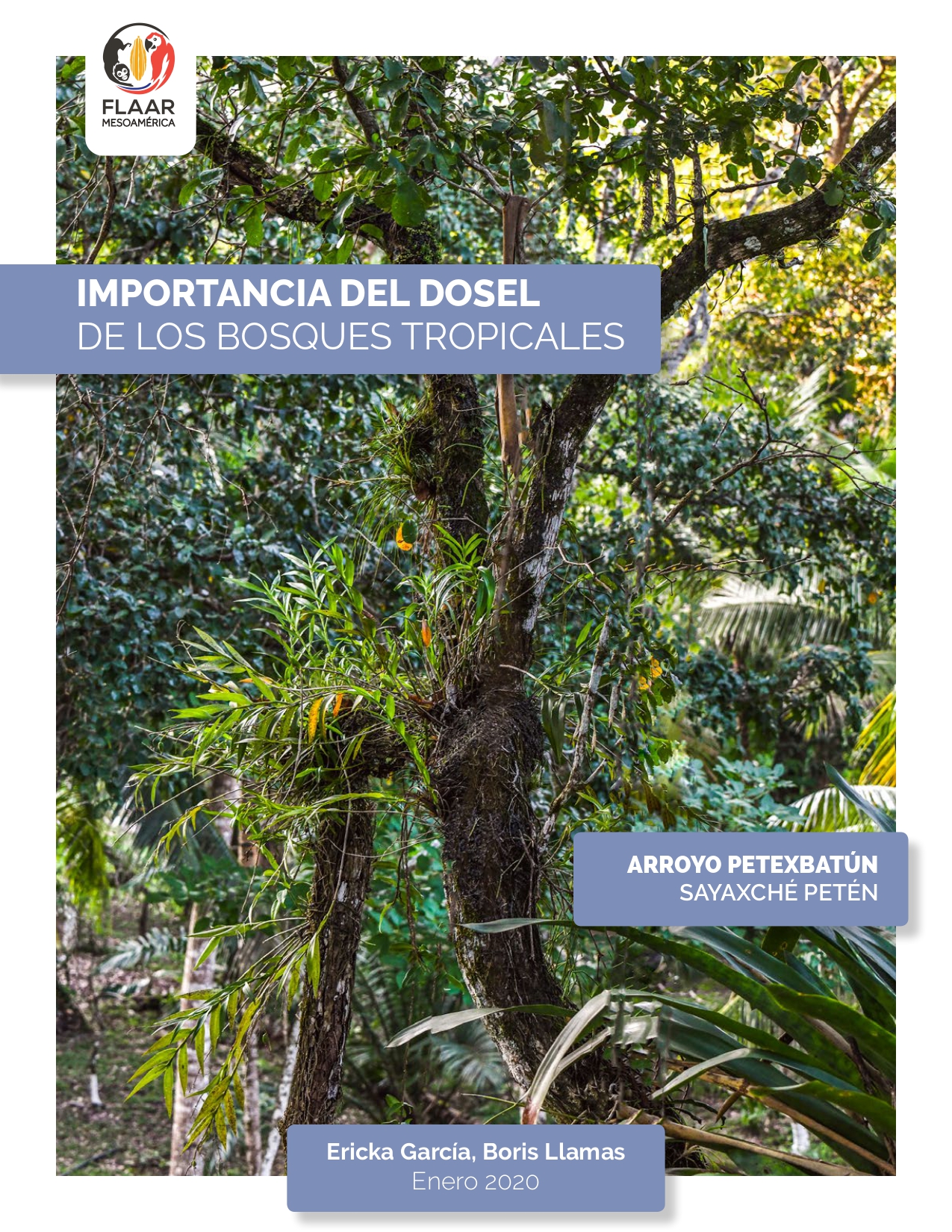

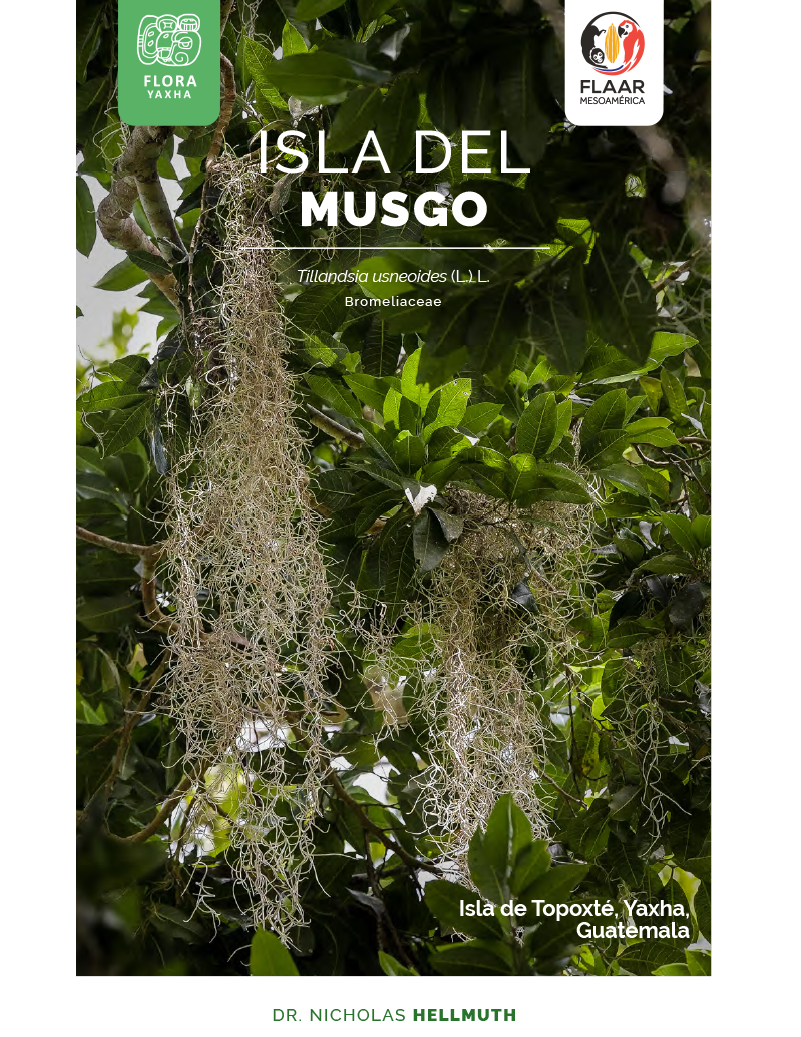

A single tree can have over 100 different species attached to it

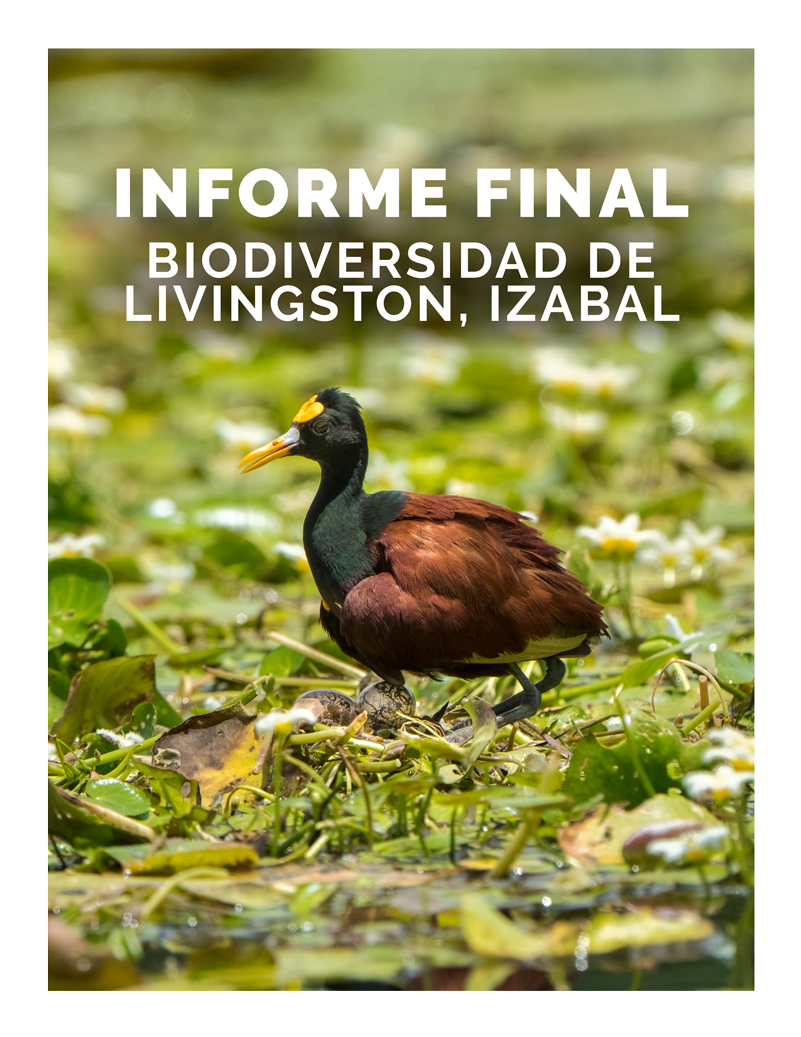

Look at any tree out in a rain forest (whether seasonally dry (like Peten) or wet much of the year (like Izabal) or with mist or rain most of the year (like parts of Alta Verapaz). You will see:

- Flat lichens on the trunks and 3-dimensional lichen up on branches,

- multiple species of vines climbing up the trunk.

- Moss in lots of places

- Liverworts

- Ferns of various species, sizes, and shapes, from truck to branches

- Bromeliads from tiny to tremendous in size and color

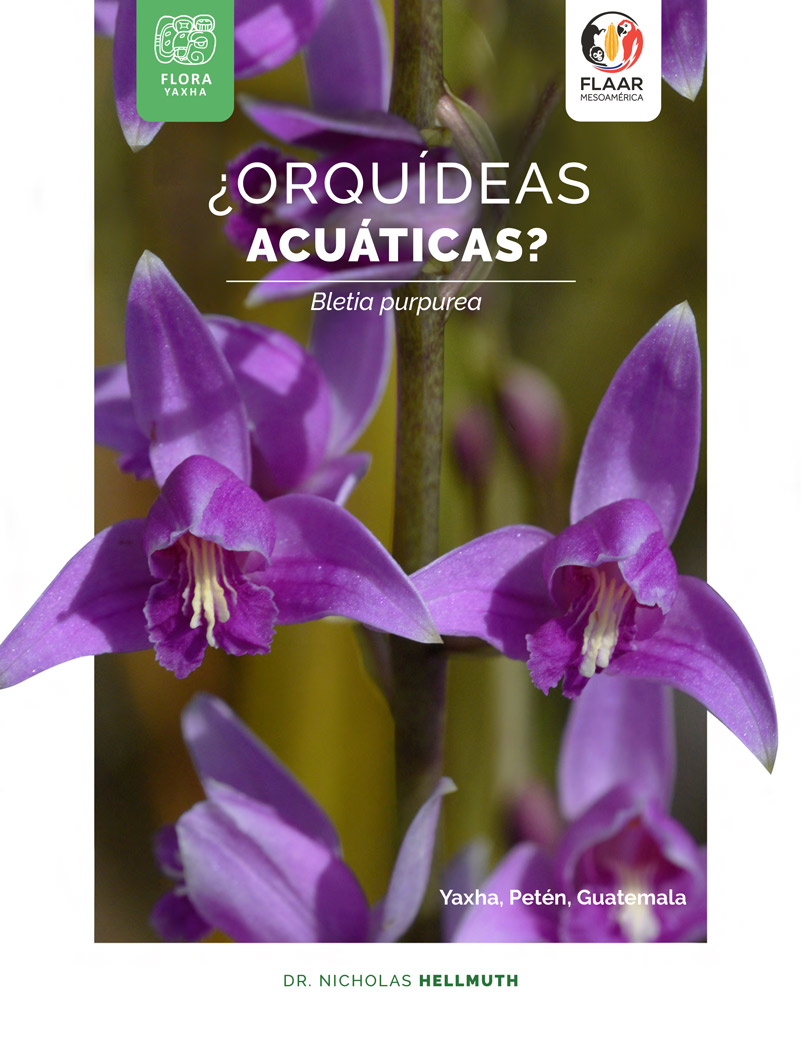

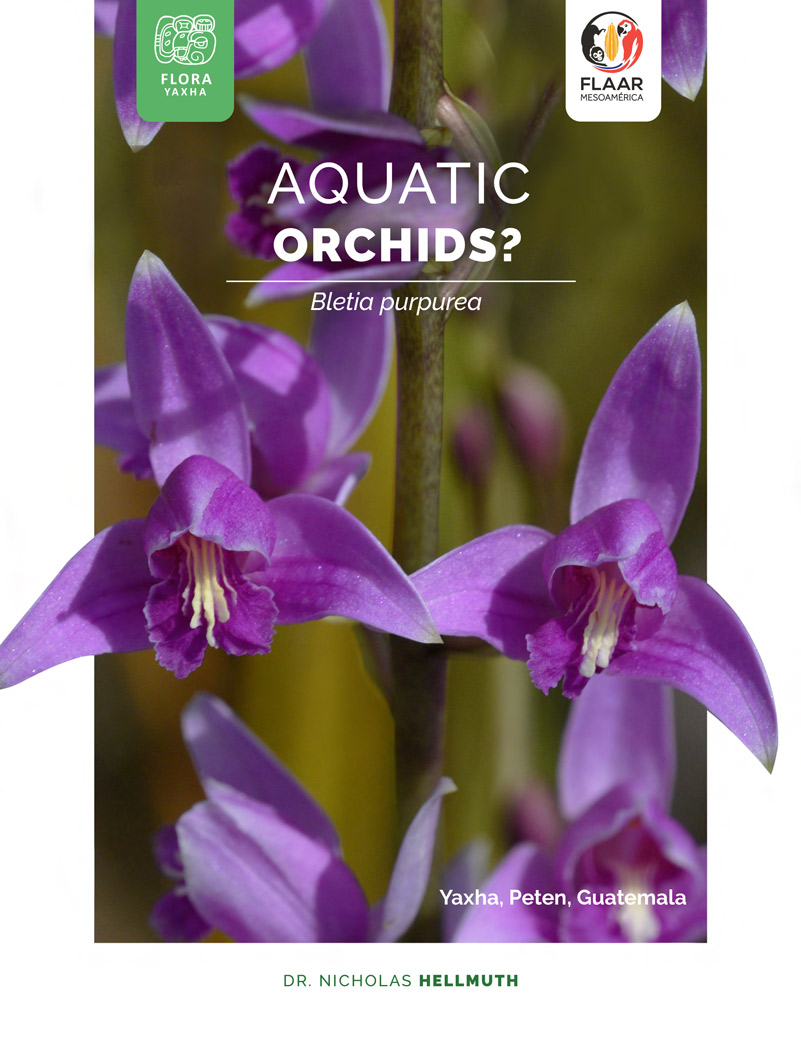

- Orchids of heavenly diversity

- Parasitic vines (especially high on the tree, to get sunshine)

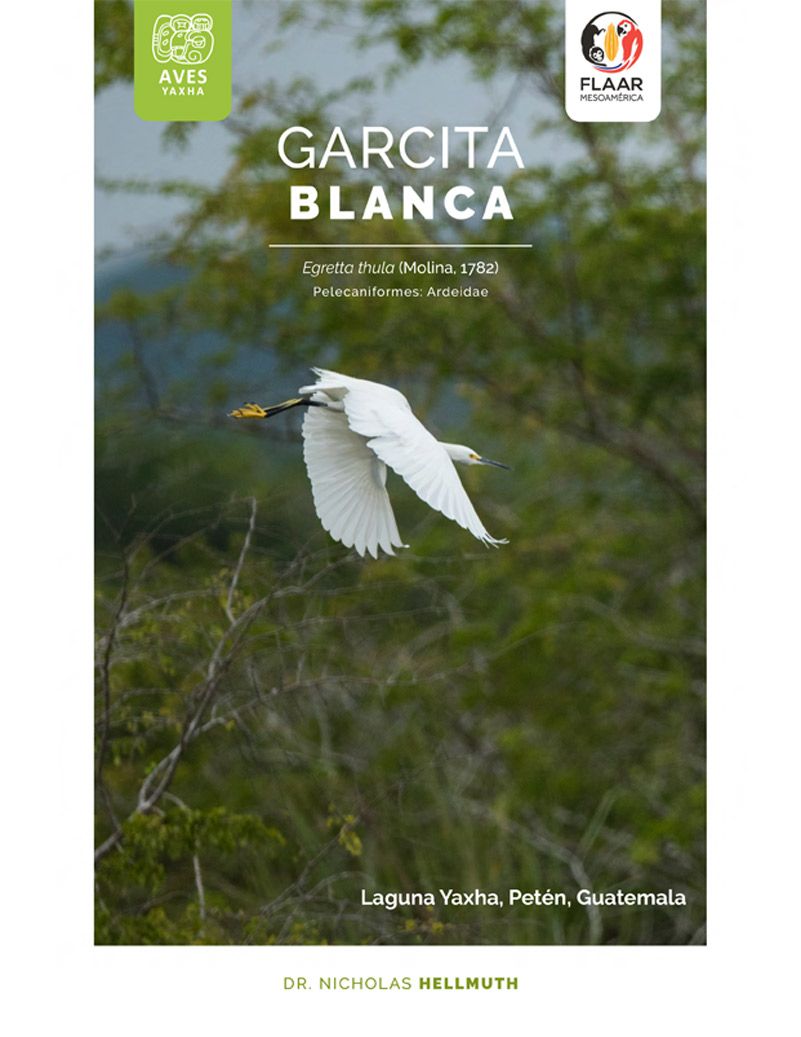

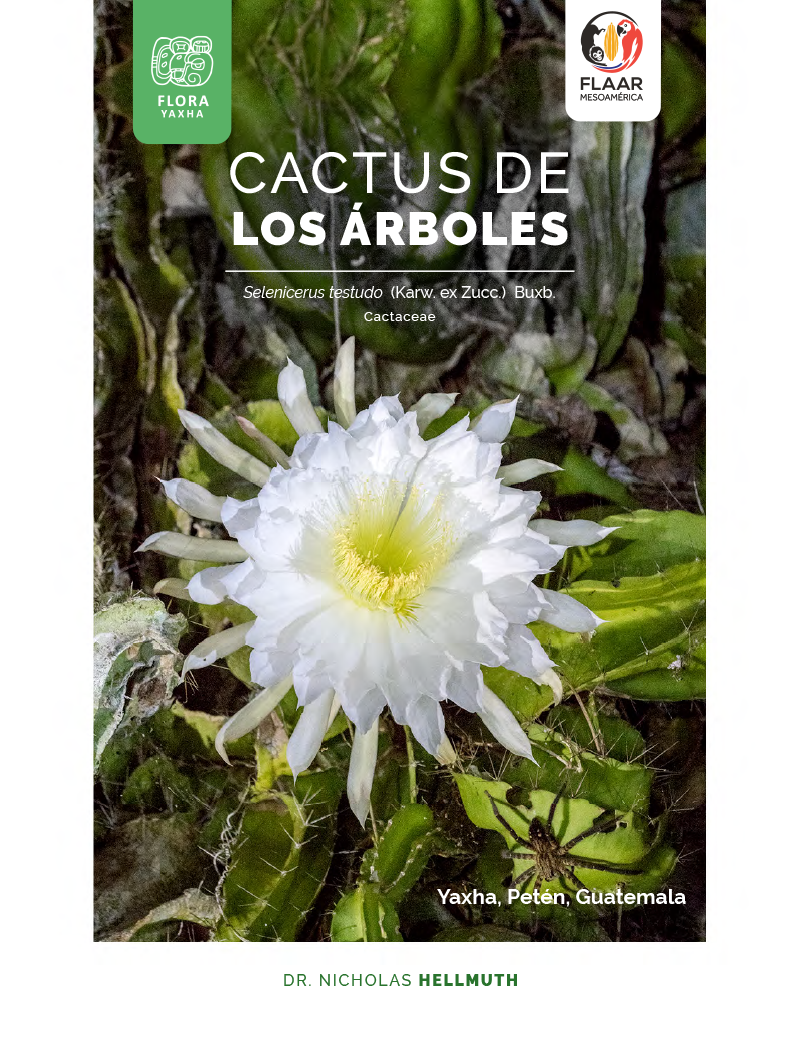

- Arboreal cacti, often cover much of the trunk and branches

On a large Ceiba, or large San Juan tree, or Conacoste, or Pucte tree, you could find easily 50 species of other plants on the trunks and branches (especially in the tree canopy). I prefer the word treetops since most of the plants are in the lower branches not the “canopy” across the top of the tree. I visualize the treetops as the total height and total width of everything once branches start.

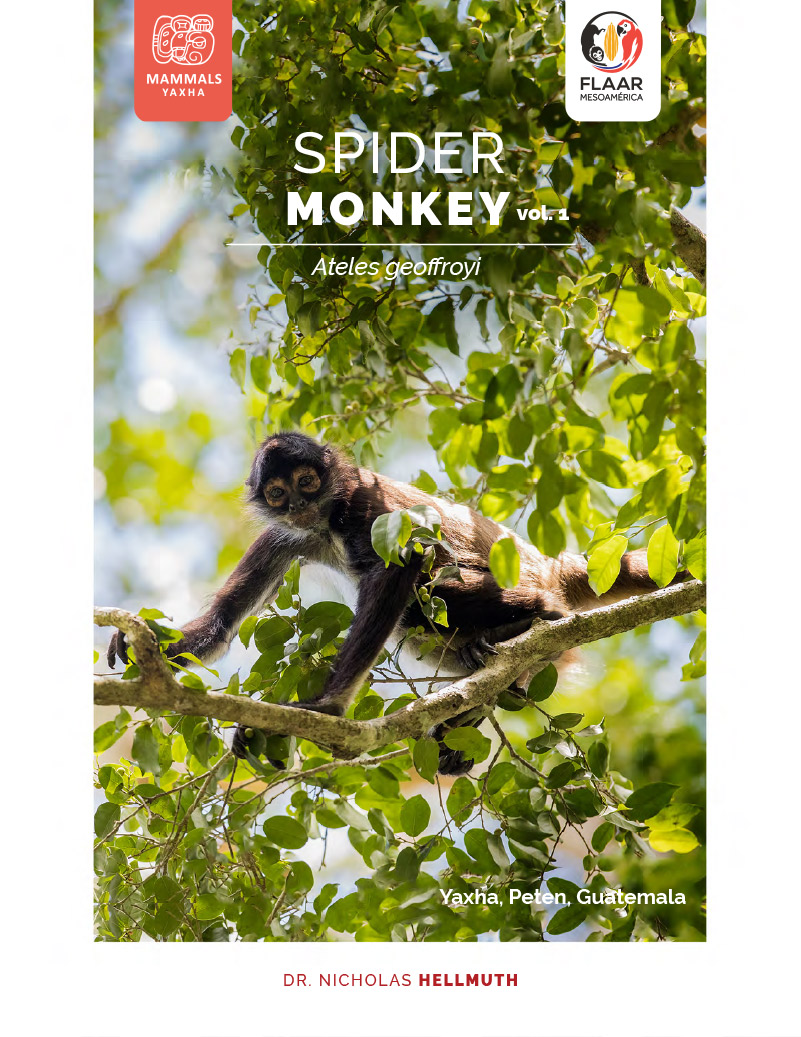

On some trees there could be as many as 100 species (especially if you count the lizards, arboreal frogs, and endless diversity of insects that make their home in trees). Any hollow tree has even more creatures living inside (including birds).

So, if you chop down one single tree, you destroy an entire ecosystem of over 100 species of flora and fauna.

This is our goal; to literally physically count the species (especially of moss, liverwords, ferns, lichen, bromeliads, orchids, arboreal cacti, vines, etc. that need trunks and branches and leaves for support or to collect nutrients. Only true parasites are truly parasitic (these often have gorgeous flowers).

Once we count all the species, we can prepare infographic posters in local Mayan, Xinca, and Garifuna languages to help teach the children: the children can then teach their parents and grandparents!

Treetops (tree canopy) are a paradise for orchids and bromeliads

The branches are the most populated parts of a tree. Rappelling is the way to get botany and zoology students up high so they can photograph and count the species.

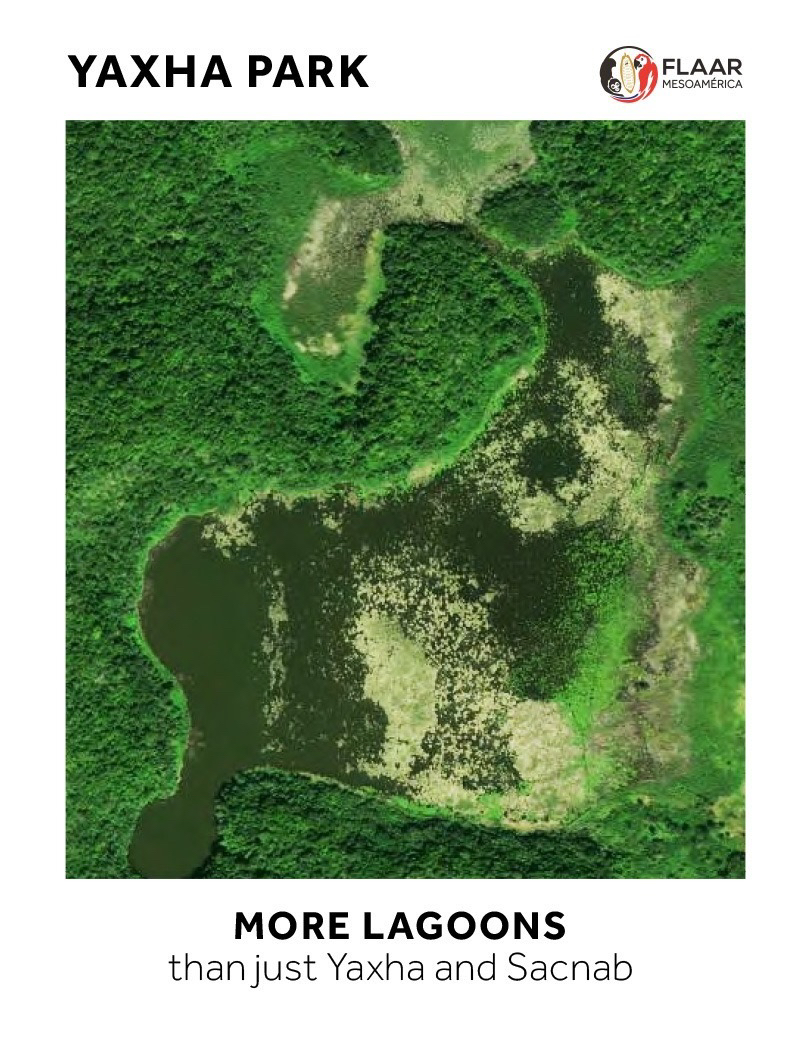

A drone is also helpful: a drone with a good camera can photograph the top (the literal canopy). But more important, a drone can photograph the branches. But a drone with cheap camera is useless: lenses are too wide-angle (thus distorted). Resolution is not high enough. GoPro are especially useless (we have tested four models of drones so far, so have initial experience).

A high resolution camera will produce images that make more impact are both local people and impact on potential donars.

Photo taken by a drone in Arroyo Faisan, Peten.

Tree Leaves come in diverse size, shape, and colors

When you are hiking through the forests, and the sun is shining down from above, the large tree leaves are beautifully back-lit.

Coccoloba leaves in Reserva Natural Tapón Creek, Área de uso múltiple Río Sarstún, Livingston, Izabal.

Many young tree leaves are copper-red in color. And of course, we all know the maple tree leaf that changes color in the autumn season. Even in Guatemala when hiking through the forests you see leaves of every color you can imagine. Indeed, some tree leaves are so yellow that from a distance it looks like the tree is in full bloom (but when you get closer you see the yellow are not flowers).

Tree leaves come in a remarkable diversity of size and shape. I have always wanted to create a photographic inventory of tree leaf size, shape, and color. Guatemala is a perfect place for this kind of project.

There is potential to find trees (such as Coccoloba) that have leaves large enough to make place mats and to press into forming a plate or platter (to sell to tourists who like eco-friendly products).

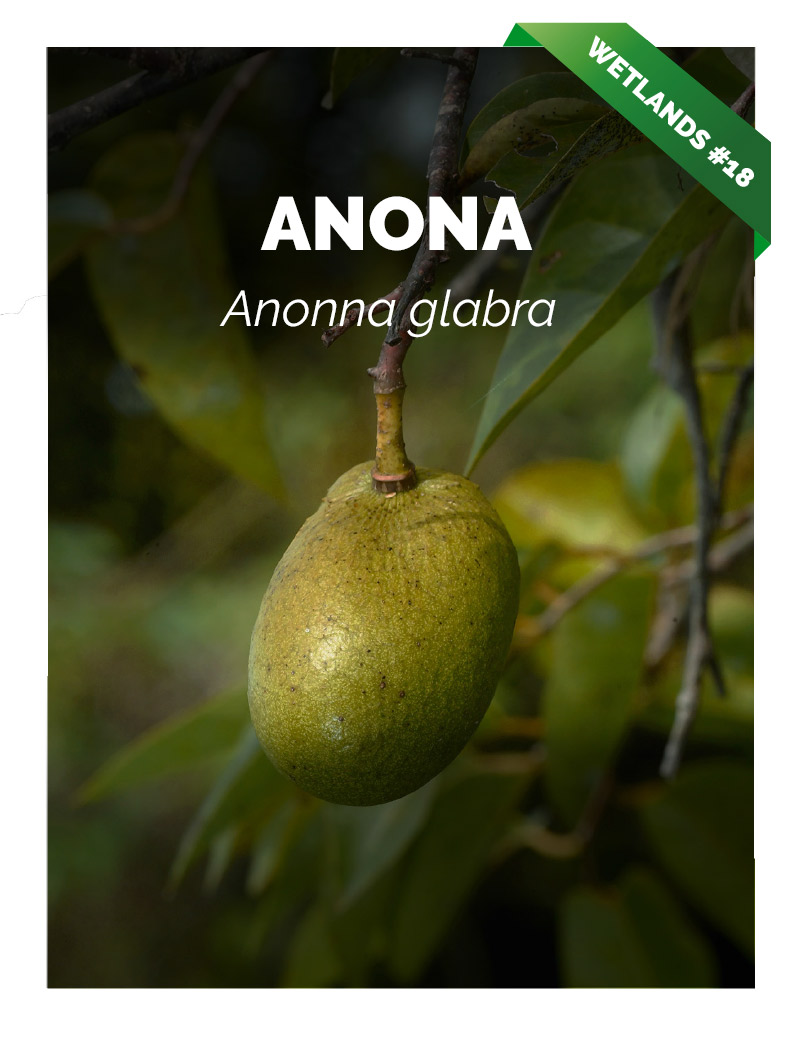

Some sources say the fruit can be eaten raw. Others say the fruit is cooked before being eaten, often stuffed with meat. In Aguacatan the ripe fruit is used to prepare sweets. It is reportedly eaten by pigs when available (Parker, 2008).

The tree is found in abundance on the dry hills between El Rancho and Salama, less frequently in other dry regions. Although it is widely cultivated in Guatemala, the trees are not very numerous since the fruit is generally not highly esteemed (Parker, 2008).

Tree Trunks are a complete ecosystem

Some trees have one mass of moss or lichen on one side; and other plants on the other side (or the other side is relatively empty). I have seen some masses of vines primarily on just one side of a tree. But other trees are covered completely (around all sides of the trunk). Tree trunks are a complete micro ecosystem, very biodiverse. You could easily do a MS thesis or PhD dissertation on plants and vines that grow on the trunks of corozo palms (especially in humid areas of Izabal, Peten, and Alta Verapaz).

Photo by Nicholas with the iPhone Xs in Reserva Natural Tapón Creek, Área de uso múltiple Río Sarstún, Livingston, Izabal.

Tree Bark is another topic of interest

The Preclassic stone stelae of Izabal (Chiapas, Mexico) show a “Crocodile tree.” This is most likely because some Neotropical trees of Mexico, Guatemala, etc. have a trunk with scaly bark and protrusions that looks like the scales of a crocodile or caiman (there is one species of caiman and two species of crocodiles in Guatemala). Several Maya vases also show crocodile trees. So I am very keen to find trees whose trunks look like the back of a crocodile. And if they have buttress roots, this would be the “head” of the crocodile. Several species of Genus Zanthoxylum are named palo de lagarto: Zanthoxylum kellermanii P. Wilson and

Peeling bark is noticeable on all species of palo de jiote and on unrelated pimiento gorda (allspice). This peeling bark is an attempt by the tree to make vines, moss, bromeliads, etc. fall off when the bark peels off. But I have found several palo de jiote trees in Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo that do have lichen on their trunks.

- Prickles, Spines, Thorns

Several kinds of trees in Belize are called prickly ash. Botanists call certain kind of sharp protrusions on a tree truck prickles. Many species of genus Vachellia have prickles. Several species of genus Zanthoxylum, family Rutaceae have them, but they are a bit flat (so not perfectly spherical). I prefer to call trunk thorns them conical spines if they are on a Ceiba aesculifolia (in dry areas) or on a Ceiba pentandra (mostly in seasonally wet areas). If on an acacia, I would tend to use the word thorn. But botanists have special words, though I notice not every botanist uses the concept prickle. To me a thorn is thinner and may be curved; to me a thorn is on a vine.

Some botanists also use the word conical spines even for Zanthoxylum (even though most are not as perfectly round in cross-section as are those of Ceiba species.

So there are lots of spiny aspects to tree trunks (especially Bactris (Huiscoyol) palms and escoba palms (Cryosophila stauracantha) and several other palm species. In fact I would call these “extended needles” as they are longer than any spine or thorn. You learn about spiny trunks in Peten, Alta Verapaz, or Izabal when you are hiking on a field trip and you slip in the muddy trail and your hand goes out automatically to grip a nearby tree to help you keep from falling: O U C H (actually the words that come out of your mouth are a lot more vulgar).

There is one thick vine along trails that we hiked every month through Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo areas of Peten that has long nail-sized spines: solid wood.

Tree Roots are worth photographing and studying

Ceiba pentandra have the most impressive buttress roots. But many other trees in the Municipio of Livingston have buttress roots. It would be helpful to have a 3-dimensional scanning system to map the roots of sample trees to show the world the size, shape, and length of these roots. The roots of mangrove trees are the most spectacular in the Municipio of Livingston.

The roots of strangler fig trees are the most amazing size and shape on the Island of Topoxte and other parts of Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo. I have also seen amazing strangler fig root systems in Alta Verapaz.

Palms are, technically (botanically) not trees

Botanists do not classify palms as trees, but most lists of Trees of Tikal or Trees of Wherever, do include all the tall palms. And also, these lists of trees tend to include all the xate palms, which are the size of bushes.

Corozo Palm trunks filled with ferns or Monstera vines in Aldea Plan Grande Tatin, Livingston.

When we are doing botanical field work in any area we make a list of all palm trees that earlier botanists or ecologists have found in this area. So for the Municipio de Livingston we have a list of 35 palm trees that should be present here. We have found about eight of these species so far, so a lot more field trips are needed.

- Tree flowers: lots of Pachira aquatica; lots of Pseudobombax ellipticum

Along the Canyon of Rio Dulce (between the east end of El Golfete and the town of Livingston) there are trees which I estimate are Pseudobombax ellipticum. They had few leaves and the flowers were so wilted I could not identify them for sure. Pachira aquatica trees are easily to identify from the leaves (I know this tree better because we have them growing, and flowering, in our Mayan Ethnobotanical Research Garden that surrounds our office in Zona 15, Guatemala City. So far all the Pseudobombax ellipticum trees are physically along the shore, often at the base of cliffs, along El Golfete area of Rio Dulce. In Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo we found Pseudobombax ellipticum trees not physically along the edge of rivers or humid areas. And most of the Pseudobombax ellipticum trees we have found elsewhere in Guatemala are at higher elevations.

A few balsa trees were spotted (Ochroma pyramidale) and of course some Ceiba pentandra trees. There should be a lot of molinillo trees in the Municipio of Livingston, but until we have found a plant scout (a local person that can work for us to find and identify trees) and until we have funds for his time and boat travel, we have not yet found any of potentially two species of Quararibea trees.

We have found and photographed a lot of Bernoullia flammea trees at Tikal, Yaxha, and near El Chal, Peten. There should be Bernoullia flammea in the Municipio of Livingston. If present they will be very noticeable when the trees are in full bloom.

Many trees have edible flowers

Yucca flowers are called izote. I raise them and eat them from my garden. Palo de pito flowers are edible. Madre de cacao flowers are edible. Would be helpful to make a list of every native tree of Guatemala which has edible flowers (and whether you need to cook them before you eat them).

- Tree Seed Pods

Some Inga trees have seed pods the length and width of a machete. Hymenaea courbaril pods are 70% shorter but comparable color (and so solid that you can’t easily open them, even with a machete (unless you hit them with full force swinging the machete from above down to the seed pod on the ground). We like to see, study, and photograph the seeds inside the pods, but that’s a challenge for seed pods as tough as guapinol pods, Hymenaea courbaril.

Photo by Nicholas with the iPhone Xs in Reserva Natural Tapón Creek, Área de uso múltiple Río Sarstún, Livingston, Izabal.

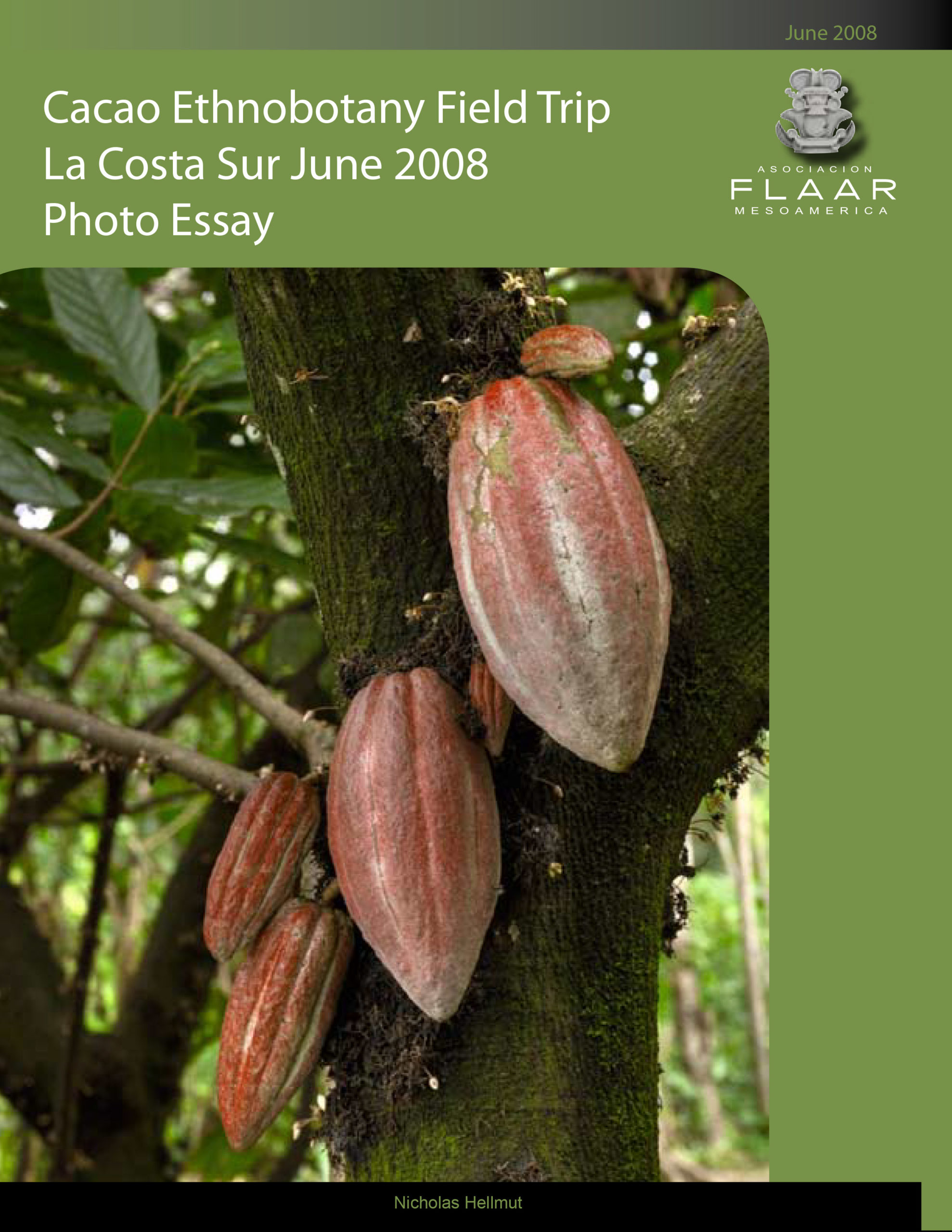

Tree Fruits

If you have a dozen fruit trees around your home you will get free healthy food for over a month from each tree (for decades). If a research institute were to show which trees fruit in which month, then local Maya, Xinca and Garifuna people could know what trees to plant so they have food literally fall from the trees every month all year. Many trees (such as zapote) fruit for more than one month.

So this is a project we definitely wish to undertake. Also important to list which vitamins, minerals and other nutritional aspects each fruit offers (and explain this in the local languages).

Fewer people in rural areas would die of Diabetes 2 if more fruit trees were around their homes (and if public education would explain what damage is caused by excess sugar (and other chemicals) in cheap junk food.

- Tree Seed Pods

Avocado flowers change sex depending on time of day. The pollinator of Ficus trees is a wasp with a fatal relationship with the flower. The yucca moth has an interesting relationship with the (edible) flowers of Yucca plants (the edible flowers are called Izote in Guatemala). We would love to do macro photography and do video of all the pollinators of Avocado, Ficus and Yucca.

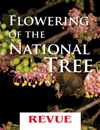

Would also like to do photography and video of mammals that pollinate: the micoleon in the flowers of the balsa tree. Bats pollinate the flowers of the national tree of Guatemala (Ceiba pentandra). For public education would be helpful to have close-up photos of all bees, beetles, butterflies, moths, bats, birds (lots more than hummingbirds) and other creatures that pollinate trees of Guatemala.

It is essential to protect all pollinators.

You can help protect fragile endangered ecosystems

The advantage of FLAAR (USA) and FLAAR Mesoamerica (Guatemala) is that we have experience in the Neotropical seasonal rain forests of Guatemala. We also do field work in the dry forest corridors parallel to Rio Motagua and parallel to Rio Sacapulas. But most of our decades of field work are in Peten and Alta Verapaz: and now Izabal (facing the Caribbean). Izabal is a literal paradise on earth for trees, vines, heliconia.

FrontDesk FLAAR.org reaches us (we assume you know how to turn this into an email address). FLAAR is tax exempt in USA; FLAAR Mesoamerica is a non-profit research and educational institute in Guatemala. What we need most are funds for a 4WD double cabin pickup (unfortunately a used one can’t survive on the roads where we work since there are no tow trucks or repair facilities out in the rain forests or deep into the mountains). Mazda, VW Amarok, Ford Ranger (Ford F250 not sold in Guatemala), or especially a Chevy Avalanche would be appreciated (best if bought locally in Guatemala so the local dealer will keep it maintained).

Our computers date back to a donation of years past: so need updated systems, and fresh new software. Dr Hellmuth lives off his retirement income as a former professor (so is not asking for money for himself); but funding would be appreciated for the university students who work for FLAAR Mesamerica: they are all capable, experienced, and motivated. And these funds are the equivalent of a scholarship for them to cover their university tuition and their living costs.

First posted March 20, 2020.