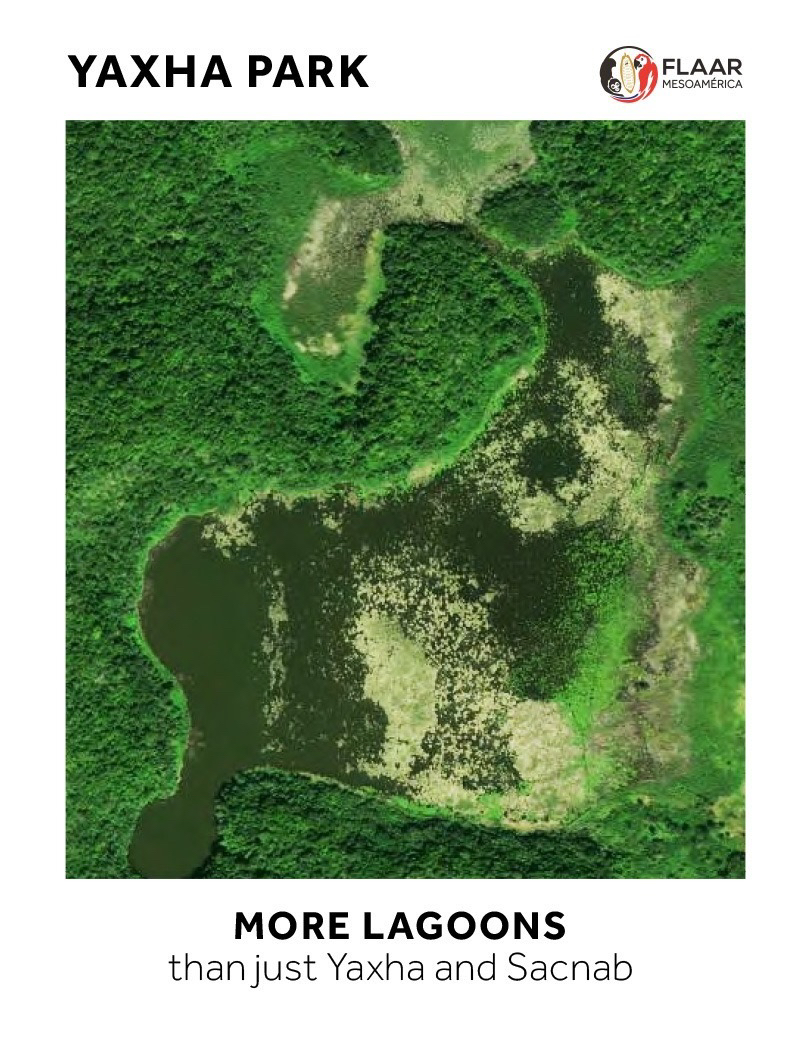

Palo de Campeche is found in many areas of El Peten and adjacent Campeche on the west and Belize on the east. Between Lake Yaxha and Lake Sacnab there is plenty of palo de tinto.

Lots of Palo de Tinto grows around Tikal. Just ask the guides. You can find Palo de Tinto along the road to Las Guacamayas (a biology research station near where the Rio San Pedro Martyr bubbles out of the ground).

There is Palo de Tinto along the Arroyo Petexbatun, Arroyo Pucte and along other tributaries of the Rio de la Pasion (but not along the large river itself; mostly on small tributaries).

These swampy rivers have no mangroves (mangroves are mostly near salt water). And mangrove swamps around Montericco do not have Palo de Tinto (at least not that I can remember).

In Mexico you can of course find palo de Campeche in Campeche. Plus along the Rio Lagartos, north-central coast of Yucatan (Jim Conrad, www.backyardnature.net). Abundant botanical articles by Mexican scholars list where else you can find it, such as Tabasco and Quintana Roo.

And correspondingly in Belize (which was founded by logwood cutters).

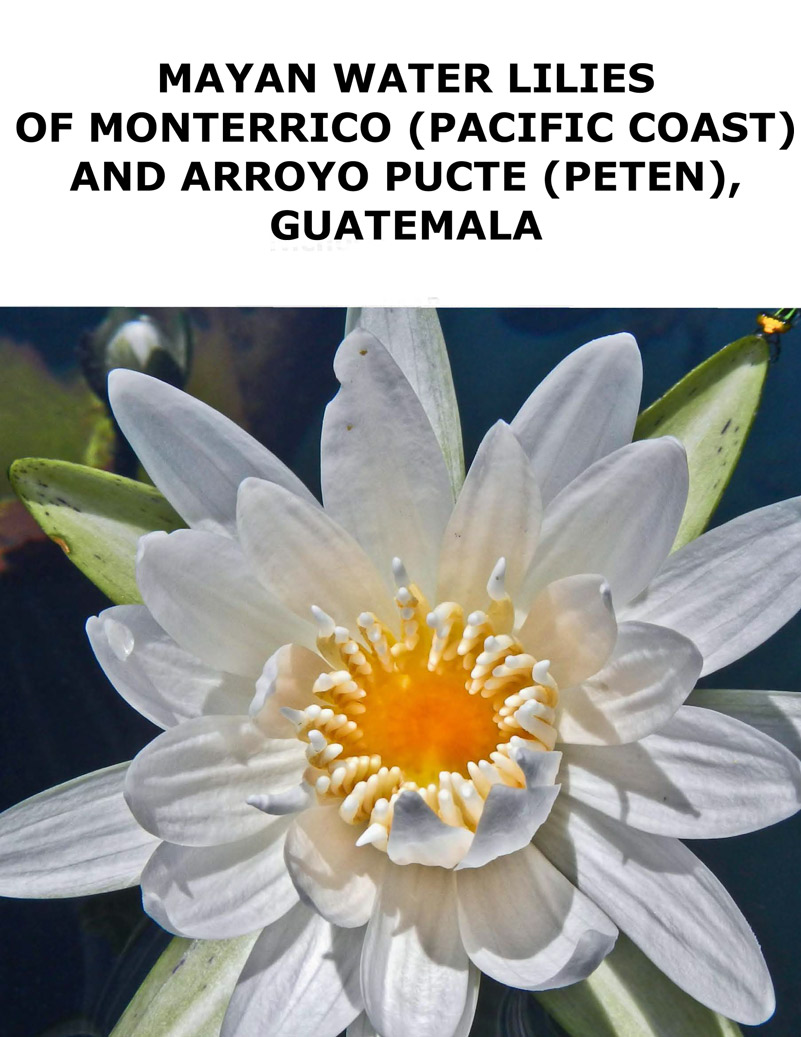

Palo de Campeche, Haematoxylum campechianum.

Where to find Palo de Brazil

From about km 65 to km 100 along the highway CA 9 from Guatemala City to Puerto Barrios you can find thousands of Palo de Brasil trees. Also along the turn off to the north (the highway from El Rancho towards Coban, Alta Verapaz). This highway has Palo de Brasil from El Rancho going up at least 10 km going north (at higher altitudes you begin to get pine and oak forests, and gradually no more Palo de Brasil).

Palo de Brasil, Haematoxylum brasiletto, taken on February 2013.

The type of soil or rock is very different for the two species

This eco-system overlooking the Motagua River is hilly, and rocky. Many Palo de Brasil trees grow from the rock cliffs or from the rock road-cuts (where the highway has cut through the mountain decades ago).

None of this is Karst; this is an area of completely different kind of rock. I do not believe any of this is limestone (though would want a geologist to comment further).

Palo de Campeche trees tend to grow on flat land; not on hills. Palo de Campeche tend to grow in soil, not on rock outcrops (no exception would surprise me, but where the two trees grow in Guatemala is about as different from each other as you can find. Plus this Peten area is generally limestone (but limestone hills are not where Haematoxylum campechianum grows.

Palo de Brazil blooms for many months

Palo de Brasil blooms for three months at least, maybe four or more. I can't claim every tree blooms that long, since we are driving along a 40 km stretch with hundreds and hundreds of trees. But we see most blooming for many months, December, January, February, March, and still into April.

Palo de Brasil, Haematoxylum brasiletto, taken on January 2014.

Palo de Campeche blooms only for a short period

Along any river whose banks are literally covered with logwood, almost never do you see flowers. It is my impression that Palo de Campeche blooms only a short period. We also need to check to see whether every individual tree blooms every year (I assume it does bloom every year, but Ceiba pentandra species do not whatsoever).

I was really surprised to find 1% of the logwood trees along the Arroyo Petexbatun blooming nicely the last week of March and first day of April.

Many books, articles, and web sites confuse the two trees

Both trees are called palo de tinto, though the correct one would be Palo de Campeche. Curiously even Lundell's 1937 book on vegetation of the Peten lists both species for El Peten. I estimate that the presence of Palo de Brasil in El Peten is highly unlikely, since Palo de Brasil is at home in the very very dry desert-like area along the hills overlooking the Rio Motagua. There are several species of cacti in the same areas. So I would not expect such plants in the seasonal rain forest area of El Peten. So I would suggest that botanists need to work out this situation and be sure that Palo de Brazil is not found in Peten, Campeche, Tabasco, or Belize.

The monograph by Suzanne Cook on ethnobotany of the Lacandon area of Chiapas is the best ethnobotanical study of this area so far. Her first edition also suggests both species are in her research area: Haematoxylon spp., H. campechianum L., H. brasiletto Karst. I would be very surprised to find Palo de Brasil in the Lacandon area of Chiapas. The second edition will remove the Palo de Brasil mention.

She documents the presence of Haematoxylon campechianum on the basis of

-Programa de Conservación y Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna

Nahá (2006)

-Nations and Nigh (1980)

-Nations (2006)

-Pennington and Sarukhan (2005) page 234, occurs from Tabasco and part of the Selva Lacandona (north east tip) up to the Yucatan peninsula, in low lands that are very clay susceptible to periodic or permanent flooding (translation by Suzanne Cook in personal communication to us as research for this web page, April 2015).

When you Google simply logwood, mexico the first and the third entries stick you (potentially incorrectly) with Palo Brasil.

This is typical: once one author lists something, scores of web sites (especially copy-and-paste sites) and dozens of Maya scholars simply use the same name. The best example of incomplete scholarship is Thompson's insistence on claiming that the Kin (sun) hieroglyph was based on the Plumeria flower. This claim, and most of what is written about Nikte among the Lacandon, varies from erroneous to totally misleading.

Even Wikipedia lists Haematoxylum brasiletto as Mexican logwood.

The otherwise excellent source, http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/monografia.php?l=3&t=&id=7910, claims palo Brasil "originaria del note de Granada…" Since this palo de Brasil tree is happily growing throughout the dry hills overlooking the Motagua River, I am assuming it is native to Guatemala (and to Mexico).

Osborne (1935:54) mentions brazilwood so Schevill, Berlo, Dwyer (editors) feature this (1996 edition, pp. 367 and 370). Brazilwood is Caesalpinia echinata; not either of the palo de tinto trees.

But beware, there are university web sites, even arboretum web sites, which confuse Brazilwood and Mexican logwood (http://apps.cals.arizona.edu/arboretum/taxon.aspx?id=704).

The most unexpected confusion between Palo de Brasil and Palo de Campeche is in Cyrus Lundell's otherwise excellent monograph on The Vegetation of Peten. On page 63 he clearly states that Haematoxylum brasiletto is "common in the central areas of swamp forest (tintal). He then lists Haematoxylum campechianum on the same page as "very common in central areas of swamp forest."

Although I am not a botanist, I am not convinced that both species are in the center of Peten area tintal seasonal swamps. But it is a challenge for me to say this, since Lundell worked in Campeche and adjacent El Peten for many years. He was a trained botanist as well.

For Tikal there is no scientific botanical documentation (that I yet know of) for Haematoxylum brasiletto. However it would be essential to have answers from Calakmul and from El Mirador. Ironically Haematoxylum brasiletto is clearly and specifically listed 8 km al noreste del ejido El Manantial, al noreste de Narciso Mendoza (Martinez and Galindo-Leal 2002:14). They call it tinto de montaña (http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/577/57707101.pdf).

Fortunately there is one web site which carefully describes and pictures all three trees:

- Brazilwood

- palo de Brasil

- palo de Campeche

(http://waynesword.palomar.edu/ecoph4.htm)

Palo de Campeche was used in temples, palaces, and tombs

In Classic Maya architecture

The most famous lintels in Maya palaces are of chico zapote wood. But I found vault beams of palo de tinto in the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar (Tikal Burial 196). And you can find other buildings of the Classic Maya with lintels of palo de Campeche. For example, the lintels of Santa Rosa Xtampak (Campeche) may be of various woods; more than just chico zapote.

Show the downloads, all volumes, of this Harvard thesis (several volumes).

Show the download of any Santa Rosa Xtampak reports

Palo de Tinto gets its name because it produces colors

Lots of books and articles are available which describe the colors which you can obtain from palo de tinto. During the Industrial Revolution in the UK, they brought in tons of palo de tinto from Belize.

First posted April 2015

After we were surprised to find palo de Campeche still blooming along the Arroyo Petexbatun, Sayaxche, El Peten, Guatemala. To study plants in this area, we recommend Julian and his Hotel Ecologico Posada Caribe. We have two web pages on this: here is the second page.